INTERVIEW WITH ABRAHAM CONE

By: Giselle Torres 30/12/2023

Giselle Torres: It would be great to hear about your journey in finding your practice and creative voice?

Abraham Cone: I got into art school because of my highschool art teachers, Geo Rutherford and Laura Naar. People mentoring me and taking me under their wing is what has cultivated my trajectory since then. Those sorts of relationships have been formative and expansive for my paintings—getting me to where I am now. Having people believe in you and see something in you that maybe you don’t see has been so treasured. Geo got me into printmaking and I made a portfolio of prints which carried me to SAIC.

I was homeschooled growing up; my mom was a teacher by profession so when she had me and my three brothers, she homeschooled us in a school of her own making. She couldn’t teach us everything so she took us to these homeschool co-ops which were run by all these catholic moms. They would educate us in areas of their respective expertise, and would supplement what other individual parents couldn’t teach at home.

I got into art from Mrs. Rowe, and “Gorgeous" Mrs. Campbell (she’d make all her students call her that, which I loved). I think I got a lot of access to things I couldn’t have experienced in public school. We were doing plasma cutting, by proxy, like first grade [laughs]. We would draw forms on steel and Mrs. Rowe’s husband who worked in metal fabrication would cut it out for us. I credit those classes as being very formative. It felt like such a powerful transformation to draw forms on steel and then a week later see it cut out, there’s something to that.

GT: Yeah, like having your ideas actualized is such a great and validating feeling.

AC: Yes, exactly!

Abraham Cone: I got into art school because of my highschool art teachers, Geo Rutherford and Laura Naar. People mentoring me and taking me under their wing is what has cultivated my trajectory since then. Those sorts of relationships have been formative and expansive for my paintings—getting me to where I am now. Having people believe in you and see something in you that maybe you don’t see has been so treasured. Geo got me into printmaking and I made a portfolio of prints which carried me to SAIC.

I was homeschooled growing up; my mom was a teacher by profession so when she had me and my three brothers, she homeschooled us in a school of her own making. She couldn’t teach us everything so she took us to these homeschool co-ops which were run by all these catholic moms. They would educate us in areas of their respective expertise, and would supplement what other individual parents couldn’t teach at home.

I got into art from Mrs. Rowe, and “Gorgeous" Mrs. Campbell (she’d make all her students call her that, which I loved). I think I got a lot of access to things I couldn’t have experienced in public school. We were doing plasma cutting, by proxy, like first grade [laughs]. We would draw forms on steel and Mrs. Rowe’s husband who worked in metal fabrication would cut it out for us. I credit those classes as being very formative. It felt like such a powerful transformation to draw forms on steel and then a week later see it cut out, there’s something to that.

GT: Yeah, like having your ideas actualized is such a great and validating feeling.

AC: Yes, exactly!

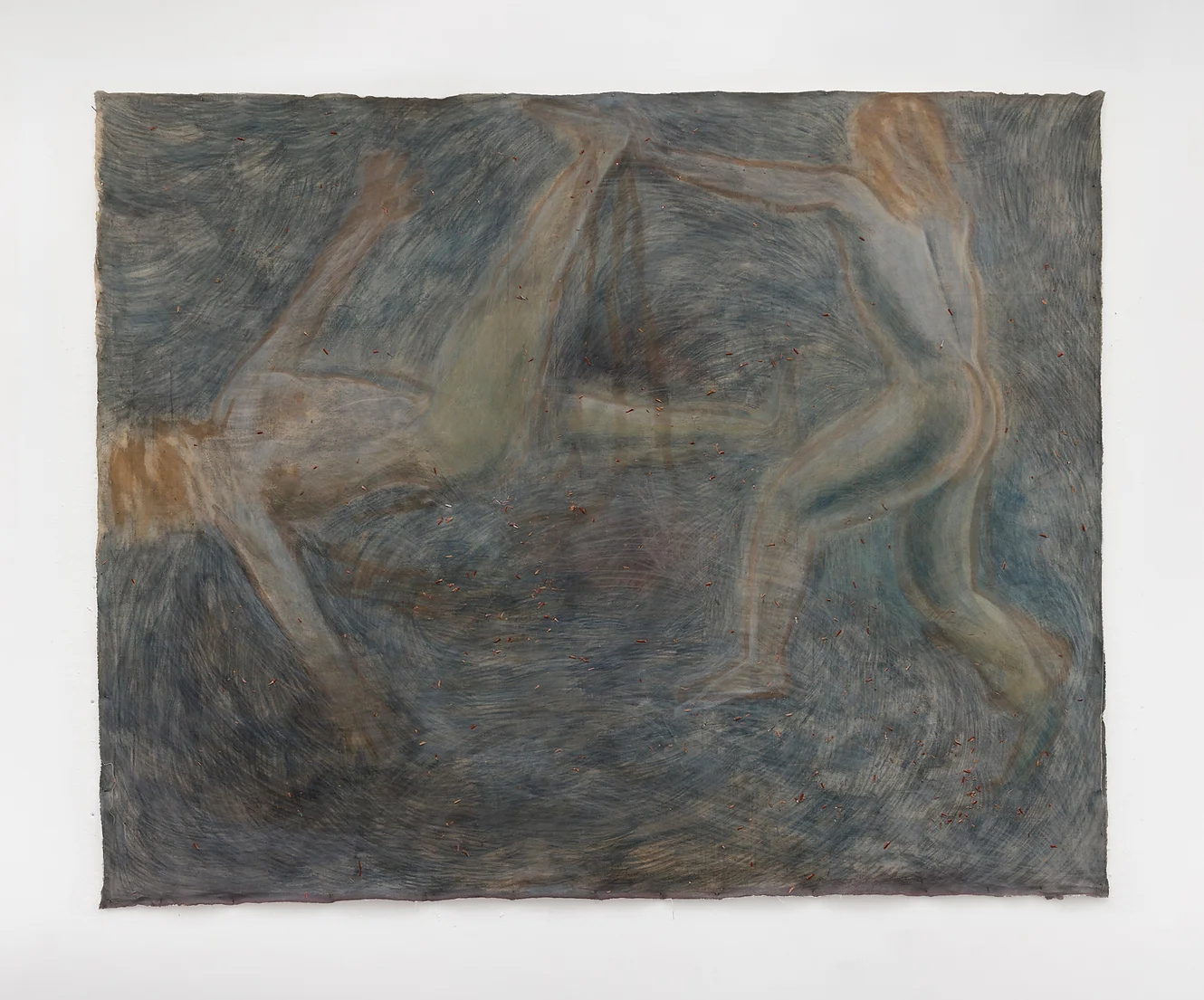

GT: When viewing your work, I am transported to this dream-like place. There are references to the human body, nature, and forms that bear similarities to our world but just feel a bit different. With that being said, how would you describe your work to someone who has not seen it before?

