INTERVIEW WITH ERICA MCKEEHEN

By Giselle Torres 11/10/2023

By Giselle Torres 11/10/2023

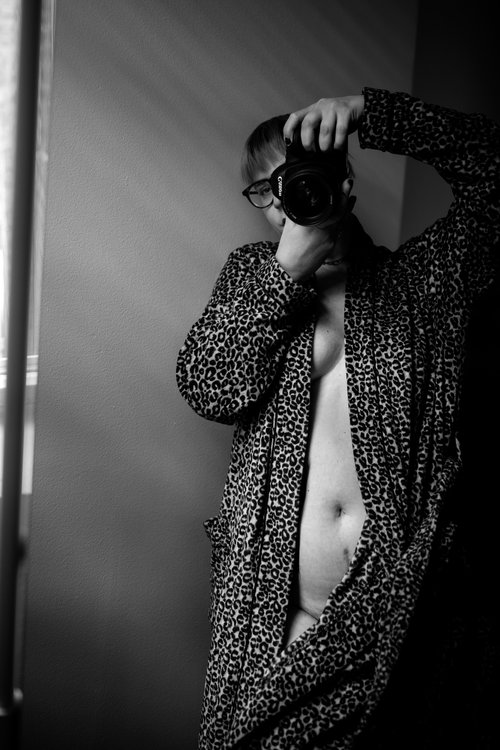

Erica McKeehen: I’ve been making images, I guess more “officially,” since I saved up and bought my first digital point-and-shoot camera in 2003 (I was 16). At first, I was only making self-portraits for my blog. Blogs were big back then, and I wanted people to know what I looked like. By the time I was interested in pursuing photography more seriously, I took my high school teacher’s advice and bought a 35mm film camera. It had manual controls, but I didn’t know how to use them. I still loved the experience of getting the film developed at CVS and discovering surprises and successes in my images. I used this camera to make a “portfolio” (I feel so embarrassed even calling it that) to get into the undergraduate Visual Communication program at Ohio University — where, I was told upon interviewing, that I would be a better fit (based on the constructed/posed nature of my images) for the Commercial track rather than my original interest, Photojournalism.

At the time, Katina was a budding local burlesque performer. David and Katina were also Midwest transplants, having just moved from Michigan. After attending one of her earlier burlesque performances, my first-ever experiece witnessing striptease, I convinced myself that I too needed burlesque.

I did not have theater, performance, or dance experience prior to burlesque, but the desire to excel so that I could take the stage one day drove me to take at least a dozen burlesque classes in the span of a year, signing up for my first class as a 30th birthday present. Like Katina, I quickly aligned with burlesque’s ability to disrupt the status quo. Through reveals, and through bodies unafraid of taking up space for their own sake, we explore masquerade and sexual freedom.

I didn’t consider “fine art photography” a serious pursuit. Fine art seemed way too abstract in terms of a career path. (I know now it’s only because no one ever demonstrated to me that that COULD be a path for me early on as a creative person.) So, though my style of image-making and my thoughts about it have greatly shifted throughout the years, my core interests in constructing portraits, as well as using myself as a subject of the work, have remained the same for 20 years — over half my life.

My experience as a performer has less of a lifespan. In another life, during my five-year-stint managing a Starbucks café, I hired and subsequently befriended a barista named David Alejandro. In time, after figuring out we both shared an enthusiasm for rock music and sneaking into live shows at venues near our store, he introduced me to

his then-girlfriend-now-wife, my absolute best friend, Kitty Tornado (Katina).

Katina and David moved away from Chicago in 2019. I thought they were gone for good, especially when they told me that they planned to move to Spain to live after they got married in the summer of 2021. In the summer of 2022, thanks to being awarded the Stuart Abelson Graduate Research Fellowship through the Photography department at Columbia College Chicago, I was able to visit my best friends in Spain and travel the country with them. During our Spain reunion, Katina and David announced their plans to move back to Chicago at the end of the summer. Katina and I immediately agreed that we needed to fulfill a dream we’ve talked about since meeting – and produce our own rock n’ roll-themed burlesque show.

So, really, I have Katina to thank for a lot. For bringing photography and collaborative artmaking back into my life full force, for helping me to strengthen and bring meaning to my visual work in the final year of my MFA, and for introducing me to burlesque which has forever changed my life and my own set of concerns as a maker, educator, and activist.

![Vivi Means "Lively" (Obscura at Simone's) Erica McKeehen, 2022]()

So, really, I have Katina to thank for a lot. For bringing photography and collaborative artmaking back into my life full force, for helping me to strengthen and bring meaning to my visual work in the final year of my MFA, and for introducing me to burlesque which has forever changed my life and my own set of concerns as a maker, educator, and activist.

