INTERVIEW WITH ABIBA COULIBALY

By Rebecka Öhrström Kann 25/06/2025

Abiba Coulibaly is a London-based film programmer whose projects are self-organized experiments in democratizing access to cinema. Her nomadic film club, Brixton Community Cinema, challenges the hierarchical structures of funding and operation normally in place in cinematic institutions through a collaborative, pay-what-you-can framework. Together with the architectural design collective bafalw, Coulibaly founded the film cooperative Atlas Cinema, operating in disused spaces as an incubator for moving image practices centring creative independence. We spoke about Coulibaly’s background in international development, her text Kinopolitics (2024) for Montez Press, and the need to invite a space for shelter and rest in her work.

Abiba Coulibaly is a London-based film programmer whose projects are self-organized experiments in democratizing access to cinema. Her nomadic film club, Brixton Community Cinema, challenges the hierarchical structures of funding and operation normally in place in cinematic institutions through a collaborative, pay-what-you-can framework. Together with the architectural design collective bafalw, Coulibaly founded the film cooperative Atlas Cinema, operating in disused spaces as an incubator for moving image practices centring creative independence. We spoke about Coulibaly’s background in international development, her text Kinopolitics (2024) for Montez Press, and the need to invite a space for shelter and rest in her work.

Rebecka Öhrström Kann: How did you become interested in film programming?

Abiba: I think I was always very interested in film growing up and from a young age, I felt really, really lucky to live in London. I have such a deep attachment and relationship with the city, and I just wanted to take advantage of everything that it offered me. While I was very into museums, I think I had such a visceral reaction to film and cinemas. That kind of emotional engagement, leaving us in tears or really angry or elated and laughing, was something that drew me to film.

I studied international development for my undergrad, so not film at all. But with international development there is this complex of humanitarian imagery that accompanies it, where every big charity will have their big fundraising campaign and use very specific imagery. So I was studying international development and thinking about this future in the “developing world” and these images of it produced by humanitarian organizations. And I think that made me watchful of the sort of imagery I was consuming. But I also found that films from these areasquestion those kinds of representations. When I graduated, I ended up working for the photojournalist agency Magnum. I think that when you do a degree like development studies, getting back into the arts can be a little bit tricky. Magnum was a great bridge from the geopolitics and the human rights stuff that I’d been studying, bridging it into photography and the moving image. They are primarily known for their photography, but they also have a significant film archive, which I started to play around with by putting on screenings.

But in terms of how I got to film programming, I found it extremely difficult to get a foot in. Part of the reason why I started Brixton Community Cinema was because there was no other forum in which I could put on a film. After job rejections and even rejections from unpaid schemes and programs, I was like, “Well, I guess if I want to do this, I have to do it myself.”

RÖK: That relationship to geography is really interesting.

AC: My degree was in geography which is about the whole world, right? Like where do our ideas come from, how are they shaped by spaces that we have been to? I know just from growing up in London, I had this immediate interest in places like outside of Europe, but if you don't have lived experience of that, then I think film is key to how we imagine and make our ideas about global geographies. I was using film as a way to kind of travel or better understand regions that I was interested in, but not able to physically visit. I also think it helped me build my interest in the otherization of certain geographies and spaces. Even just thinking about gentrification and how access is shaped by the infrastructure around you and things like the price of cinema tickets.

RÖK: You’ve collaborated with the architectural design collective bafalw on both Atlas Cinema and Views on the Atlantic. How did these collaborations come about?

AC: So I did an art program when I graduated. I kind of always wanted to do an art foundation, but didn't do an art foundation, and then I saw this three month program at School SOS. Just finding employment when I graduated was really really difficult, so I was like “I'll do this three month program.” The joke in my friendship group is that I did like every young person scheme in London [laughs]. I eventually did the Barbican Young Film Program, which is how I started Brixton Community Cinema after getting rejected from their first round, because I was like I can't even get onto the unpaid scheme. But one of the tutors from School SOS is a part of bafalw, and we had grown up and lived in the same area, so we’d often commuted to school together and we just kept in touch.