AC: Candida Alvarez came to my show in the summer of last year and she used this term, “vaporous” to describe the paintings. That has really stuck with me as a new critical term for the images—trying to create a vaporous atmosphere and space for the images. It also gets back to breath, wind, and airborne particulate matter. My work is also often pattern-based in that I am trying to compete with patterns.

GT: Yes, I can see that there is a uniformity in the work but then also this whisper of harmony disruption.

AC: Yeah, it allows for more variety. The human brain is a pattern-finding machine. It becomes more interesting when you try to break the pattern because your eyes kind of glaze over when you see a pattern. When that pattern is broken it triggers this close-looking that makes the image less processable. This tension compels the viewer to spend more time with the work because it is not perfectly uniform.

AC: Candida Alvarez came to my show in the summer of last year and she used this term, “vaporous” to describe the paintings. That has really stuck with me as a new critical term for the images—trying to create a vaporous atmosphere and space for the images. It also gets back to breath, wind, and airborne particulate matter. My work is also often pattern-based in that I am trying to compete with patterns.

GT: Yes, I can see that there is a uniformity in the work but then also this whisper of harmony disruption.

AC: Yeah, it allows for more variety. The human brain is a pattern-finding machine. It becomes more interesting when you try to break the pattern because your eyes kind of glaze over when you see a pattern. When that pattern is broken it triggers this close-looking that makes the image less processable. This tension compels the viewer to spend more time with the work because it is not perfectly uniform.

GT: It is wonderful that you are concerned not only about making the work but also about how you want your viewers to experience the work. Harmony is a comfortable atmosphere to fall into. When art is not easily readable or perfectly symmetrical, you have to do that extra work of holding your awareness and presence with the piece. Can you point us to a specific example of how you go about this in your practice?

AC: Yeah, and in that same sense, these crescents and oval shapes have been occurring in my practice. There’s this period of images that I’m interested in called Morrovian side-wound paintings. They are very small devotional paintings. They take as their subject the moment when Jesus was being crucified and the spear went into his side creating a side-wound.

The Moravians were an American religious sect, carrying around these images on their persons. The paintings have these oval shapes that open up into a landscape so basically it’s a landscape revealed in a body with figures inside. There is this idea of being held inside of somebody; naturally the images are mildly homoerotic. I’ve been returning to the interconnection of the hide or skin of a body and the hide or skin of a landscape. “Hide” used to be a unit of land measurement, after all. So there’s this poetic interconnection between pictorial space and real space that I’m interested in.

AC: Yeah, and in that same sense, these crescents and oval shapes have been occurring in my practice. There’s this period of images that I’m interested in called Morrovian side-wound paintings. They are very small devotional paintings. They take as their subject the moment when Jesus was being crucified and the spear went into his side creating a side-wound.

The Moravians were an American religious sect, carrying around these images on their persons. The paintings have these oval shapes that open up into a landscape so basically it’s a landscape revealed in a body with figures inside. There is this idea of being held inside of somebody; naturally the images are mildly homoerotic. I’ve been returning to the interconnection of the hide or skin of a body and the hide or skin of a landscape. “Hide” used to be a unit of land measurement, after all. So there’s this poetic interconnection between pictorial space and real space that I’m interested in.

GT: Can you describe one of the moments you knew you wanted to pursue painting and printmaking solely? Did you dabble in other mediums before and if so, why is it about these two practices that calls to you more?

AC: Oh yeah, print is an older medium for me that I feel I orbit. Print was actually how I got into image making. Geo, my art teacher in high school used to drive me to Eastern Michigan University [where she studied printmaking] to use their printing presses each time I finished a matrix—when the doors were locked she’d have me climb through the window to unlock the studio. Since then, my paintings have always had aspects of print in them, be that color separations, structure, or repeating forms. So, even when I’m painting it still comes back to print a bit.

AC: Oh yeah, print is an older medium for me that I feel I orbit. Print was actually how I got into image making. Geo, my art teacher in high school used to drive me to Eastern Michigan University [where she studied printmaking] to use their printing presses each time I finished a matrix—when the doors were locked she’d have me climb through the window to unlock the studio. Since then, my paintings have always had aspects of print in them, be that color separations, structure, or repeating forms. So, even when I’m painting it still comes back to print a bit.

I had a meandering route to painting. I started college focusing on printmaking and then went into sculpture, where I stayed for awhile and I thought that was what I wanted to do. Then, I changed course again into arts administration because I thought I wanted to be a curator. Then I landed in painting the last two semesters of school and that’s kind of been where I’ve stayed. All of these stops along the way have impacted my paintings. Elements of these different disciplines are present in my paintings and that’s something that I like about them. In terms of found-objects and materials, how I think about material usage in the images, that’s actually a spacial, and time-based concern, which comes from sculpture— seeing what I can source and what I can find and letting images unfold from there.

Like this magenta here is an ink from pokeberries, and that brown is walnut ink that I made from fermented walnuts. You extract tannins from their hulls and you get this really dark color with a long history. And this watercolor I got from one of my friends. The colored pencil I went over with on top is from the Chicago Creative Reuse Exchange—they are an organization that works to divert materials from waste sheds. You can volunteer in their warehouse for three hours, and, in exchange, fill a box with art supplies. So, image-making becomes relational by way of the transformation of time into art materials, and how that lingers in the work. The different ways in which the materials come to the painting stay with the painting, or that’s what I hope at least.

GT: You have made this one piece called Untitled from 2022 and the work takes on such a hide-like quality and throughout this conversation I keep returning to it in my mind as we chat about ideas and processes. There is a very intriguing way in which you treat the materials. You use uncommon materials to create what appears to be scarred and alive at the same time. Can you walk us through the process of bringing this piece to life? Your treatment of materials is so fascinating and you carry through into all your works in different ways.

AC: Earlier I mentioned my trajectories and stops along the way; I’ve been trying to think about pictorial space, the picture-plane, and painting as a curatorial space where I can put elements together that I want to be in conversation with each other.

After graduating, I worked as a gold leaf gilder for frames and furniture—working with techniques that span back into antiquity. That craft uses animal hide glues in every step of fabrication because the material is archival and reversible. In water it will dissolve and once dry it will last for eons. The wood is soaked in hide glue and then the gesso is applied, which is hide glue and calcium carbonate, and then a material called bole is applied, which is hide glue and clay.