GT: As you just mentioned, you are a co-founder of the burlesque production/show, “Lust for Life,” with your best frind, Katina upon ample other creative endeavors you pursue. With this in mind, what advice would you be able to give to other ambitious individuals?

EM: Motivating myself is difficult with the stress of job-hunting post-graduate school. Last year was a whirlwind. I am not the best at giving all areas of my life the attention they deserve! My advice to anyone trying to fight the good fight in this increasingly complex world (with limited resources, especially): You must find your people.

Find people you can celebrate success with but also fall apart in front of. Try to make those people integral to what you do, like I have with my friends, and they will carry you along in many areas of your life. Be open to what those people must share with you. Be open to change. Be open to difficult realizations. Be open to periods of inactivity and do not punish yourself for slow times.

I make a lot of to-do lists and notes. I have over 150 notes on the Notes app between my phone and computer and find that organizing my day digitally creates the most flexibility. I love the look and feel of a paper planner, but my life has become so chaotic that the constant erasing and crossing out would drive me nuts. (I should clarify that I live with OCD.) You must create systems of accountability for yourself, especially out of school. Make your work COLLABORATIVE in some way so that you always have more than one perspective in what you put out in the world. No good work exists in a vacuum.

EM: Motivating myself is difficult with the stress of job-hunting post-graduate school. Last year was a whirlwind. I am not the best at giving all areas of my life the attention they deserve! My advice to anyone trying to fight the good fight in this increasingly complex world (with limited resources, especially): You must find your people.

Find people you can celebrate success with but also fall apart in front of. Try to make those people integral to what you do, like I have with my friends, and they will carry you along in many areas of your life. Be open to what those people must share with you. Be open to change. Be open to difficult realizations. Be open to periods of inactivity and do not punish yourself for slow times.

I make a lot of to-do lists and notes. I have over 150 notes on the Notes app between my phone and computer and find that organizing my day digitally creates the most flexibility. I love the look and feel of a paper planner, but my life has become so chaotic that the constant erasing and crossing out would drive me nuts. (I should clarify that I live with OCD.) You must create systems of accountability for yourself, especially out of school. Make your work COLLABORATIVE in some way so that you always have more than one perspective in what you put out in the world. No good work exists in a vacuum.

G: Throughout your body of photographic work, many people peer straight into your lens while others are caught in an ephemeral warmth while performing or even brushing their hair such as in the stunning image, Brushing (2022). None of the individuals feel posed and if they are, they appear confident, comfortable, and at ease. It seems like you provide them with agency over how they are seen. Would you say that this is an intention of yours?

EM: I think to dedicate oneself to portraiture as much as I do, one must be perpetually and endlessly curious about others. Attentive to their personas and presentations. Curiosity always drives me to return to photographing people because, as it’s been said, every person’s life is endlessly complex and fascinating — especially under the kind of scrutiny that building long-term portrayals requires. Close looking at portraits brings us closer to examining, challenging, and ultimately understanding ourselves.

Portraits of rock stars made a huge impact on me in my youth, probably because these larger-than-life icons seemed more accessible as people through photographic depictions. I make portraits currently of myself and of communities involved in burlesque performance and other adjacent forms of sex work because, through portraiture, I can help shape an alternative narrative that honors, rather than minimizes, the people that I know. Nothing compares to the specific and intense exchange of staring into a subject’s eyes, especially if you never get to know them beyond that.

EM: I think to dedicate oneself to portraiture as much as I do, one must be perpetually and endlessly curious about others. Attentive to their personas and presentations. Curiosity always drives me to return to photographing people because, as it’s been said, every person’s life is endlessly complex and fascinating — especially under the kind of scrutiny that building long-term portrayals requires. Close looking at portraits brings us closer to examining, challenging, and ultimately understanding ourselves.

Portraits of rock stars made a huge impact on me in my youth, probably because these larger-than-life icons seemed more accessible as people through photographic depictions. I make portraits currently of myself and of communities involved in burlesque performance and other adjacent forms of sex work because, through portraiture, I can help shape an alternative narrative that honors, rather than minimizes, the people that I know. Nothing compares to the specific and intense exchange of staring into a subject’s eyes, especially if you never get to know them beyond that.

My research has shown me that although photography’s descriptive nature can foster understanding and compassion for others, it can also perpetuate reductive portrayals that further harm, rather than help, entire communities. In general, the history of the photographic medium demonstrates how image-makers have leveraged their artistic opportunity and positionality to depict the other. Unlike so many, I resist spectacle and instead root my photographic work in creative community and comradery to present nuanced and caring views.

