INTERVIEW WITH CAROL BEDOY

by Rebecka Öhrström Kann 16/01/2024

Carol Bedoy is a curator and lens-based artist whose practice explores memory, care, and advocacy. By employing images from her vast family archive, Bedoy’s photographs investigate the sensory potency of images in relation to trauma and recollection. Attentive to the sinuous slips and flows of memory, Bedoy’s approach is one of tact as she navigates the intangible undercurrents beneath an image and the relationship between a photograph’s tactility and the haptic triggers of remembrance. We spoke about her work as a part of the Mexican-American artist collective Ni De Aquí, Ni De Allá, curating as a practice of care, and the influence of Peter Galassi’s 1991 show Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort at MoMA on her work.

Rebecka Öhrström Kann: To start, I was wondering if you could speak a little bit about your practice as an artist and a curator just for people who are not already familiar with your work.

Carol Bedoy: I'm Carol, and I'm a Mexican-American artist. Within my artistic and curatorial practice, I'm really interested in agency, advocacy, and just representing people who have most likely been portrayed in a negative light. Within my art practice, I like to experiment with photography, video, and printmaking. But that sort of made me spiral into curating during undergrad. Working with like a whole bunch of different artists of various backgrounds made me realize that my strong suit was mostly within curating and helping artists be shown in a light that they wish to be shown in.

RÖK: I feel like a lot of people I know who work with curating also have an art practice background within art. I think having that experience of making is really interesting as well. You grew up between Chicago and Aguascalientes, and I’m curious to hear how these two places have influenced your practice and interests as a curator and artist.

![Ni De Aquí, Ni De Allá, 'El Otro Lado,' at The Visual Arts Center, 2022. Image by Sandy Carlson.]()

![Ni De Aquí, Ni De Allá, 'El Otro Lado,' at The Visual Arts Center, 2022. Image by Sandy Carlson.]()

CB: I think they both have greatly impacted me and my practice. I think it's difficult to not have the space that you grew up in reflect who you are as a person. So, I'm definitely a big reflection of Chicago, Aguascalientes, and the road in between. Growing up, having done that road trip every single year, I feel like I've made home in all these little stops in between. I also think that growing up mostly in Chicago and having a very strong Mexican presence within that city definitely molded me. I first arrived at Logan Square, which at the time was a very different neighbourhood than it is today. It's been sort of interesting, now, too, living in London, a place that doesn't really have a Mexican community. But growing up seeing Mexican Americans and, like, fully native people from Mexico made me realize I was kind of neither. But I still found home in both of those places, and in terms of how they’ve impacted my practice today, I'm very certain that I want to spend the rest of my career in Aguascalientes. It’s a city with a really rich and extensive art history, and very classical artists are from there such as José Guadalupe Posada, who was a printmaker, and also Saturnino Herrán. They are both giant and influential Mexican artists who have impacted even larger artists like Diego Rivera and really shaped how Mexican art is viewed. Now I see that Aguascalientes doesn't have a contemporary art scene, and it makes me kind of sad that this place with such rich culture doesn't have much going on today. So, if curator is a stem of the word “to care,” I think Aguascalientes is the place I really want to invest my care into and bring a living and breathing art scene to that city.

RÖK: That’s so interesting, I didn't know that about connection between the word care and curation, but it fits so well into your practice. You talked about making that long road trip between Chicago and Aguascalientes, and the importance of borderlands or the space in between, which I know is also a central idea of Ni De Aquí, Ni De Allá, a collective of Mexican-American lens-based artists in Chicago of which you are also a part of. How did that come into being? How has the collective grown since its conception?

Carol Bedoy: I'm Carol, and I'm a Mexican-American artist. Within my artistic and curatorial practice, I'm really interested in agency, advocacy, and just representing people who have most likely been portrayed in a negative light. Within my art practice, I like to experiment with photography, video, and printmaking. But that sort of made me spiral into curating during undergrad. Working with like a whole bunch of different artists of various backgrounds made me realize that my strong suit was mostly within curating and helping artists be shown in a light that they wish to be shown in.