I was using hide glue a lot at work and started thinking about how it is a material with a rich painterly history. It is a traditional sizing for canvas to protect the weave from the caustic elements of oil paint. So it has this long history of being the first layer applied to the canvas, yet now collagen and cartilage materially is primarily a waste bi-product. This connective tissue is useful in painting, so that’s how I think about it ethically, this idea that using the collagen and cartilage for a specific purpose is tenable because it would have just been discarded anyway. Working this way also lets me avoid plastics from PVA sizings.

After graduating, I worked as a gold leaf gilder for frames and furniture—working with techniques that span back into antiquity. That craft uses animal hide glues in every step of fabrication because the material is archival and reversible. In water it will dissolve and once dry it will last for eons. The wood is soaked in hide glue and then the gesso is applied, which is hide glue and calcium carbonate, and then a material called bole is applied, which is hide glue and clay.

I was using hide glue a lot at work and started thinking about how it is a material with a rich painterly history. It is a traditional sizing for canvas to protect the weave from the caustic elements of oil paint. So it has this long history of being the first layer applied to the canvas, yet now collagen and cartilage materially is primarily a waste bi-product. This connective tissue is useful in painting, so that’s how I think about it ethically, this idea that using the collagen and cartilage for a specific purpose is tenable because it would have just been discarded anyway. Working this way also lets me avoid plastics from PVA sizings.

Also, I think about connective tissue metaphorically. Wind is a connective tissue in a way that connects continents. Minerals from the Sahara Desert gust across the Atlantic Ocean and into the Amazon. Or when you’re speaking across space or singing, it is a connective tissue between people. So, there’s a metaphor for connection in the way I am joining elements together on the picture plane—or even in the relationship of the materials. I will pair a material that was gifted to me with another that I found. It creates this firmament of an image.

GT: Our conversation makes me really sit with the characteristics of wind and how it can come from our lungs but then it surrounds us and holds us. What made you begin thinking critically about wind?

AC: Yeah, totally! Wind has mythological and spiritual coding. You know, “winds of change” or the idea of wind blowing you into somewhere new or something coming to you in the wind. This is something I’m trying to piece together in the work. My father taught me to see thermals by watching hawks circle rising air currents. He was a glider-pilot instructor growing up, and would drift over our home in rural Michigan, dropping items for my brothers and me to find in long grass. Wind is often mythologized as a paternalistic force, baring aloft seeds, spores, and minerals—and, my biblical namesake Abraham is the “Father of Many”—so there’s this sort of procreative prophecy wrought into my name, even though I can’t/won’t have children biologically. For me, wind marks passage from one thing into another.

GT: So, in terms of themes and metaphors, you mention the consistent presence of wind in your work. Is there a common concept or idea that you intentionally make present in your compositions at the moment?

AC: Back in college and even after college I was really concerned with making a good painting. I was always editing and refining what I was executing. In terms of a common thread I make a lot of the same image. Like here is a print I made which is a choir singing and you can see I made another one here. So, I work with the same subjects a lot but the unifying thread now is that I have just stopped trying to make good paintings, and have just started making things that I want to make, and the images I want to see. By letting that be the driving force of the work, there are natural overlaps that occur because if I am being true to myself, there will obviously be interconnections. Letting the work come first and then those threads reveal themselves afterwards when I am not trying to force them beforehand.

People have given me pushback and have said “Oh, it doesn't make sense for you to be making this painting because it’s not like any of your other works” but then if you wait six months, it makes sense. The reason is there but sometimes you just might not know; as long as you're working from the right place and following your desires, you can’t make anything outside of your practice. That’s something one of my former professors, Alex Chitty said, which I love because it is so permission-giving. I’ve felt pressure to diminish myself, make myself smaller, for a while I tried to get myself completely out of the paintings to the point of hard edge abstraction. At the end, there is no spirit in those paintings or touch or humanness. Like what’s the point of painting if that’s not there?

GT: Based on your process of making multiple renditions of one idea demonstrates your dedication to finding yourself in the composition more and more with each version. As for the first variation of certain compositions, what advantages come with having multiples for you? Would you display them in a show and hold them to the same level of readiness to be seen as the final version?

AC: Yeah, I’d say that comes back to printmaking with having multiples of the same image. The image moves across media. Like you can have an image that’s a photograph and then the same image that’s a drawing and another that is a painting and then another that’s a print. All the media specificities bring different content to the image. A photo reads differently than a watercolor because those have very different histories tied to them. And trying to work with those histories like the history of picturesque watercolor landscape painting is something I have been thinking a lot about with my paintings lately. There’s this way we’ve come to view, in an American context, places and people in the world through these different media. Plein air watercolor painting was a media that contributed to producing what we recognize as landscape. Watercolor as a media was historically coded to be effeminate—I’ve been thinking about watercolor in conversation with queerness and gender-identity. When a watercolor functions at the scale of a history painting it subsumes a viewer's whole field of vision, which is something I’m interested in.

AC: Back in college and even after college I was really concerned with making a good painting. I was always editing and refining what I was executing. In terms of a common thread I make a lot of the same image. Like here is a print I made which is a choir singing and you can see I made another one here. So, I work with the same subjects a lot but the unifying thread now is that I have just stopped trying to make good paintings, and have just started making things that I want to make, and the images I want to see. By letting that be the driving force of the work, there are natural overlaps that occur because if I am being true to myself, there will obviously be interconnections. Letting the work come first and then those threads reveal themselves afterwards when I am not trying to force them beforehand.

People have given me pushback and have said “Oh, it doesn't make sense for you to be making this painting because it’s not like any of your other works” but then if you wait six months, it makes sense. The reason is there but sometimes you just might not know; as long as you're working from the right place and following your desires, you can’t make anything outside of your practice. That’s something one of my former professors, Alex Chitty said, which I love because it is so permission-giving. I’ve felt pressure to diminish myself, make myself smaller, for a while I tried to get myself completely out of the paintings to the point of hard edge abstraction. At the end, there is no spirit in those paintings or touch or humanness. Like what’s the point of painting if that’s not there?

GT: Based on your process of making multiple renditions of one idea demonstrates your dedication to finding yourself in the composition more and more with each version. As for the first variation of certain compositions, what advantages come with having multiples for you? Would you display them in a show and hold them to the same level of readiness to be seen as the final version?