![Highness Noire Watching Shimmy LaRoux and Switch the Boi Wonder (Embodiment at The Newport Theater), Erica Mckeehen, 2022]()

G: When discussing this interview beforehand, you mentioned to me how important it would be for you to shine light upon common misconceptions about sex work and burlesque and the relationship between the two. Both are practices that are viewed as taboo or to be discussed in hushed tones in our culture. What are the misunderstandings about the two that you are aware of and would like to address?

EM: Prior to taking on sex work more generally, I performed regularly as part of a showgirl ensemble (burlesque) with Katina and others until COVID forced venues to close for over a year. To make up for the money lost from canceled gigs, I started selling sexual content online at the advice and mentorship of my friend, fellow burlesque performer and sex worker, Secret Mermaid. Once I established my OnlyFans, I aligned myself with other sex workers (although sex work takes on many different forms).

While some people don’t consider burlesque a form of “real” sex work (sex work being the exchange of sexual goods or services for compensation), my research and visual practice insist otherwise – and, the fact is, most performers have trades in the broader sex industry. Skills cultivated in burlesque are transferrable to other trades, thus my work deals broadly with sex work, and I consider burlesque a branch of that tree (especially as burlesque shows were the original strip clubs and sought-out sources of adult entertainment, before sex could be consumed via magazines, film, and the Internet).

So, one misconception that is glaring whenever I talk about my work is that burlesque must be defined as either totally or totally not sex work. I leave it up to the subjects I work with to identify themselves how they wish – and to view their art and participation in the burlesque community in whatever way suits them.

EM: Prior to taking on sex work more generally, I performed regularly as part of a showgirl ensemble (burlesque) with Katina and others until COVID forced venues to close for over a year. To make up for the money lost from canceled gigs, I started selling sexual content online at the advice and mentorship of my friend, fellow burlesque performer and sex worker, Secret Mermaid. Once I established my OnlyFans, I aligned myself with other sex workers (although sex work takes on many different forms).

While some people don’t consider burlesque a form of “real” sex work (sex work being the exchange of sexual goods or services for compensation), my research and visual practice insist otherwise – and, the fact is, most performers have trades in the broader sex industry. Skills cultivated in burlesque are transferrable to other trades, thus my work deals broadly with sex work, and I consider burlesque a branch of that tree (especially as burlesque shows were the original strip clubs and sought-out sources of adult entertainment, before sex could be consumed via magazines, film, and the Internet).

So, one misconception that is glaring whenever I talk about my work is that burlesque must be defined as either totally or totally not sex work. I leave it up to the subjects I work with to identify themselves how they wish – and to view their art and participation in the burlesque community in whatever way suits them.

However, despite how I “set up” my work verbally / in writing for viewership / discussion / interpretation, I think people feel “safe” and more comfortable engaging in burlesque as a topic – about ME as a burlesquer, and about my subjects (in my work) as burlesquers (rather than as SWers ALSO, even though subjects in my work are also strippers and full-service workers or “escorts” in addition to burlesque entertainers). And even though I have said that I am a sex worker time and time again – and that I sell adult content online – many of my peers at CCC did not want to touch conversation about that specifically. Why? Because it’s me – a woman. A woman they know. And because of whorephobia.

Whorephobia is the belief that certain types of sex work (camming, nude modeling, etc.) are effectually LESS demeaning and worthy of shame than other types of work (stripping, escorting, etc.) Whorephobia reinforces that a woman can maybe make money off her looks and sexuality – to a certain socially acceptable extent – but to be a WHORE is to be hanging from the lowest societal rung. Whorephobia is why society SLUT SHAMES any femme-presenting person for their attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that seek to liberate their sexualities and bodily autonomy.

Whorephobia is also why folks who have never been think burlesque shows are scandalous displays of salaciousness put on solely for male consumption – or they think that burlesque / all stripping is inherently exploitative, perpetuating the objectification that femmes already fight off daily. However, burlesque is so broad – and contemporary neo burlesque is very far from its traditional life form. The burlesque community is extremely queer and femme-focused, and audiences rarely contain stray creeps seeking a cheap thrill. “Exploitation” should not even enter the conversation; burlesque is all about autonomy and choice. Performers craft every component of their personas and acts. If anything, burlesque empowers those who participate to represent themselves exercising CHOICE in a world that objectifies bodies willy nilly.