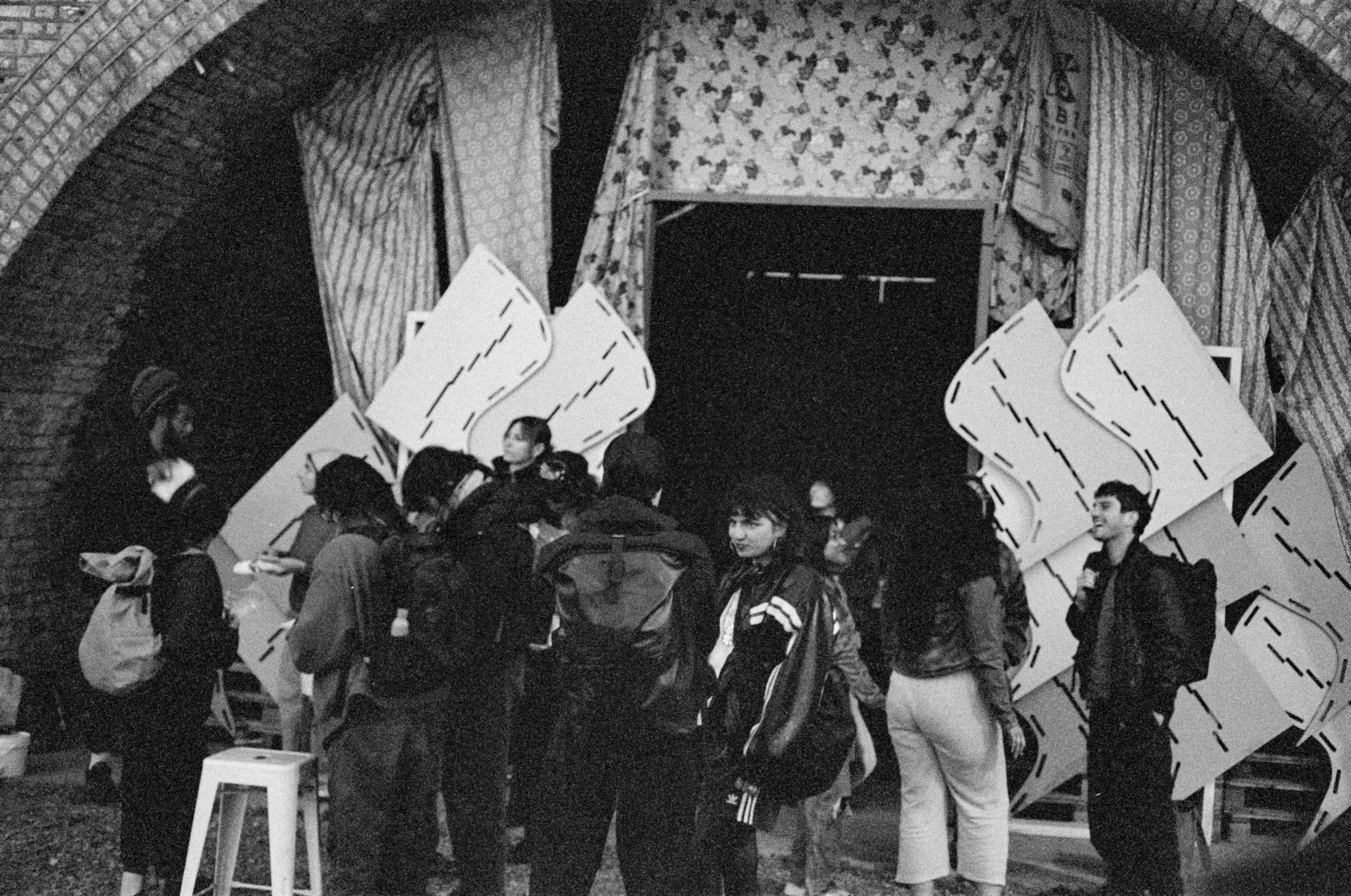

I think I asked them to design a poster for the first screening that I did with Brixton Community Cinema. Brixton Community Cinema, even now, pops up in various places, which sometimes is in response because I think a film will be received better in a different place, but sometimes because it’s just really hard to find a venue. I started out on Brixton Market, which was great, but you could only get like 20 people inside in that space. Once it got bigger and the audience got bigger, I had to find a different venue. I’m always changing it, which is sometimes fun and sometimes stressful. Eight months into the project, bafalw was like, “Brixton is going to be one of the critical areas in this year’s London Festival of Architecture. You're always moving about, why don't we just, like, build you a cinema space, and then you won't have to worry about the venue and the projector and all of that?” And I just laughed and said, “Yeah,” because it sounded like such a ludicrous idea. I’d just been running this film club for eight months and it was a very casual hobby, like once a month. So when they were like, “oh, we'll build you a cinema,” I was like whatever, and didn’t think much of it.