RÖK: I feel like a lot of people I know who work with curating also have an art practice background within art. I think having that experience of making is really interesting as well. You grew up between Chicago and Aguascalientes, and I’m curious to hear how these two places have influenced your practice and interests as a curator and artist.

CB: I think they both have greatly impacted me and my practice. I think it's difficult to not have the space that you grew up in reflect who you are as a person. So, I'm definitely a big reflection of Chicago, Aguascalientes, and the road in between. Growing up, having done that road trip every single year, I feel like I've made home in all these little stops in between. I also think that growing up mostly in Chicago and having a very strong Mexican presence within that city definitely molded me. I first arrived at Logan Square, which at the time was a very different neighbourhood than it is today. It's been sort of interesting, now, too, living in London, a place that doesn't really have a Mexican community. But growing up seeing Mexican Americans and, like, fully native people from Mexico made me realize I was kind of neither. But I still found home in both of those places, and in terms of how they’ve impacted my practice today, I'm very certain that I want to spend the rest of my career in Aguascalientes. It’s a city with a really rich and extensive art history, and very classical artists are from there such as José Guadalupe Posada, who was a printmaker, and also Saturnino Herrán. They are both giant and influential Mexican artists who have impacted even larger artists like Diego Rivera and really shaped how Mexican art is viewed. Now I see that Aguascalientes doesn't have a contemporary art scene, and it makes me kind of sad that this place with such rich culture doesn't have much going on today. So, if curator is a stem of the word “to care,” I think Aguascalientes is the place I really want to invest my care into and bring a living and breathing art scene to that city.

RÖK: That’s so interesting, I didn't know that about connection between the word care and curation, but it fits so well into your practice. You talked about making that long road trip between Chicago and Aguascalientes, and the importance of borderlands or the space in between, which I know is also a central idea of Ni De Aquí, Ni De Allá, a collective of Mexican-American lens-based artists in Chicago of which you are also a part of. How did that come into being? How has the collective grown since its conception?

CB: Max and Jennifer met during Latoya Ruby Frazier's class, in SAIC and they just kind of realized how many overlapping themes they had within their work. None of us were really friends before so it was kind of funny how we all came together. Like, I think me and Jennifer had similar friends, and Max and Sophie had classes together. So it was just sort of like, reaching out, like, “Hey, I like your work, would you like to FaceTime and just talk?” [laughs]. I think we definitely took advantage of all the free time we had during COVID, and when the four of us started talking, we started to see all these connections and, just like how well-rounded Mexican American experience we give to each other in our conversations. We're from different parts of Mexico, and all our parents have very different migration histories coming into the US and have had to deal with very different things growing up. But we still felt super connected with racist policies that affected all of us, and the labour with our parents in how their bodies have been, like worn to the bone. And, just like the constant theme of generational trauma and inheriting all of these horrible things that our parents have had to experience just to give us the privilege to, like, pursue conceptual art. I think we started talking and seeing all the constant themes playing around with each other's images, and it was a super collaborative process. When we saw open calls, we were like, “We should apply for an exhibition: we have all this writing, we have all of these like stories we want to tell, Let's just go for it.”