Whorephobia is the belief that certain types of sex work (camming, nude modeling, etc.) are effectually LESS demeaning and worthy of shame than other types of work (stripping, escorting, etc.) Whorephobia reinforces that a woman can maybe make money off her looks and sexuality – to a certain socially acceptable extent – but to be a WHORE is to be hanging from the lowest societal rung. Whorephobia is why society SLUT SHAMES any femme-presenting person for their attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that seek to liberate their sexualities and bodily autonomy.

Whorephobia is also why folks who have never been think burlesque shows are scandalous displays of salaciousness put on solely for male consumption – or they think that burlesque / all stripping is inherently exploitative, perpetuating the objectification that femmes already fight off daily. However, burlesque is so broad – and contemporary neo burlesque is very far from its traditional life form. The burlesque community is extremely queer and femme-focused, and audiences rarely contain stray creeps seeking a cheap thrill. “Exploitation” should not even enter the conversation; burlesque is all about autonomy and choice. Performers craft every component of their personas and acts. If anything, burlesque empowers those who participate to represent themselves exercising CHOICE in a world that objectifies bodies willy nilly.

Whorephobia also reinforces that sex outside the confines of a romantic/procreative union is inherently bad and that anything with sex in it, including ART, is LESSER THAN. This is classist and ridiculous to me. We are AFRAID of the sex in creative works. Sex has always been integral to society’s interests and consuming it has existed since the dawn of time.

I see whorephobia and shaming around sex work as more of a reflection of society’s view of sexualized women. Whorephobia thus harms all women, not just sex workers.

My journey cultivating an entire practice (visual, curatorial, and performance) around sex work has been relatively brief in the span of a lifetime -- roughly seven years -- but it runs deep and is constantly changing. In the past year that Katina and I have been curating and producing our own monthly burlesque show, I've noticed my visual work has become more complex in response, for example.

I am always meeting new performers and sex workers who impart their own experiences and influences on me. And while I would say that my work explores topics like burlesque and sex work, ultimately it is about representation, community, and autonomy.

I see whorephobia and shaming around sex work as more of a reflection of society’s view of sexualized women. Whorephobia thus harms all women, not just sex workers.

My journey cultivating an entire practice (visual, curatorial, and performance) around sex work has been relatively brief in the span of a lifetime -- roughly seven years -- but it runs deep and is constantly changing. In the past year that Katina and I have been curating and producing our own monthly burlesque show, I've noticed my visual work has become more complex in response, for example.

I am always meeting new performers and sex workers who impart their own experiences and influences on me. And while I would say that my work explores topics like burlesque and sex work, ultimately it is about representation, community, and autonomy.

G: On your website I was struck by a quote of yours; “My self-portraits assert my own agency over how my body and sexual desires are represented” (McKeehen). Can you elaborate on the significance that one’s agency holds when telling the truths you do in your work as well as in sex work and burlesque at large?

EM: When we see images of “conventionally attractive” bodies, the surface rather than the subject takes priority. I was tested quite a bit when introducing photographs of myself and other glamorous people as my work in early grad school critiques. My images were regarded as boudoir photography and lingerie ads instead of as portraits.

I wanted viewers to engage with and wonder about the people in my images. Because they are interesting, complicated, wonderful people living daring lives. Because they are different. We are different. I’ve never considered myself a very conventional person, and yet my work was being perceived in the most conventional ways.

![Days of Rust, Counted Out in Loss, Snowmass, Colorado, Erica McKeehen, 2022]()

EM: When we see images of “conventionally attractive” bodies, the surface rather than the subject takes priority. I was tested quite a bit when introducing photographs of myself and other glamorous people as my work in early grad school critiques. My images were regarded as boudoir photography and lingerie ads instead of as portraits.

I wanted viewers to engage with and wonder about the people in my images. Because they are interesting, complicated, wonderful people living daring lives. Because they are different. We are different. I’ve never considered myself a very conventional person, and yet my work was being perceived in the most conventional ways.

In terms of speaking my truth by way of self-portraits; femme presenting bodies have rigid, patriarchal demands placed upon them to be pleasant and perfect, small and unassuming – and so a legion of accessible imagery exists depicting them in those ways. I believe most femmes cannot escape lifelong feelings of inadequacy thanks to patriarchy and capitalism.

Regarding representation, historically speaking, “sexy women” have typically been photographed by men, and so these depictions are engulfed in talk about male gaze and erogenous looking. Made by men, made for men. The PERSON in the photograph – and their personhood – are irrelevant. (I.E. My early grad school critiques.) I feel strongly that all of this – reductive, passive consideration – follows the old rubric of how society approaches depictions of femmes. I am a woman taking an image of myself. I’m not a lingerie model, and I’m not selling anything.