AC: Yeah, I’d say that comes back to printmaking with having multiples of the same image. The image moves across media. Like you can have an image that’s a photograph and then the same image that’s a drawing and another that is a painting and then another that’s a print. All the media specificities bring different content to the image. A photo reads differently than a watercolor because those have very different histories tied to them. And trying to work with those histories like the history of picturesque watercolor landscape painting is something I have been thinking a lot about with my paintings lately. There’s this way we’ve come to view, in an American context, places and people in the world through these different media. Plein air watercolor painting was a media that contributed to producing what we recognize as landscape. Watercolor as a media was historically coded to be effeminate—I’ve been thinking about watercolor in conversation with queerness and gender-identity. When a watercolor functions at the scale of a history painting it subsumes a viewer's whole field of vision, which is something I’m interested in.

GT: Throughout your whole ideation and process you are so thoughtful and the fact that you do so much research and immerse yourself in these rich histories is wonderful. Do you have a current art movement or medium you are in the midst of uncovering truths about?

AC: Oh, papermaking. I’ve been getting into papermaking lately and I’ve been gathering plant material wherever I can find it. And I’m going to my first caustic boil this week hopefully! That’s where you submerge gathered plant fibers in a boiling soda-ash bath, and the soda-ash dissolves all the waxes and lignins and different chemical compounds in the plants that would deteriorate the paper over time, leaving you with just the cellulose. So, yeah I’ve been reintroduced to papermaking through two of my friends who together run Switchgrass Paper. They’re working to create more space for papermaking in Chicago; I took one of her workshops and I got really jazzed up about printmaking. Now, I’ve been doing research on my own. Before I was papermaking with plants, I was working on found papers, or papers that were given to me, like this paper behind you. My Madeleine Leplae hosted this drawing event and gave everyone these notebooks so I tiled the pieces of paper together to make a larger piece of paper using hide glue, on which I’ve now been oil painting. So, image-making is relational, from her giving me the notebook and then trying to put that into the work.

GT: Yeah, and I love the aged-look that the paper has taken on and that all the edges are near seamless and it seems like each page has it’s own personality. Was that intentional?

AC: No, that was an accident [Laughs]. Basically, the hide glue kind of heaves even after it dries, so it swells and shrinks with temperature and humidity. I can actually show you on this larger piece. So, this one I had to re-stretch because it was one-size and then it completely shrunk because of the humidity. The paper becomes responsive to the environment so it continues this idea of it being alive or of body. Even when you’re reconstituting the glue, you have to heat it to body temperature because that will melt the crystals. If you heat it above that, the proteins in the glue will just break down and you won’t have any structural integrity to the glue. So, it definitely retains this idea of being of body by remaining responsive to the environment, which I think becomes part of the work.

Maybe that goes back to gold leaf gilding too; there’s this sense that you ingest the materials or the materials enter you or something. There’s one technique I learned to fix cracks in frames where you form a ball of hide glue and calcium carbonate [which is basically just chalk] and then you put the mass into your mouth. The ball stays in your lip and coagulates with your saliva, which then you express to balm the cracks. The saliva helps the gesso not be so brittle. It’s funny because the sleekest and most modern frames actually have a human and animal body in them. Those types of frames are trying to get the craftsperson’s hand completely out of them, yet actually so much body is needed in the work. Likewise, you ingest the materials and they become part of your being.

AC: Oh, papermaking. I’ve been getting into papermaking lately and I’ve been gathering plant material wherever I can find it. And I’m going to my first caustic boil this week hopefully! That’s where you submerge gathered plant fibers in a boiling soda-ash bath, and the soda-ash dissolves all the waxes and lignins and different chemical compounds in the plants that would deteriorate the paper over time, leaving you with just the cellulose. So, yeah I’ve been reintroduced to papermaking through two of my friends who together run Switchgrass Paper. They’re working to create more space for papermaking in Chicago; I took one of her workshops and I got really jazzed up about printmaking. Now, I’ve been doing research on my own. Before I was papermaking with plants, I was working on found papers, or papers that were given to me, like this paper behind you. My Madeleine Leplae hosted this drawing event and gave everyone these notebooks so I tiled the pieces of paper together to make a larger piece of paper using hide glue, on which I’ve now been oil painting. So, image-making is relational, from her giving me the notebook and then trying to put that into the work.

GT: Yeah, and I love the aged-look that the paper has taken on and that all the edges are near seamless and it seems like each page has it’s own personality. Was that intentional?

AC: No, that was an accident [Laughs]. Basically, the hide glue kind of heaves even after it dries, so it swells and shrinks with temperature and humidity. I can actually show you on this larger piece. So, this one I had to re-stretch because it was one-size and then it completely shrunk because of the humidity. The paper becomes responsive to the environment so it continues this idea of it being alive or of body. Even when you’re reconstituting the glue, you have to heat it to body temperature because that will melt the crystals. If you heat it above that, the proteins in the glue will just break down and you won’t have any structural integrity to the glue. So, it definitely retains this idea of being of body by remaining responsive to the environment, which I think becomes part of the work.

Maybe that goes back to gold leaf gilding too; there’s this sense that you ingest the materials or the materials enter you or something. There’s one technique I learned to fix cracks in frames where you form a ball of hide glue and calcium carbonate [which is basically just chalk] and then you put the mass into your mouth. The ball stays in your lip and coagulates with your saliva, which then you express to balm the cracks. The saliva helps the gesso not be so brittle. It’s funny because the sleekest and most modern frames actually have a human and animal body in them. Those types of frames are trying to get the craftsperson’s hand completely out of them, yet actually so much body is needed in the work. Likewise, you ingest the materials and they become part of your being.

GT: That is so beautiful. When I think of the word, “heaving” I immediately think of someone who just went on a run and their chest rising and falling to gather air. For a painting to have that ability is something very special because it is independent of itself in a way. Did you foresee this happening and wanted to experiment with it? Do you leave a door open for those possibilities to arise and welcome the surprises?

AC: Working with the material, it’s just been something I’ve had to contend with. Sometimes it’s a bit problematic because if the humidity or temperature changes, and you have already stretched the canvas at one temperature and humidity and if you bring it somewhere else then the glue changes and the canvas will get loose and buckle. So, when you're working with stretched canvas it is a bit of a challenge but that is also a reason I like working with it. I’ve started seeing it as a positive or conceptual aspect of the paintings.

The paintings are about natural force. Whether that be of wind or spring water coming up from a spring-fed lake, or erosion or people moving across the canvas even. There’s something about movement and temperature. So the paintings are about natural forces and how the

AC: Working with the material, it’s just been something I’ve had to contend with. Sometimes it’s a bit problematic because if the humidity or temperature changes, and you have already stretched the canvas at one temperature and humidity and if you bring it somewhere else then the glue changes and the canvas will get loose and buckle. So, when you're working with stretched canvas it is a bit of a challenge but that is also a reason I like working with it. I’ve started seeing it as a positive or conceptual aspect of the paintings.