But luckily the project was chosen from the open call for the London Festival of Architecture, and we got funding, which made it possible. Because we had the space for a month, I wanted to maximize the use and decided we were going to do a film screening every single day. But I didn’t want to program it, so I decided to ask a different person or group to do a program every day. I think both because having just been doing it monthly, going into a 30 day straight program was quite an intense idea for me, but also because I feel really indebted to different film and non-film collectives whose events I've enjoyed over the years. This was a way to invite them back.

Then the next summer, when people said like “Are you going to do something similar?” I thought, I loved being able to work with so many people and say, “I really admire your work, come into the space and we can work together.” I wanted to do a project that allowed me to work with as many people as possible. Not just people who I was aware of and reached out to, but also people who I might not be aware of, but were interested in getting into film programming. But there was the issue of, how do we do this without funding? Because we were not going to get that funding again.

The Atlas Cinema arch is owned by a charity that takes care of and activates vacant spaces, which is how we're able to use it for free and work around the no funding issue. But it still means that there’s no money for upkeep or anything, and, because it’s a charity that manages the space for a fixed amount of time, we only have a short-term lease. But we had a base, and rather than contact people, I was open to anyone. People who had been getting in touch in the year between the projects and wanted to collaborate, but I wasn’t able to at the time, now had this space, so I kind of asked everyone who's interested in using it to let their friends know.

It just started as an empty spreadsheet, and then after a couple of days, I was like I don’t recognize half of these names [laughs]. I’m just glad that every single day, someone signed up to do something. Originally, it was just going to be Thursday to Sunday, because I still think it’s really hard to get people to come to events. Like if you put on something, especially if you don't have a large following and you're just starting out, it's really tricky. So, I was like, we can operate four days a week, but seven days is a bit ambitious. But this summer, it looks like it will actually be everyday, which is exciting.

RÖK: Obviously there is a tremendous amount of work that goes into this, as you have laid out, but I think it also shows how cinema can be such a simple thing when you break it down.

It just started as an empty spreadsheet, and then after a couple of days, I was like I don’t recognize half of these names [laughs]. I’m just glad that every single day, someone signed up to do something. Originally, it was just going to be Thursday to Sunday, because I still think it’s really hard to get people to come to events. Like if you put on something, especially if you don't have a large following and you're just starting out, it's really tricky. So, I was like, we can operate four days a week, but seven days is a bit ambitious. But this summer, it looks like it will actually be everyday, which is exciting.

RÖK: Obviously there is a tremendous amount of work that goes into this, as you have laid out, but I think it also shows how cinema can be such a simple thing when you break it down.

AC: Yeah, I think maybe it’s made to be more difficult than it needs to be. I have a big issue with things like just trying to contact a venue, and them being like, “maybe we can squeeze you in in, like, three and a half months,” and then you're working out the dates, and there’s so much back and forth. I wanted to try and streamline the process. And part of it means that the people doing the screening have to do the work of getting the film license, setting up the space, and doing the tech for themselves. But it is very much supposed to be like, “here’s a space, here’s equipment, just run with it.” I just want to make it an easier, less arduous experience for anyone who doesn’t necessarily even want to get into film programming, but just wants to experiment with it. People who can be put off by the barriers that there are to even like dipping their toe in. I don’t even have a pitching process. People are like “oh can I give you a pitch” and I'm like, it’s not about the pitch or whether or not I like it. As long as It's not like encouraging hate-crime, anything can go.

RÖK: You also write about film and last year you published Kinopolitics (2024) with Montez press, which is this lovely exploration of the relationship between the space and the screened image. I wondered if you could speak a little bit about the process of producing that piece and perhaps also how this aspect of your work feeds into your programming practice at large?