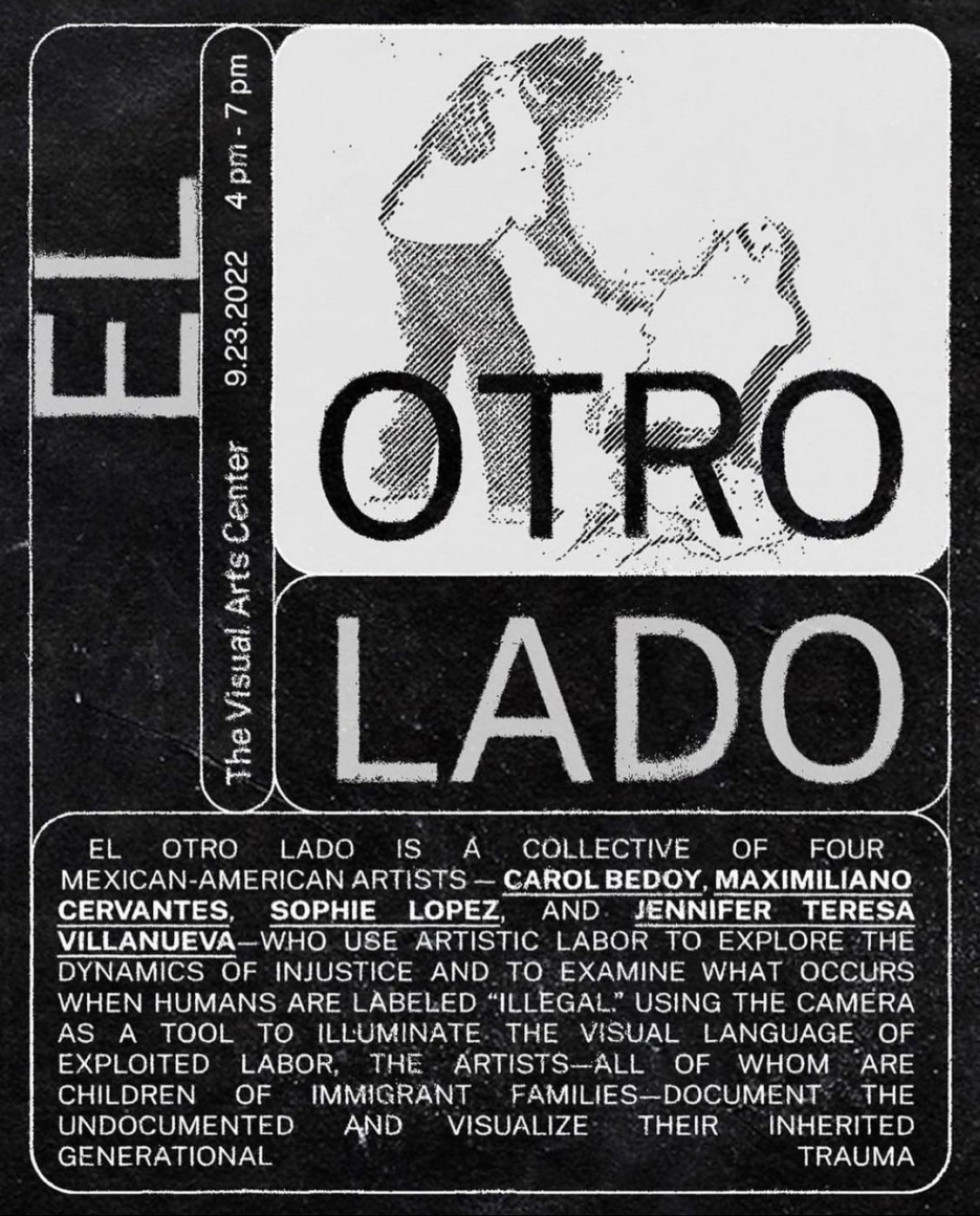

CB: The first exhibition happened at Heaven Gallery. It was a really interesting experience having that being our first time showing outside of SAIC. But I think we all felt unsatisfied after that exhibition. So we decided to apply to Filter Photo’s exhibition call, having updated all our texts, our ideas and the whole conversation. We applied at the same time for the Visual Arts Centre in Austin, TX, and we were also interested in how that audience would receive it, being closer to the border. Even though it was the same ideas and the same show, basically, between our El Otro Lado exhibition at Filter and in Austin, I feel like it fed us very different things. And just seeing ourselves develop and pushing each other creatively to pursue things that maybe we hadn't thought of has been great and it’s been like a very lovely experience just to collaborate with Jennifer, Max, and Sophie. We’ve all sort of dispersed into different areas, like Jennifer is at the Whitney right now, during the ISP program, Max is finishing up his masters, and Sophie has pursued welding, which is amazing. And I'm over here in London doing this program [New Curators], under someone I’ve looked up to for so long, Mark Godfrey. So I don't know if an exhibition will be the next step for us. But we're all definitely still in touch and telling each other about what we're up to. I think our next step is probably going to be digitally based, but hopefully, we can do another exhibition again in the future.