The paintings are about natural force. Whether that be of wind or spring water coming up from a spring-fed lake, or erosion or people moving across the canvas even. There’s something about movement and temperature. So the paintings are about natural forces and how the

paintings react to natural forces of the world.

GT: You seem to have this duty to use what you have and are conscious not to over consume and to be resourceful in finding materials. What motivates you to go about gathering materials in this way?

AC: Yeah, totally. It's more about a principle that I follow that is more of a way of being or of trying to find a way of inhabiting the world through image-making. Painting is a way for me to find a new way of being in the world. And I see painting as a kind of laboratory or place to explore where I can paint myself into a new way of being or into a new relationship with the people around me or the place I am. It’s not necessarily a benevolent thing—it’s not that I’m trying to be a good person, I’m actually skeptical of people who view themselves as such. It’s more that I can’t not do that, or that it's too despairing to inhabit the world in any other way at this moment—that’s what it feels like at least. These past several years I’ve had to discern what is actually precious to me; working from those moments and items feels like an upwelling that I just need to put in the painting. I’m at a point where I’m so bored with acrylic painting or colors that are made in laboratories or color that has lost its body, so to speak. You can make an image but what is the material, because oftentimes the material is the meaning. So, acrylic paint is just plastic mixed in a binder and the artist will wash their brushes in the sink, and the microplastics enter our waterways. I got to a point where I couldn't help but see that eventuality as part of the work—that becomes as much a part of the work as what is depicted, in my view.

GT: You seem to have this duty to use what you have and are conscious not to over consume and to be resourceful in finding materials. What motivates you to go about gathering materials in this way?

AC: Yeah, totally. It's more about a principle that I follow that is more of a way of being or of trying to find a way of inhabiting the world through image-making. Painting is a way for me to find a new way of being in the world. And I see painting as a kind of laboratory or place to explore where I can paint myself into a new way of being or into a new relationship with the people around me or the place I am. It’s not necessarily a benevolent thing—it’s not that I’m trying to be a good person, I’m actually skeptical of people who view themselves as such. It’s more that I can’t not do that, or that it's too despairing to inhabit the world in any other way at this moment—that’s what it feels like at least. These past several years I’ve had to discern what is actually precious to me; working from those moments and items feels like an upwelling that I just need to put in the painting. I’m at a point where I’m so bored with acrylic painting or colors that are made in laboratories or color that has lost its body, so to speak. You can make an image but what is the material, because oftentimes the material is the meaning. So, acrylic paint is just plastic mixed in a binder and the artist will wash their brushes in the sink, and the microplastics enter our waterways. I got to a point where I couldn't help but see that eventuality as part of the work—that becomes as much a part of the work as what is depicted, in my view.

I started moving into a new way of working by having a set quantity of materials and letting the painting unfold from there—seeing what would come. I still buy things when I need them but putting them in conversation with other materials is important to my practice because in this historical present with wildfires and climate change and pandemics there are all these huge overarching catastrophes; it’s not that I feel I am contributing to or helping the world necessarily, but the gesture of trying to equalize is in the painting, and maybe that can emanate from the work. Working that way, I hope the painting becomes more than the sum of its parts. What is bound up in the materials becomes the force of the painting, and that kind of transcends the virtuosity of how the paint was technically applied.

GT: I feel that it is all about intention and for example you have gathered pokeberries and plant materials and created a reciprocal relationship with the plants that produced them that you repaid with gratitude. I’m reading Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer right now and she talks a lot about the unspoken language between curious creators and nature. Would you say that this is something you resonate with?

AC: Oh yeah, and even Robin Wall Kimmerer talks about the gift economy, you know, seeing the world as a gift, which then necessitates a return of the gift; the gift must move, afterall. And, even the transcendentalist writer Annie Dillard used to “hide a pretty penny” for someone else to happen upon, knowing in her heart that she made somebody's day when she was a little girl. She writes in Pilgram at Tinker Creek about how if you can cultivate a healthy simplicity to the point where just happening upon a penny can make your day, then you’ll have a life full of good days because the world is strewn and studded with pennies. So, thinking about that, I hope my paintings aren’t grandiose, even if they are large; I get excited about something like this, a piece of charcoal my friend Christine gave me, which she made in her dutch oven over embers with gathered twigs. I’ve been drawing sparingly with this one piece that she gave me a year or so ago.

GT: You seem very sentimental and that sentimentality seems so present in your work.

AC: One of my dear friends, Dominique Knowles, who is a painter, said this one thing I have kept with me. To paraphrase, he said, “sentimentality and intimacy used to be seen as kitsch—and now that the personal is so political, sentimentality and intimacy are avant garde.” In other words, it’s a radical gesture to value vulnerability and intimacy in our historical present. Working from that place, there is more at stake for me in the paintings, which is sort of my contract with the viewer. If you omit all human touch from the paintings what is the point of making them in the first place? My stakes for what I see as good painting have changed over the years—now I see desire as reason enough to make a painting.

GT: Yes, I definitely agree with you. Also, art lends itself to be such a great tool in expressing our emotions or processing events or feelings that are happening to us and to not tap into that is a missed opportunity to explore and play with.

AC: Exactly! That’s what art can do. I think sometimes people expect artwork to do too much or they think their artwork is going to fix all these things and maybe it might be more effective for them to write an essay or start a petition. One thing I think art can do is reveal things that are aspirational that you want to happen. Basically if I can act out in my paintings a way of being for myself then maybe painting can become prophetic—and, through the painting a transformation can occur that brings me somewhere else in the real world. This way, painting becomes an instrument for transformation: both action into material and material into action.

GT: I definitely agree that for a work that is attempting to have an immense impact it should encourage people to think critically and empathetically but that isn’t an easy feat. And in terms of abstract art, when there are no hyper realistic representations of particular ideas and content, how do you hope your viewers extract meaning from your work?

AC: I’d say I want my viewers to feel subsumed by the paintings. I paint this large because I want the viewer to have a physical relationship with the paintings, not just optical, even though the images take up your whole field of vision. I want people to have an encounter with the materials of the painting, like here, this light brown is made from a sandstone from Michigan I gleaned off the ground, which is one of the bedrocks where I live. So, creating an encounter is one thing I’m after.

I ended college right when the pandemic started and during the pandemic I was in my room a lot more which was very small. I felt so faced with this room that I was stuck in because I was quarantined from my roommates at that time; painting became a way for me to transform my space and create what I wanted to see and that evolved into making more paintings. My paintings used to be a bit wry or ironic; I was trying to be smart and clever within the works or something, and once the pandemic hit, that all left my practice. I just didn't care about that at all, and that tone wasn't meaningful to me. So, I had this realization that image-making can transform a space, and that I can lay before my eyes what I want to see. I want people to feel movement and gentle force and maybe even more alive and noticing themselves.