AC: I actually started writing because I wanted to program. I felt like everything I applied for I couldn’t get a place, so I applied for the BFI’s critics mentorship program in 2021, which happens every year as a part of the London Film Festival. I applied for that, and I was like it's not what I want to do, but it gives you free access to the whole festival, and it puts me in proximity to what I am interested in. So, that's kind of how I began writing and I find it’s actually more flexible and pays better than programming, but I don’t do it very often. When I was doing the mentorship with the BFI, it was partnered with Time Out and it was a very “five star, was this good or bad” way of writing, whereas I think I'm not interested in trying to assess whether a film was good or bad, or look at a five star system. It might just raise themes that I want to explore further or expand on. I mostly write about Francophone cinema because my dad is from Côte d’Ivoire, and I think that means I can add a certain context, a kind of bridge. So often, if I do pitch, it's because I think something is really, really interesting that hasn't been covered and I want to reflect on it a bit more myself, but I also want people to engage with it more. For Brixton Community Cinema, I’m actually more interested in commissioning other people to write. And with program notes, I would say the design by Em–Dash is just as important as the text, something that audiences can take home.

With Kinopolitics, I actually don't love it [laughs]. I found it really, really difficult to write, just because the prompt was a poem, and I'm not a big poetry person, so I think it was a very abstract prompt for me. I wanted to reflect on the London Festival of Architecture project, because it was really intense, every single day, for a whole month. Working in the street, I wasn’t just dealing with setting up the projector, making sure the guest curator was there and that the film file was working, but I was also just dealing with being in the busiest street in Brixton, and life in all its forms. Like, we were literally operating under the stairs that lead up to a train station, so you were just constantly hearing a train pull up and commuters come out. I just wanted to reflect on that experience, because if I'm trying to democratize access to cinema, what does it mean when you open something up so that anyone can come and wander into the screening at all times? I think with that project, me and bafalw really wanted to experiment with making art as accessible as possible at the end of the day, and the Kinopolitics piece was just reflecting on what that can look like in practice.

RÖK: The programming at Atlas Cinema goes beyond just film screenings to include workshops, talks, performances, music, and food. Could you talk about this decision to expand the programming beyond the image?

AC: It’s actually not really my choice. Personally, if I put on a screening for most part, the film is the focus. I also just really don’t like public speaking to be honest, so Q&A’s I kind of shy away from [laughs]. But, like you said, with a lot of the programming at Atlas there’s the film, but there is also food and talks. We had this event where the audience members basically became a choir at the end of screening, and next week someone’s coming in to do a live score. So, there are all these additional elements, and that’s not really my vision, but it’s just the nature of allowing people the space to do anything. Like, if we can just see a film, that’s great! But it’s about giving people the autonomy to do what they want in the space which is actually really, really rare to have a venue to do that. You’ve seen it, it’s not the most polished space in the world or super luxury or even comfortable, but it’s about giving autonomy for people to kind of imagine whatever program they want it to be. And I think that's where all of the additional things that are things that I wouldn’t necessarily do comes from, but it’s really about beyond myself because I am lucky enough to be able to do that separately. The variety comes through the world of people that stream through the space.

RÖK: The films shown at Brixton Community Cinema span genres, formats, and cultural contexts. How do you decide which films to include, and what drives these curatorial choices?

A: My approach has just been to reach out to people I admire. One great part of the program is that it’s a good excuse to be in touch with people like speakers or artists that I think are amazing. I think also as I grew up, I was just obsessed with everything that London had to offer, and through the Brixton Community Cinema I wanted to bring all of those quite varied things into one program.

For the Atlas Cinema programme, I think because I did the London Festival of Architecture project, it meant I still had people reaching out to me who were interested in programming. And rather than the people I looked up to who have shaped my experiences, it was now primarily people who were a generation younger than me, who were looking for a space and advice. And I've had so many negative experiences programming in institutions that I found it hard to recommend like, “oh you should work with X.” I think, especially in the past 18 months, I’ve just found myself quite disappointed with a lot of larger institutions. Like the Barbican has had multiple censoring of Palestinian artists and even with other cinemas that I’ve worked with, I just haven’t always had a great experience, things like that. With Brixton Community Cinema, I just don’t have the capacity to like say yes to every collaboration that comes my way. There were lots of people reaching out who had great ideas, but I just wasn’t sure where to direct them. Atlas partly meant that I could channel those people when I was like I think your proposal is great, I just don't quite know where to send you or what to respond back. I think in the end it’s about just giving people a start. Like, you don’t have to be super committed, but it’s just about being a space where people can try things out. I think having that opportunity to try in the first place is often the hardest, getting your foot in.