RÖK: I'd love to see that translated digitally as well. I was curious, also, if you could talk a little bit about your curatorial approach, just sort of your interests as a curator, or things you think about when you're curating.

CB: Like I mentioned earlier, I'm big on advocacy. I think having an artistic practice myself has taught me a lot about what it’s like coming into a space as an artist, how you're treated, and the experience of being vulnerable in a space, especially with the work I make. And I find that a lot of spaces haven't really shown me respect, and I just want to be a kinder face within these institutions. I just really appreciate confessional work, honest work, and raw work. Things that sort of made me feel comfortable with what I've experienced, and I can relate to, but also work that gives me a view into a world that I would have never known about if I hadn't spoken to this artist or experienced their work. So, I think my approach is definitely more on the emotional side. I definitely take a mama bear approach [laughs], especially whenever I'm working with a group curating. Another huge part of my curatorial practice is also within social programming. I hadn't seen the importance of social programming until I started working at SITE galleries at SAIC during my undergrad. Just seeing how food, dancing, or simply a specific type of music can make space for a person in a space where they didn't feel welcome before. And I'm probably bringing up this example just because it's the most recent one, but we had like a carne asada at our last exhibition at Filter[Filter Photo]. And my parents had never been to one of my exhibitions because they felt like it was too stuffy, not for them, people are gonna look at them weirdly. And just kind of naming our opening reception, like a cookout, I think, made them feel a little bit more comfortable to, like, step into the space. It was really comforting seeing my family interact with the other artists’ families, and seeing themselves literally on the walls and really finding their space within an art space that they hadn't seen before. And it's really important to me, because I didn't step into an art museum or gallery until I was like 17. And that's mostly because my parents didn't think that it was, like, the spot for us. They were like, “We're labour workers, you're probably going to go into a labour-intensive job, what are we going to go and look at pretty paintings for?” And I’m just like, now being on the other side, kind of having an in on the world. That feeling makes me really sad because I just want people within a community to be able to go and experience art and open up their minds to experience different things, and I think social programming is a wonderful opportunity to sort of activate the walls beyond the walls.

CB: Like I mentioned earlier, I'm big on advocacy. I think having an artistic practice myself has taught me a lot about what it’s like coming into a space as an artist, how you're treated, and the experience of being vulnerable in a space, especially with the work I make. And I find that a lot of spaces haven't really shown me respect, and I just want to be a kinder face within these institutions. I just really appreciate confessional work, honest work, and raw work. Things that sort of made me feel comfortable with what I've experienced, and I can relate to, but also work that gives me a view into a world that I would have never known about if I hadn't spoken to this artist or experienced their work. So, I think my approach is definitely more on the emotional side. I definitely take a mama bear approach [laughs], especially whenever I'm working with a group curating. Another huge part of my curatorial practice is also within social programming. I hadn't seen the importance of social programming until I started working at SITE galleries at SAIC during my undergrad. Just seeing how food, dancing, or simply a specific type of music can make space for a person in a space where they didn't feel welcome before. And I'm probably bringing up this example just because it's the most recent one, but we had like a carne asada at our last exhibition at Filter[Filter Photo]. And my parents had never been to one of my exhibitions because they felt like it was too stuffy, not for them, people are gonna look at them weirdly. And just kind of naming our opening reception, like a cookout, I think, made them feel a little bit more comfortable to, like, step into the space. It was really comforting seeing my family interact with the other artists’ families, and seeing themselves literally on the walls and really finding their space within an art space that they hadn't seen before. And it's really important to me, because I didn't step into an art museum or gallery until I was like 17. And that's mostly because my parents didn't think that it was, like, the spot for us. They were like, “We're labour workers, you're probably going to go into a labour-intensive job, what are we going to go and look at pretty paintings for?” And I’m just like, now being on the other side, kind of having an in on the world. That feeling makes me really sad because I just want people within a community to be able to go and experience art and open up their minds to experience different things, and I think social programming is a wonderful opportunity to sort of activate the walls beyond the walls.