AC: Oh yeah, and even Robin Wall Kimmerer talks about the gift economy, you know, seeing the world as a gift, which then necessitates a return of the gift; the gift must move, afterall. And, even the transcendentalist writer Annie Dillard used to “hide a pretty penny” for someone else to happen upon, knowing in her heart that she made somebody's day when she was a little girl. She writes in Pilgram at Tinker Creek about how if you can cultivate a healthy simplicity to the point where just happening upon a penny can make your day, then you’ll have a life full of good days because the world is strewn and studded with pennies. So, thinking about that, I hope my paintings aren’t grandiose, even if they are large; I get excited about something like this, a piece of charcoal my friend Christine gave me, which she made in her dutch oven over embers with gathered twigs. I’ve been drawing sparingly with this one piece that she gave me a year or so ago.

GT: You seem very sentimental and that sentimentality seems so present in your work.

AC: One of my dear friends, Dominique Knowles, who is a painter, said this one thing I have kept with me. To paraphrase, he said, “sentimentality and intimacy used to be seen as kitsch—and now that the personal is so political, sentimentality and intimacy are avant garde.” In other words, it’s a radical gesture to value vulnerability and intimacy in our historical present. Working from that place, there is more at stake for me in the paintings, which is sort of my contract with the viewer. If you omit all human touch from the paintings what is the point of making them in the first place? My stakes for what I see as good painting have changed over the years—now I see desire as reason enough to make a painting.

GT: Yes, I definitely agree with you. Also, art lends itself to be such a great tool in expressing our emotions or processing events or feelings that are happening to us and to not tap into that is a missed opportunity to explore and play with.

AC: Exactly! That’s what art can do. I think sometimes people expect artwork to do too much or they think their artwork is going to fix all these things and maybe it might be more effective for them to write an essay or start a petition. One thing I think art can do is reveal things that are aspirational that you want to happen. Basically if I can act out in my paintings a way of being for myself then maybe painting can become prophetic—and, through the painting a transformation can occur that brings me somewhere else in the real world. This way, painting becomes an instrument for transformation: both action into material and material into action.

GT: I definitely agree that for a work that is attempting to have an immense impact it should encourage people to think critically and empathetically but that isn’t an easy feat. And in terms of abstract art, when there are no hyper realistic representations of particular ideas and content, how do you hope your viewers extract meaning from your work?

AC: I’d say I want my viewers to feel subsumed by the paintings. I paint this large because I want the viewer to have a physical relationship with the paintings, not just optical, even though the images take up your whole field of vision. I want people to have an encounter with the materials of the painting, like here, this light brown is made from a sandstone from Michigan I gleaned off the ground, which is one of the bedrocks where I live. So, creating an encounter is one thing I’m after.

I ended college right when the pandemic started and during the pandemic I was in my room a lot more which was very small. I felt so faced with this room that I was stuck in because I was quarantined from my roommates at that time; painting became a way for me to transform my space and create what I wanted to see and that evolved into making more paintings. My paintings used to be a bit wry or ironic; I was trying to be smart and clever within the works or something, and once the pandemic hit, that all left my practice. I just didn't care about that at all, and that tone wasn't meaningful to me. So, I had this realization that image-making can transform a space, and that I can lay before my eyes what I want to see. I want people to feel movement and gentle force and maybe even more alive and noticing themselves.

GT: This is my first time visiting your studio and when I first walked in I was confronted by large paintings and it would not have been possible for me to not address them and have a response to them because they were demanding attention and contemplation from me. At the same time, the size of your paintings fluctuates. What role does size play in your practice? How do you go about envisioning how your paintings will live on a wall?

AC: When the paintings are flush to the wall, they become part of the room, indeed, they’re adhered directly to the drywall. I want the paintings to recede into the room. I am not so into paintings that beat you over the head. I want my paintings to have a soft power and I feel that my role as the artist is to make that atmosphere in the painting. When the painting is finished it creates an atmosphere in the room. Painters often try to do this thing where the painting is the focal point of the room and I’m a bit skeptical of that. Like, what’s the point of that besides stroking your own ego? And, often the resulting work lacks subtlety. Like a painting can recede and be a part of the room. People have said that my paintings are a bit like wallpaper and I see no problem with that interpretation, even if I don’t necessarily agree. I want my viewers to feel like the work is a balm. I want my paintings to be a site for reunification. That is something I think painting can do is be a unifying force for parts of yourself, or with the world, or with relationships. Some artists want their paintings to induce fear and I just want my paintings to sing to me [laughs].

GT: There is such a tenderness that you seem to treat your materials with from your approach to brushstrokes and use of color that bear both levity and heavy undertones and they feel as though they are whispering in a sense. How do you go about choosing what colors or textures from piece to piece?

AC: Some of it is happenstance like we’ve talked about but the other aspect goes back to color relationships. It’s not that I believe that certain colors can elicit emotions, it's more that I think color relationships can elicit emotions. So, basically I don’t want to make a completely red painting and say it’s red because red makes me angry because I absolutely don’t believe in that. That being said, I do believe that color can be evocative through the relation of colors. So, I work backwards and get a feel for what I want the painting to be and then I make the palette from there. I’ve been getting more into earth pigments lately like here you can see, this is verona green earth from a store called Kremer Pigments in New York.

I’d say my approach to color usage is three-fold. The first being I use what I can get my hands on; second would be what I want the color relationships to be and what I want the sense of the painting to be; third would be me trying to add the body back into color. I want to try to add a lineage or a history back to my colors (even if its only my personal history) instead of using colors made by chemists in labs. There are restrictions to working this way of course because chemists can get way more varieties of colors. For example, purple used to be very rare because it was so hard to make synthetically. Working in the restrictions of what is naturally available there is a spectrum and there is a whole rainbow of every color naturally occurring in the world but they are much more muted. In other words, there isn’t infinite variability. I guess what I am trying to say is that I am working with the restrictions—author Maggie Nelson writes there is freedom to be found within constraints. I think restrictions can also be expansive too. People may think that working in restraints is limiting but I don’t think so.