RÖK: A place to play and experiment is so important I think.

AC: Yeah! I’m I always like don’t worry if there are fuck ups or the quality is a little bit off, it really is supposed to be relaxed and wholesome. I also think I was conscious of the fact that I have lots of blindspots, as much as I think I view really widely. Again, Brixton Community Cinema being a place of me reaching out to who I like, but Atlas being this space where anyone can sign up and put their name down hopefully means that those blind spots that would occur because of me prioritising certain programming is no longer there. I also thought a lot about how to blur the line between the programmers and the audience. There are a lot of people who were audience members at Brixton Community Cinema who are now programming at Atlas, and it’s just through conversations with them after screenings and then it just stuck in my mind. When I got Atlas running, I was like they had a great idea or suggested something, let me reach out to them. I guess I just wanted cultural spaces to reflect the city, because we're so so so lucky to be in a city like London. I wanted the variety of films to be as reflective of the city as possible, that's my logic. And I guess it's mirrored in the name and my interest in geography, but it's my hope that the program truly reflects what it means.

RÖK: Atlas also puts on a lot of solidarity-driven fundraising through its screenings.

AC: Yeah, I think that’s something that depends a lot on who does the program. I have done fundraising before, but I think I still struggle with how cinema should and can respond to horrible horrible things that are happening in the world. After October 7, there have been several fundraisers at Atlas, but I haven’t put on any in that space. I’ve tried my best to amplify the people who do them, I just think that personally I struggle with what kinds of films do we show in response. Like, do we show one that’s reflective of what’s happening now, but then risk exposing the audience to really violent, victimizing imagery? I do think that the people who show this kind of stuff have the absolute best intentions, I think I just really struggle with that question. But the people who have done fundraisers have raised a lot of money which I’ve been really proud to see, because no one is making that much to pay themselves. It’s a small space, and the point is to provide affordable entrance. And people put so much work into their programs, even just the heavy lifting of having to carry out all the equipment themselves and set it up, and they’re not paying themselves necessarily. Often you are working towards a target, like a certain number of sales and to fill the cinema. But because Atlas operates without a profit, I think taking that imperative away changes how people program, and you can put on things that wouldn’t necessarily work in for-profit spaces. And they’ve also been incredibly successful, there are multiple programs which have raised over 500£ which is really amazing for a space that only holds 35 people.

RÖK: Atlas Cinema operates in a temporary physical space, and yet it feels deeply rooted in community. Do you think the audience can outlive the temporary setups?

AC: It’s always a struggle operating in temporary spaces and at the moment it looks like we might only have the Atlas space until June (At the time of interview in April 2025. Atlas Cinema had their last programming in the Loughborough Junction space on June 22, 2025). But at the same time, it does feel very lived in, the audience attachment really is there. And I think this is something that happens a lot with bafalw. I think we're all very aware of things like the housing crisis and access to shelter. So any time we are in a space, we want to facilitate film screenings, but we also just want to invite shelter. Because I think even in the city, like when you're walking around, finding something as simple as a public toilet or a bench is hard enough. So that is always at the forefront of our minds, and it’s also something I tried to reflect on in the Montez piece, because in both spaces that we’ve built, we’ve had unhoused people sleeping in them, and that’s just something that you have to navigate. Because even though it might not have been the purpose we set for the space, having a safe sleep is always going to be more important than a program. I think you can’t really get too precious about it when you’re confronted with much more pressing needs in the same space. It puts everything in perspective, I guess.

So I think, even though it’s temporary, the audience relationship has been built through the fact that people really are encouraged to go and stay. Like Atlas can almost be described as a semi outdoors bedroom because it is very cozy, and you do just end up just lounging about. There’s no imperative to leave because there is another screening that needs the space, so people do end up hanging out there, and if it’s a nice day, it opens up into the benches outside.