RÖK: An exhibition is so much more than just like, you know, the wall.

CB: Yeah! It’s the community you’re in, and like the context of what that place has shown before. The gallery is people-activated so bringing people into the space and making them feel comfortable is really important.

CB: Yeah! It’s the community you’re in, and like the context of what that place has shown before. The gallery is people-activated so bringing people into the space and making them feel comfortable is really important.

RÖK: I’m interested in how your curatorial work relates to your artistic creative practice or how they might feed into one another?

CB: I definitely feel like neither would exist without the other. I always knew that I had an interest towards the arts, an interest towards object making. But I didn't really have access to any sort of, like, art background, prior to art school. So I think figuring out my footing as a visual artist first, was really crucial to being able to develop into a curator. I just think having a developed artistic practice, where I talk about really sad things that have happened to me and kind of just go through that whole process to be able to produce work, makes me really appreciate the vulnerability and the honesty that artists have towards their work, and just how special it is to them. And not to sound shady, but I feel like a lot of, like, only art historian-background curators kind of lack that. They don't have that personal touch of, honestly, the experience of feeling naked within your work, and being able to, like, approach it like in a very careful way. I think particularly now I feel like I’m sort of in a difficult spot because starting this program with the New Curators, we're sort of seeing a clear separation between being an artist/being a curator and learning about artists who started curating and artists who curate and include their work in their own shows. I’m sort of scared of the implications of curating and also including your own work, and what it means in the long run for an artist/curator. So I'm sort of blue of how that happened. Like I helped curate, and then I included my work. So that makes me feel a little funny. I'm just trying to learn and develop my relationship towards the two different roles, but it's really hard to do that because I honestly think I couldn’t be a curator if I wasn't an artist, and I couldn't be an artist if I wasn't a curator.

RÖK: No, that makes a lot of sense. I feel like especially thinking about your use of the archive, for example, and like to what extent that is a form of curating of your family's albums and blurring those lines between artist and curator. But I’m curious to hear, which curators, artists, writers, and other creative thinkers have influenced your curatorial and creative practice?

CB: I'm actually a huge fan of Nan Goldin. And she's an artist who has curated shows where she's been deeply applauded for, like, not including her work in the shows. And I find that really interesting because, especially in her show, Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing at Artists Space in 1989, her work could definitely have been in that show. Living in New York in the midst of the AIDS pandemic, she had friends and close loved ones who were dying. And I'm sure that was reflected in her work, especially because she made work about the people and the world around her so much. Just like that exclusive denial of her own voice within the show, but I guess it’s because she chose to navigate the gaze instead. So, I love Nan Goldin, and I love learning from her. But some other people are Peter Galassi, who burst my love of curating with his show Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort at MoMA in 1991 was actually a huge influence for Ni De Aquí, Ni De Allá in thinking about how the domestic space reflects so much of a person and how many parallels there are regardless of like race, gender, and other factors that might separate us, we'll have this common experience. I found it really beautiful, and it made me see how the association between images could really make magic and tell you a story. So he's another big love of mine. And I think, finally, in terms of my curatorial practice, I really love Maureen Paley. I got to meet her this year, which was, like, insane. And it's just been really interesting learning about her being an American who moved to London and established an art scene in London's East when there weren’t any galleries in the area. I also love how proud she is of all the artists she represents. Like, she really represents people like Wolfgang Tillmans, and gave him his first show when he was so young. It just brings me a lot of comfort because I had such a distaste for commercial galleries. But hearing how intentional and how much she cares about every single artist kind of gave me hope within the field because, unfortunately, money does have to flow to make this happen. And I was becoming so disheartened of galleries just thinking about things like, “What's gonna sell, what's trending, what's popular?” And then seeing, more importantly, “Who do I believe in? What do I want to give the space to?” So it was a huge moment meeting her.

RÖK: I feel like that aspect of care seems to be a red thread in your practice, and the importance of not only caring for the work presented in the gallery but also the artist’s being vulnerable in that space and making sure people feel comfortable and represented.

CB: I think it's a really vital connection, and you can really feel it in that space.