AC: When the paintings are flush to the wall, they become part of the room, indeed, they’re adhered directly to the drywall. I want the paintings to recede into the room. I am not so into paintings that beat you over the head. I want my paintings to have a soft power and I feel that my role as the artist is to make that atmosphere in the painting. When the painting is finished it creates an atmosphere in the room. Painters often try to do this thing where the painting is the focal point of the room and I’m a bit skeptical of that. Like, what’s the point of that besides stroking your own ego? And, often the resulting work lacks subtlety. Like a painting can recede and be a part of the room. People have said that my paintings are a bit like wallpaper and I see no problem with that interpretation, even if I don’t necessarily agree. I want my viewers to feel like the work is a balm. I want my paintings to be a site for reunification. That is something I think painting can do is be a unifying force for parts of yourself, or with the world, or with relationships. Some artists want their paintings to induce fear and I just want my paintings to sing to me [laughs].

GT: There is such a tenderness that you seem to treat your materials with from your approach to brushstrokes and use of color that bear both levity and heavy undertones and they feel as though they are whispering in a sense. How do you go about choosing what colors or textures from piece to piece?

AC: Some of it is happenstance like we’ve talked about but the other aspect goes back to color relationships. It’s not that I believe that certain colors can elicit emotions, it's more that I think color relationships can elicit emotions. So, basically I don’t want to make a completely red painting and say it’s red because red makes me angry because I absolutely don’t believe in that. That being said, I do believe that color can be evocative through the relation of colors. So, I work backwards and get a feel for what I want the painting to be and then I make the palette from there. I’ve been getting more into earth pigments lately like here you can see, this is verona green earth from a store called Kremer Pigments in New York.

I’d say my approach to color usage is three-fold. The first being I use what I can get my hands on; second would be what I want the color relationships to be and what I want the sense of the painting to be; third would be me trying to add the body back into color. I want to try to add a lineage or a history back to my colors (even if its only my personal history) instead of using colors made by chemists in labs. There are restrictions to working this way of course because chemists can get way more varieties of colors. For example, purple used to be very rare because it was so hard to make synthetically. Working in the restrictions of what is naturally available there is a spectrum and there is a whole rainbow of every color naturally occurring in the world but they are much more muted. In other words, there isn’t infinite variability. I guess what I am trying to say is that I am working with the restrictions—author Maggie Nelson writes there is freedom to be found within constraints. I think restrictions can also be expansive too. People may think that working in restraints is limiting but I don’t think so.

GT: There are even distinct differences in texture and the way the paint lays on the canvas when using say acrylic paint in comparison to earth pigments. And it seems that when you compare the two, the synthetic paints lack that gentle and thoughtful touch and connection to earth that in turn makes it low-vibrational in comparison to earth derived pigments. And when using the natural pigments it probably makes the color relations so much more conversational because they are all from similar sources and on a level, they speak the same language or present themselves similarly because of their natural character.

AC: Yes, exactly! So low-vibrational and that will carry into the painting—you can feel that and sense it. The thing about acrylics is that plastics shed with time, so if you're painting with it or have it in your home, the plastic enters your home and body. There are literally plastic in our brains now! I believe that what you do to yourself, you do to others. If I am painting with acrylic paint and putting it into waterways, then necessarily, I am also putting paint into the waterways of my bloodstream.

AC: Yes, exactly! So low-vibrational and that will carry into the painting—you can feel that and sense it. The thing about acrylics is that plastics shed with time, so if you're painting with it or have it in your home, the plastic enters your home and body. There are literally plastic in our brains now! I believe that what you do to yourself, you do to others. If I am painting with acrylic paint and putting it into waterways, then necessarily, I am also putting paint into the waterways of my bloodstream.

GT: Yes, absolutley! Would you say that your practice is led more by proactive plans or by intuition?

AC: Intuition I do think is important when I am actually in front of the canvas and painting and being responsive to what is happening before my eyes and letting the painting unfold intuitively. Intuition is a kind of knowledge but it’s not something you can put your finger on. So, it’s hard to trust if it is truly logical because it can be influenced by anything you have experienced. My initial inspiration of why I want to make a painting comes from feeling maybe more than intuition. One of my favorite professors Lan Tuazon says, and I’m paraphrasing, “the aesthetic experience is when a known thought becomes a felt experience” which has really stuck with me. So, to have an aesthetic experience is when something you know becomes something that you feel. When you have goosebumps for example, that is when you have an aesthetic experience. Usually the starting point of a painting is based on an aesthetic experience. Basically, when I’m moved in the world, my brush moves on the canvas. So, I try to re-member through image-making [and by that I mean that I try to put back together] so that the painting retains a kind of power or force.

AC: Intuition I do think is important when I am actually in front of the canvas and painting and being responsive to what is happening before my eyes and letting the painting unfold intuitively. Intuition is a kind of knowledge but it’s not something you can put your finger on. So, it’s hard to trust if it is truly logical because it can be influenced by anything you have experienced. My initial inspiration of why I want to make a painting comes from feeling maybe more than intuition. One of my favorite professors Lan Tuazon says, and I’m paraphrasing, “the aesthetic experience is when a known thought becomes a felt experience” which has really stuck with me. So, to have an aesthetic experience is when something you know becomes something that you feel. When you have goosebumps for example, that is when you have an aesthetic experience. Usually the starting point of a painting is based on an aesthetic experience. Basically, when I’m moved in the world, my brush moves on the canvas. So, I try to re-member through image-making [and by that I mean that I try to put back together] so that the painting retains a kind of power or force.

GT: You seem to have had many great mentors and highly value mentorship. Is there a current piece of advice or moment with a mentor that has been on your mind a lot lately?

AC: Great question, and yes whenever I am in doubt I will hear them in my head. I don’t have any that I can think of right at this moment because they always come to me when I need it. My mom has this saying that has to do with memorizing scripture: the scripture comes to you when you need it. She means if you embody scripture then you become bound to it, and it becomes a part of you and will be there when you need it. I do feel that is true with what I hear; if I can commit something to heart it will come back when I need it. Sometimes it feels like you’re speaking in tongues but actually it’s just something you saw on TikTok [Laughs]. But, more seriously, it’s like a way of keeping those treasured people with you, to the point where it feels like those people speak through you almost.

GT: I can definitely say I've experienced those moments so many times throughout my life and it is such a comforting feeling when it does happen. So, shifting gears a little bit, I wanted to talk about what balance looks like for you in terms of juggling personal life, your practice and what advice you may have to others about what has worked for you?

AC: That is something that I am re-navigating a bit. It’s very easy for me to become consumed by my practice and let that be the only thing I care about. Sometimes it is at the detriment of other things that are important to me so I am restructuring now because I don’t want to lose what is important to me. It’s gotten to the point where I can’t let painting be to the deterioration of my own well-being and the people that I care about. Like with my partner who I live with now, I became a bit absent from the relationship because I am working full-time and was still trying to paint four days a week in the studio. I have these goals for myself and he wondered if I cared about him as much as my work and practice. I was in a pattern of working 9-5, and then going to the studio directly after until 10 or 11pm every other day. And then, when I would be physically present in the relationship, I would be exhausted.

