INTERVIEW WITH HANG ZHANG

By Rebecka Öhrström Kann 24/11/2023

Hang Zhang is an interdisciplinary artist based between London and Leeds whose work interrogates the hierarchical relationship between humans and non-humans across cultures through anthropomorphic humour. By employing storytelling as a method and building on her own perspective as a Chinese immigrant in the UK, Zhang’s practice looks at the construction of speciesism and Eurocentric narratives through engaging and interactive works that make space for non-human voices in institutional settings. We chatted about her transformative encounters with animals, her current research on camelids in Peruvian cultures and the symbolic use of alpacas by Chinese netizens, as well as the importance of play in her practice.By Rebecka Öhrström Kann 24/11/2023

Rebecka Ohrstrom Kann: How would you describe your work to someone who's never seen it before?

Hang Zhang: I think my projects differ quite a lot from each other, but they share a similarity in my interest to speak for the underprivileged or the understated in a humorous way. Underprivileged or understated in terms of some animals, but also some people, sometimes myself, depending on the context, because I don't think I'm underprivileged in all situations. For example, I grew up in a patriarchal household, and I didn't feel like I had enough freedom in terms of my body. My parents, especially my dad, judged my appearance, like my hair, my fashion style and even my body shape, in my teenage and young adult years. I didn't feel I had freedom in charge of my body, so I used getting tattoos (initially, hidden under the clothes) as a way to claim my body back. And going back to the underprivileged and understated, I’m interested in some cultures that aren’t represented enough on a global scale. Like I'm doing this PhD focusing on Peruvian culture, which is considered unfamiliar to a lot of people. But because I'm not from a South American background; I’m using my perspective, as a Chinese immigrant in the UK, to narrate my comparative understanding of these three cultures.

Hang Zhang: I think my projects differ quite a lot from each other, but they share a similarity in my interest to speak for the underprivileged or the understated in a humorous way. Underprivileged or understated in terms of some animals, but also some people, sometimes myself, depending on the context, because I don't think I'm underprivileged in all situations. For example, I grew up in a patriarchal household, and I didn't feel like I had enough freedom in terms of my body. My parents, especially my dad, judged my appearance, like my hair, my fashion style and even my body shape, in my teenage and young adult years. I didn't feel I had freedom in charge of my body, so I used getting tattoos (initially, hidden under the clothes) as a way to claim my body back. And going back to the underprivileged and understated, I’m interested in some cultures that aren’t represented enough on a global scale. Like I'm doing this PhD focusing on Peruvian culture, which is considered unfamiliar to a lot of people. But because I'm not from a South American background; I’m using my perspective, as a Chinese immigrant in the UK, to narrate my comparative understanding of these three cultures.

ROK: I'm also really intrigued by how you use stories as a means to center those narratives in your work. So, I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about the use of non-human narratives within your work and how you came to use storytelling in your practice.

HZ: I guess it's because I'm not from an artistic background, I just started to study art when I was, like, 25, so I lack traditional technical skills such as drawing and painting. I just use storytelling as my medium because I consider myself quite good at writing stories. It’s my value in making art. As an art recipient, I usually prefer narrative work to abstract work, abstract work with a background story that I know. As a result, I feel less confident in creating abstract work, so that's why I work quite straightforwardly. I make stuff most “non-art” people can understand. I actually have lots of like teenagers and kids who like my work [laughs]. And I’m happy about it because I think art belongs to everyone, instead of only for people with sophisticated tastes or art degrees.

ROK: I really like the storytelling aspect of your work, and like you said, it really makes it more approachable, it’s a familiar entrance. I actually didn't know that you started studying art later in life, how come you decided to study art? And also, what's your approach to art-making?

HZ: So the initial point when I started to study art, was because I was working at a design studio but I wasn't a designer, I worked with admin stuff. I was a little bit jealous of the people will knew how to design things and use the software, and initially, I wanted to be a designer, but shortly after that, I realised design at that moment didn’t fit many of my own values, so I ended up pursuing a different path, making visual art. And then, in terms of my current practice, I think I started to become interested in, like, animal studies around COVID lockdown, because I didn’t really have many interactions with humans. The animals I encountered in my life became really important because, at that time in the UK, we could go on, a daily walk, and you'd be in contact with some animals on the way. One time, I encountered a sheep who cuddled me, and it was very weird because sheep don't normally cover humans, but she just couldn't let me go.