CB: I definitely feel like neither would exist without the other. I always knew that I had an interest towards the arts, an interest towards object making. But I didn't really have access to any sort of, like, art background, prior to art school. So I think figuring out my footing as a visual artist first, was really crucial to being able to develop into a curator. I just think having a developed artistic practice, where I talk about really sad things that have happened to me and kind of just go through that whole process to be able to produce work, makes me really appreciate the vulnerability and the honesty that artists have towards their work, and just how special it is to them. And not to sound shady, but I feel like a lot of, like, only art historian-background curators kind of lack that. They don't have that personal touch of, honestly, the experience of feeling naked within your work, and being able to, like, approach it like in a very careful way. I think particularly now I feel like I’m sort of in a difficult spot because starting this program with the New Curators, we're sort of seeing a clear separation between being an artist/being a curator and learning about artists who started curating and artists who curate and include their work in their own shows. I’m sort of scared of the implications of curating and also including your own work, and what it means in the long run for an artist/curator. So I'm sort of blue of how that happened. Like I helped curate, and then I included my work. So that makes me feel a little funny. I'm just trying to learn and develop my relationship towards the two different roles, but it's really hard to do that because I honestly think I couldn’t be a curator if I wasn't an artist, and I couldn't be an artist if I wasn't a curator.

RÖK: No, that makes a lot of sense. I feel like especially thinking about your use of the archive, for example, and like to what extent that is a form of curating of your family's albums and blurring those lines between artist and curator. But I’m curious to hear, which curators, artists, writers, and other creative thinkers have influenced your curatorial and creative practice?

CB: I'm actually a huge fan of Nan Goldin. And she's an artist who has curated shows where she's been deeply applauded for, like, not including her work in the shows. And I find that really interesting because, especially in her show, Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing at Artists Space in 1989, her work could definitely have been in that show. Living in New York in the midst of the AIDS pandemic, she had friends and close loved ones who were dying. And I'm sure that was reflected in her work, especially because she made work about the people and the world around her so much. Just like that exclusive denial of her own voice within the show, but I guess it’s because she chose to navigate the gaze instead. So, I love Nan Goldin, and I love learning from her. But some other people are Peter Galassi, who burst my love of curating with his show Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort at MoMA in 1991 was actually a huge influence for Ni De Aquí, Ni De Allá in thinking about how the domestic space reflects so much of a person and how many parallels there are regardless of like race, gender, and other factors that might separate us, we'll have this common experience. I found it really beautiful, and it made me see how the association between images could really make magic and tell you a story. So he's another big love of mine. And I think, finally, in terms of my curatorial practice, I really love Maureen Paley. I got to meet her this year, which was, like, insane. And it's just been really interesting learning about her being an American who moved to London and established an art scene in London's East when there weren’t any galleries in the area. I also love how proud she is of all the artists she represents. Like, she really represents people like Wolfgang Tillmans, and gave him his first show when he was so young. It just brings me a lot of comfort because I had such a distaste for commercial galleries. But hearing how intentional and how much she cares about every single artist kind of gave me hope within the field because, unfortunately, money does have to flow to make this happen. And I was becoming so disheartened of galleries just thinking about things like, “What's gonna sell, what's trending, what's popular?” And then seeing, more importantly, “Who do I believe in? What do I want to give the space to?” So it was a huge moment meeting her.

RÖK: I feel like that aspect of care seems to be a red thread in your practice, and the importance of not only caring for the work presented in the gallery but also the artist’s being vulnerable in that space and making sure people feel comfortable and represented.

CB: I think it's a really vital connection, and you can really feel it in that space.

RÖK: I’m interested in your activation of the archive, particularly working with your own family archive. How did it enter your practice(or has it always been there)? Do you feel like your relationship with the archive has changed after using it in your work?

CB: I think the archive has always been there ever since I was a little kid and I think it’s one of the things that activated my interest in visuals. And it was mostly seeking stories that I didn't have. I found that these people kind of built up to me, led to me, and I couldn't stand that I would flip through an album, see a person and not know who they were. So it definitely started from a very early age, just like flipping through my archive, rearranging how my mom organised it.