I ensure my voice is heard in my self-portraits by assuming the role of subject and author. My self-portraits are powerful acts of resistance against a lifetime of struggles with my body, disordered eating, chronic illness, self-harm, sexual violence, and emotional abuse.

GT: In an essay by Kristin Taylor for your thesis exhibition, Body Breeze Earth, it states that burlesque “dates back to the mid-19th century where performers then parodied popular theater or opera shows, mocking heroes like Shakespeare, while also foregoing the constrictive clothing of the era for more risqué skirts that put legs on full display” (Taylor). In your opinion, how do you feel burlesque has changed or stayed true to its origins if so?

EM: Burlesque’s exploration of identity, glamour, and performance has been a recurring conversation in the performance art, theater, and entertainment world for over 150 years, and burlesque is forever an art form that responds to the culture of its time throughout history (no matter the genre).

American burlesque is often seen as a genre of variety show with five distinguishing characteristics: minimal costuming, sexually suggestive dance, plot lines and staging, quick-witted humor, and short routines or sketches. In every genre, burlesque often comments about the times — a light irreverence to the status quo. The word derives from the Italian “burla,” a joke, ridicule, or mockery. In the beginning a certain level of literacy was assumed by audience members, as burlesque often made various high-brow references.

EM: Burlesque’s exploration of identity, glamour, and performance has been a recurring conversation in the performance art, theater, and entertainment world for over 150 years, and burlesque is forever an art form that responds to the culture of its time throughout history (no matter the genre).

American burlesque is often seen as a genre of variety show with five distinguishing characteristics: minimal costuming, sexually suggestive dance, plot lines and staging, quick-witted humor, and short routines or sketches. In every genre, burlesque often comments about the times — a light irreverence to the status quo. The word derives from the Italian “burla,” a joke, ridicule, or mockery. In the beginning a certain level of literacy was assumed by audience members, as burlesque often made various high-brow references.

Amidst the Great Depression, stock burlesque companies multiplied in major American cities, and in the 1930s and 40s, the art form drew viewers into clubs, music halls, and theaters with emboldened female performers outfitted with lush, colorful costumes, mood-appropriate music, and dramatic lighting. By this time, to fill theater seats (with mostly men) that were empty because of the advent of recent technologies, striptease became a regular component of the performances. The quality of striptease acts varied greatly. Some strippers, such as Gypsy Rose Lee and Sally Rand, imbued their performances with great artistry. But many others aimed only to titillate the sexual desires of the increasingly all-male audiences.

As performances became more salacious, local authorities increasingly challenged their right to exist. In Chicago and elsewhere, social reformers and child welfare advocates condemned the strip shows as bad moral influences and threats to the well-being of urban youth. Merchants often complained about burlesque theaters’ tendency to drive away customers from nearby businesses. Police periodically raided burlesque theaters and arrested the performers, charging them with unlawful or immoral conduct.

Today, burlesque is a blank slate. Sometimes it’s funny. Sometimes it’s sexy. Sometimes it’s highly choreographed and physical. Sometimes it’s conceptual with a slow build, props, and a storyline. Strippers incorporate burlesque into their pole routines and vice versa. Drag artists incorporate burlesque into their acts and vice versa. Yes, it can be titillating, but it’s thrilling for so many more reasons now than simply catching some skin. As I’ve noted, audiences are no longer male-dominated. Burlesque perhaps feels tame to a society that craves more and more explicitly.

However, if you think that people are not judged, demonized, taunted, disowned, or even fired for participating in tassel-twirling burlesque, you’re wrong. Members of my family and lifelong friends stopped talking to me the minute they caught wind of my burlesque involvement in 2017. I was questioned about it when I was fired from Starbucks (obviously, it was completely unrelated to the reasons that they ultimately gave for termination).

Burlesque performers like Rand were arrested for public indecency during their time because the world was not – and never has been – a stage for burlesque.

![Glove Peel (Obscura at Simone's), Erica McKeehen, 2022]()

However, if you think that people are not judged, demonized, taunted, disowned, or even fired for participating in tassel-twirling burlesque, you’re wrong. Members of my family and lifelong friends stopped talking to me the minute they caught wind of my burlesque involvement in 2017. I was questioned about it when I was fired from Starbucks (obviously, it was completely unrelated to the reasons that they ultimately gave for termination).

Burlesque performers like Rand were arrested for public indecency during their time because the world was not – and never has been – a stage for burlesque.