Pacing has been a big consideration lately. If I was single I would be painting a lot more, but I don’t want to be single and I don’t want to live in isolation from my friends, family, and the people I care about. So, that means that the paintings change a bit. Now that I work full-time, I have to work much quicker so the work ends up being more gestural whereas before, I could be more manuscript-like. I used to spend 150 hours on one painting and I was fine with that. Now, I have to make paintings much quicker because of my relationships, wellbeing, and time constraints, which in turn all become incorporated into the form.

GT: I appreciate you being so open about that and it truly can be hard to manage time and feel that you are putting enough love and energy into each area of your life when you have a lot going on. Are there any new areas and goals you are reaching towards achieving at the moment in your practice?

AC: I want to make a painting that is circular and that envelops the viewer. I am interested in how painting produces space so I want the painting to become a space. The painting would be stretched across the walls and be all around you. In my residency with the Chicago Artist Coalition all the artists get a show, and I think what I want to do for my show is make a painting that you can step into.

GT: I am very excited to see where that takes you. I wanted to ask what is a challenge that you have had to overcome to bring you to where you are now?

AC: I think artistically, just taking the pressure off myself and knowing that everything happens in its own time. And that using brute force to make something happen is actually doing a disservice to yourself because if it is meant to happen, it will happen. Trying to force things doesn’t help anything or anyone. When I was in college in my junior and senior year I really wanted to be in a show. I look back on that time and I realize that my paintings weren’t ready to show at that time and I was still trying to find my voice in the work. Often when artists start showing too early, it’s bad for them because people then pigeonhole them or perceive them as making one kind of work. That happens naturally in the art world, you know, once you're on stage there is this pressure to make the same kinds of works that are expected of you. So, taking that pressure off and keeping my head down and focusing on the paintings has been something that I have had to learn.

AC: Great question, and yes whenever I am in doubt I will hear them in my head. I don’t have any that I can think of right at this moment because they always come to me when I need it. My mom has this saying that has to do with memorizing scripture: the scripture comes to you when you need it. She means if you embody scripture then you become bound to it, and it becomes a part of you and will be there when you need it. I do feel that is true with what I hear; if I can commit something to heart it will come back when I need it. Sometimes it feels like you’re speaking in tongues but actually it’s just something you saw on TikTok [Laughs]. But, more seriously, it’s like a way of keeping those treasured people with you, to the point where it feels like those people speak through you almost.

GT: I can definitely say I've experienced those moments so many times throughout my life and it is such a comforting feeling when it does happen. So, shifting gears a little bit, I wanted to talk about what balance looks like for you in terms of juggling personal life, your practice and what advice you may have to others about what has worked for you?

AC: That is something that I am re-navigating a bit. It’s very easy for me to become consumed by my practice and let that be the only thing I care about. Sometimes it is at the detriment of other things that are important to me so I am restructuring now because I don’t want to lose what is important to me. It’s gotten to the point where I can’t let painting be to the deterioration of my own well-being and the people that I care about. Like with my partner who I live with now, I became a bit absent from the relationship because I am working full-time and was still trying to paint four days a week in the studio. I have these goals for myself and he wondered if I cared about him as much as my work and practice. I was in a pattern of working 9-5, and then going to the studio directly after until 10 or 11pm every other day. And then, when I would be physically present in the relationship, I would be exhausted.

Pacing has been a big consideration lately. If I was single I would be painting a lot more, but I don’t want to be single and I don’t want to live in isolation from my friends, family, and the people I care about. So, that means that the paintings change a bit. Now that I work full-time, I have to work much quicker so the work ends up being more gestural whereas before, I could be more manuscript-like. I used to spend 150 hours on one painting and I was fine with that. Now, I have to make paintings much quicker because of my relationships, wellbeing, and time constraints, which in turn all become incorporated into the form.

GT: I appreciate you being so open about that and it truly can be hard to manage time and feel that you are putting enough love and energy into each area of your life when you have a lot going on. Are there any new areas and goals you are reaching towards achieving at the moment in your practice?

AC: I want to make a painting that is circular and that envelops the viewer. I am interested in how painting produces space so I want the painting to become a space. The painting would be stretched across the walls and be all around you. In my residency with the Chicago Artist Coalition all the artists get a show, and I think what I want to do for my show is make a painting that you can step into.

GT: I am very excited to see where that takes you. I wanted to ask what is a challenge that you have had to overcome to bring you to where you are now?

AC: I think artistically, just taking the pressure off myself and knowing that everything happens in its own time. And that using brute force to make something happen is actually doing a disservice to yourself because if it is meant to happen, it will happen. Trying to force things doesn’t help anything or anyone. When I was in college in my junior and senior year I really wanted to be in a show. I look back on that time and I realize that my paintings weren’t ready to show at that time and I was still trying to find my voice in the work. Often when artists start showing too early, it’s bad for them because people then pigeonhole them or perceive them as making one kind of work. That happens naturally in the art world, you know, once you're on stage there is this pressure to make the same kinds of works that are expected of you. So, taking that pressure off and keeping my head down and focusing on the paintings has been something that I have had to learn.

GT: Lastly, what’s next for you? You mentioned that you have a show coming up but is there anything else that you are looking forward to?

AC: I’m getting much more into printmaking which is a turn that I think will impact my paintings becoming more in conversation with print. At the moment I am working on etching with a studio called Pigeonhole Press, we’re preparing both an edition and a series of discrete monotypes. We etch together every Sunday so it is a weekly thing. I’ll have work in EXPO on Navy Pier this Spring for the first time, which has always been a goal for me. Also, I have a solo show coming up this summer at Povos Gallery. And I’m getting ready to make my first sculpture since college!

GT: This has been a delight, thank you so much for talking with me!

AC: Yes, thank you too!

AC: I’m getting much more into printmaking which is a turn that I think will impact my paintings becoming more in conversation with print. At the moment I am working on etching with a studio called Pigeonhole Press, we’re preparing both an edition and a series of discrete monotypes. We etch together every Sunday so it is a weekly thing. I’ll have work in EXPO on Navy Pier this Spring for the first time, which has always been a goal for me. Also, I have a solo show coming up this summer at Povos Gallery. And I’m getting ready to make my first sculpture since college!

GT: This has been a delight, thank you so much for talking with me!

AC: Yes, thank you too!

Abraham’s website: https://www.abrahamcone.com/.