RÖK: A young curator!

CB: Yes! [laughs].

CB: I think the archive has always been there ever since I was a little kid and I think it’s one of the things that activated my interest in visuals. And it was mostly seeking stories that I didn't have. I found that these people kind of built up to me, led to me, and I couldn't stand that I would flip through an album, see a person and not know who they were. So it definitely started from a very early age, just like flipping through my archive, rearranging how my mom organised it.

RÖK: A young curator!

CB: Yes! [laughs].

CB: My mom would get mad about it like, “these are from completely different pages” when I’d move them around [laughs]. But it's interesting because I originally started at SAIC in painting and drawing, specifically in the art therapy department. But I took a large format class and accidentally became a photographer. And it was mostly because I liked old photos. I liked the feel of them. So I was like, let's learn the most ancient camera that's literally just a lightbox [laughs]. However I found myself gravitating towards imagery that I saw within the archive. Hanging sheets, patios, vegetation, and all these family parties. I was just so stuck within that image swirling in my head and knowing the implications of trauma that happened at those parties and different sensory activators that are hidden within the image. So that definitely led into my image-making, but then that kind of spiraled into, like, what if I use the actual photos because there's no way I can recreate them. I think one that I'm particularly thinking about is, this photograph of my grandpa on his patio at his mom's house. And I'm physically not allowed in that house. Like I've tried multiple times to like step in and take photos. The only times I've experienced this are through photographs. Just because like my great-grandmother died when she was 100 years old, but I was three. So, I don't have a clear image in my head, I'm mostly learning through the archive what that place was like. So I was like, “Okay, fine, let's just use the actual photo. I can't retake it. Let's just use the physical photos.” And also, I'm kind of starting to develop an idea of what if these photos are like actual objects? Like for one of my most recent works, called La Vieja de Jose Reyes Martinez (2023), which translates to that lady from the street, which is where my grandmother's house is. So my grandparents experienced a divorce, and as the archivist of the family, whenever I go into anyone's house, I'm like, “Okay, pull it out,” Like, I'm gonna scan every single photo you have [laughs]. But I was flipping through my uncle's pictures, and I found one half of him, my mom and my aunt, and their house. And then, flipping through my grandma's archive there was a picture of her in front of the house. And I'm like, “Oh, my god, they’re the same thing.” So I think I just started, registering these little secrets within these images, and being able to draw them back together made me realize that these are like family artifacts, an actual object, and a manifestation of my grandparents' divorce. So, I think that's definitely taking me in a new direction. And how my relationship with the archive stands right now. I've definitely been granted a grand archivist position within my family. So that's been interesting to navigate, like, every birthday, every special occasion, or when someone passes away, they're like, “Hey, do you have pictures of this person?” But I also think it makes me really curious about other people's archives and wanting to see them and see if I find any similarities.

RÖK: I love that instead of the family photographer you have become the family archivist. But I think what you were saying about the physicality of images here is so important. I find photography such an interesting medium, because we touch photographs and have that very tactile relationship with them that we don’t have with other forms. They acquire a very intimate material memory of their owners and encounters. Your practice as a curator and artist explores memory as in transition, molding to new social and physical environments of communities and individual narratives. Could you talk a little bit about the importance of memory and memory-making in your work?

CB: I guess memory is a primary focus within my work just because of my personal views of how these experiences, traumas, and things that just happened to you kind of amount to who you are right now. I think a lot of people don't have that approach and see each day with a fresh set of eyes, like, “sure, this has happened, I'm gonna have a disconnect from it.” But then keep finding themselves in those situations again, and it's because you're not referencing back to the root causes that you have to address in order to heal and start treading a different path. I definitely find that vital, just to process mental health. Like I said I have an art therapy background and interest so I find visual art making such an important tool to be able to, like, get past very unfortunate things that happen and are just part of the human experience. It just really helps you to make peace with it, to be able to move on. The other aspect of memory within my work is that there's a certain access even to your own story that you don't have without the archive. Like I can tell you, I had a Pokemon cake when I was three years old, but I don't remember it. I only know because I have a family video of it and some pictures. But I find it really important to just be able to digest the past to set yourself up for success in the future and I guess that's sort of what I try to do for myself through my work.