I do think the audience can outlive the space and I also can’t do what I do forever. Sometimes I get frustrated, because I don’t just do film in the evening, I’m also working in film during the daytime. I find myself quite frustrated with how a lot of things work in the industry in the UK at the moment, so I don’t tie myself to a particular project, but I 100% see the people programming in the space and their audience continuing elsewhere. Like this year, it’s about 60 people and groups programming, and last year there were about 35, and a lot of them have gone on to program at other places. Old Mountain Assembly is doing programming for Queercircle, and there is another group called Ifriqiya Cinema which did an event with the BFI this year. WAYWAAD collective started out at Atlas and they’re selling out the Ritzy cinema. I don’t think the goal is necessarily to go from Atlas to a larger institution that operates differently, but I do think that the goal is that these people end up being paid, which is why they are working with larger institutions that do have proper funding.

But like I said, I see Atlas as a space for experimentation, not perfection. I think with really interesting work, they are inevitably going to be successful. Atlas is a great incubator but then people can go on to do amazing things in other spaces. Knowing how many people use the space, not just people who put something on but also audience members, I think a part of it is just showing what you can do. Like, if you say that I'm going to turn this train arch into a cinema with no electricity and no running water it sounds so crazy, but you just need to see it to realize that it’s possible. So I do think that for everyone who's been here, either as an audience member or programmer, I'm really excited to see the things that they’re going to do.

RÖK: It really shows the potential of self-organized cinema I think, and how simple things can actually be, even though there is a lot of work behind it.

AC: Yeah, and I think that in the long run it’s not sustainable as an individual project. But you know that you're passing the baton on, like I know people who have started their own film clubs because of it. It’s a ripple effect, so I feel no upset or hopelessness if it does shut, because I know that people will continue doing other things as a result.

RÖK: Reflecting on a year of Atlas Cinema (at the time of the interview in April 2025), what have been the biggest challenges and rewards? How do you see it evolving, and what are you excited about for the upcoming season?

AC: I guess in terms of challenges there are ongoing low level ones, like how do you keep the space clean and comfortable? Just the issue of general maintenance, and the limits of how much you can maintain a space like that. And also for me, the admin input. It's supposed to be a hands-off project, because if I do things with Brixton Community Cinema, I have to physically be there and do a lot of film licensing, whereas Atlas Cinema is supposed to let me step back. But the reality is, just in terms of having like 85 events on this season, there is a lot of liaising with everyone and then just being like, “good luck” [laughs]. Like, I'm not going to be able to be there for each one, but I still need to organise a lot of the planning around dates and timing. We are doing inductions, so two days where you see how all the tech works and setting up. I think there’s that gap between it having to be low input, but also that it’s quite hard to step away. And part of it is practical, because you have to help people, but a part of it is because I have an attachment to it, and even if I tell myself, like, I'm going to step away.

I think for me, the big challenge looking back last year is also knowing what the space looked like before we started using it, compared to now. Knowing there's been so much work done for free, with absolute enthusiasm and love to change it and make it into something that is really welcoming and viable and has so much value to the user. Like, I'm not motivated by money, it's something that me and bafalw have built for free, and it's also not a particularly desirable space or anything. And seeing that even that is going to be taken away, I think it's so hard to have something long-term in this city. It's been reassessed by the council who wants to impose business tax on the space. But if this was imposed, the charity will have to give it up because it doesn't make them any money, so it would be too expensive to keep it. It’s like, if you build something up from scratch, market forces are still always going to scoop in and take it away. And I’m sure that it will have business tax and it will just go back to being unused. But this preference off—we’d rather make profit and pay to keep this space empty—while it could be slept in, or it could have films watched in it. Knowing how all consuming and predatory these forces are, I think that goes back to the geography aspect, the intensity in which land is commodified. That even spaces that have the bare minimum are things to be commodified. So I think I struggle with that, because for me it’s really important that the programs I’ve put on are really affordable. The only way that this kind of thing stays operating then is if you raise the ticket prices up to like 15 pounds, which then completely changes how many people come in and who comes, which I think is really important.

But in terms of what I’m looking forward to for the season, I’m just really, really looking forward to seeing people come back. I just have so much admiration for people who do the programming, and I’m really looking forward to seeing what they come up with and just enjoying the space as an audience member. And it’s not just because it’s my project, it’s because I know it’s genuine and there’s a whole new mix of people this year whose ideas I genuinly want to see in action. I also know what with bafalw, even though it’s quite tricky to operate this pay-what-you-can model in the UK and in London, I’m looking forward to seeing what we might be able to do in other locations. I guess I do really feel pushed out by London, but I’m very excited to see where else I could do this.