![Thinning, Carol Bedoy, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.]()

RÖK: I’m curious if you could talk a little about your interest in exploring tensions between the visible and the invisible. I’m thinking particularly about your use of soft, dream-like imagery and focus on details as a means to examine topics that are often very difficult and painful, such as intergenerational trauma or experiences of migration.

CB: My use of dreamlike and overall beautiful imagery is to make it easier to talk about, just for myself. I tried exploring more graphic imagery and visual simulations that relate more closely to the subject matter, but I found myself sort of retraumatizing myself. So I was like, “I enjoy pretty things, I’m going to take that route,” and just grounding these things that have such negative stimulation in my head and being able to regear them. One specific work that I have in mind is my piece Thinning (2019), which is a large-format photograph of grapefruit. It looks like a very standard still life, but the story behind the image was that I was actually addressing my eating disorder that I struggled with all throughout my adolescence, and for two years, all I would eat was like citrus. And for the longest time, the smell of citrus would trigger me. But after making that photograph and going through the whole sensory experience during its production I now have a way more positive relationship with citrus. Like I remember smelling it and the juice dripping down my hands while I was working on it and being like I guess I have to lick it. So that’s one particular example of how I use beautiful imagery to reassociate negative things from my memory.

RÖK: I love that instead of the family photographer you have become the family archivist. But I think what you were saying about the physicality of images here is so important. I find photography such an interesting medium, because we touch photographs and have that very tactile relationship with them that we don’t have with other forms. They acquire a very intimate material memory of their owners and encounters. Your practice as a curator and artist explores memory as in transition, molding to new social and physical environments of communities and individual narratives. Could you talk a little bit about the importance of memory and memory-making in your work?

CB: I guess memory is a primary focus within my work just because of my personal views of how these experiences, traumas, and things that just happened to you kind of amount to who you are right now. I think a lot of people don't have that approach and see each day with a fresh set of eyes, like, “sure, this has happened, I'm gonna have a disconnect from it.” But then keep finding themselves in those situations again, and it's because you're not referencing back to the root causes that you have to address in order to heal and start treading a different path. I definitely find that vital, just to process mental health. Like I said I have an art therapy background and interest so I find visual art making such an important tool to be able to, like, get past very unfortunate things that happen and are just part of the human experience. It just really helps you to make peace with it, to be able to move on. The other aspect of memory within my work is that there's a certain access even to your own story that you don't have without the archive. Like I can tell you, I had a Pokemon cake when I was three years old, but I don't remember it. I only know because I have a family video of it and some pictures. But I find it really important to just be able to digest the past to set yourself up for success in the future and I guess that's sort of what I try to do for myself through my work.

RÖK: I’m curious if you could talk a little about your interest in exploring tensions between the visible and the invisible. I’m thinking particularly about your use of soft, dream-like imagery and focus on details as a means to examine topics that are often very difficult and painful, such as intergenerational trauma or experiences of migration.

CB: My use of dreamlike and overall beautiful imagery is to make it easier to talk about, just for myself. I tried exploring more graphic imagery and visual simulations that relate more closely to the subject matter, but I found myself sort of retraumatizing myself. So I was like, “I enjoy pretty things, I’m going to take that route,” and just grounding these things that have such negative stimulation in my head and being able to regear them. One specific work that I have in mind is my piece Thinning (2019), which is a large-format photograph of grapefruit. It looks like a very standard still life, but the story behind the image was that I was actually addressing my eating disorder that I struggled with all throughout my adolescence, and for two years, all I would eat was like citrus. And for the longest time, the smell of citrus would trigger me. But after making that photograph and going through the whole sensory experience during its production I now have a way more positive relationship with citrus. Like I remember smelling it and the juice dripping down my hands while I was working on it and being like I guess I have to lick it. So that’s one particular example of how I use beautiful imagery to reassociate negative things from my memory.