I think just all the animals, including Sam[from Sam, the Flour Beetle, 2022], just changed my outlook. I think there are a number of contemporary visual artists doing projects that involve animals at the moment, but I don’t think animal studies from the perspective of the arts and humanities is saturated enough. I’ve always loved animals, but when I read John Berger’s Why Look at Animals?, and Peter Singer’s books on animal liberation, I realised that I loved looking at animals more than I loved the animal itself, and I felt guilty to be a speciesist. This is a term that Peter Singer coined in his works, which basically means that humans think they are better than other animals, but actually, everything should be equal on this earth, we are all earth made, were all made to share this globe, but it's not the case at the moment. So, I felt guilty to be part of the people who think humans are better than animals. I don’t literally think humans are better than animals, in fact, the other way round. But by still consuming animals, it automatically makes me a speciesist. However, because of my own issues, it's difficult for me to stop eating meat because of my upbringing, and the foods I used to eat when I grew up. And now I live in a foreign country, it just feels to me that if there's one connection for me to my home, it’s food. So, I tried to give up eating meat a few times, but it didn't work out in the end. I felt guilty about that. I'm finding a way to balance the guilt by using my voice as an artist to uplift animals in human culture and history. And the roles of llamas or alpacas in human history are the current subject.

HZ: I guess it's because I'm not from an artistic background, I just started to study art when I was, like, 25, so I lack traditional technical skills such as drawing and painting. I just use storytelling as my medium because I consider myself quite good at writing stories. It’s my value in making art. As an art recipient, I usually prefer narrative work to abstract work, abstract work with a background story that I know. As a result, I feel less confident in creating abstract work, so that's why I work quite straightforwardly. I make stuff most “non-art” people can understand. I actually have lots of like teenagers and kids who like my work [laughs]. And I’m happy about it because I think art belongs to everyone, instead of only for people with sophisticated tastes or art degrees.

ROK: I really like the storytelling aspect of your work, and like you said, it really makes it more approachable, it’s a familiar entrance. I actually didn't know that you started studying art later in life, how come you decided to study art? And also, what's your approach to art-making?

HZ: So the initial point when I started to study art, was because I was working at a design studio but I wasn't a designer, I worked with admin stuff. I was a little bit jealous of the people will knew how to design things and use the software, and initially, I wanted to be a designer, but shortly after that, I realised design at that moment didn’t fit many of my own values, so I ended up pursuing a different path, making visual art. And then, in terms of my current practice, I think I started to become interested in, like, animal studies around COVID lockdown, because I didn’t really have many interactions with humans. The animals I encountered in my life became really important because, at that time in the UK, we could go on, a daily walk, and you'd be in contact with some animals on the way. One time, I encountered a sheep who cuddled me, and it was very weird because sheep don't normally cover humans, but she just couldn't let me go.

I think just all the animals, including Sam[from Sam, the Flour Beetle, 2022], just changed my outlook. I think there are a number of contemporary visual artists doing projects that involve animals at the moment, but I don’t think animal studies from the perspective of the arts and humanities is saturated enough. I’ve always loved animals, but when I read John Berger’s Why Look at Animals?, and Peter Singer’s books on animal liberation, I realised that I loved looking at animals more than I loved the animal itself, and I felt guilty to be a speciesist. This is a term that Peter Singer coined in his works, which basically means that humans think they are better than other animals, but actually, everything should be equal on this earth, we are all earth made, were all made to share this globe, but it's not the case at the moment. So, I felt guilty to be part of the people who think humans are better than animals. I don’t literally think humans are better than animals, in fact, the other way round. But by still consuming animals, it automatically makes me a speciesist. However, because of my own issues, it's difficult for me to stop eating meat because of my upbringing, and the foods I used to eat when I grew up. And now I live in a foreign country, it just feels to me that if there's one connection for me to my home, it’s food. So, I tried to give up eating meat a few times, but it didn't work out in the end. I felt guilty about that. I'm finding a way to balance the guilt by using my voice as an artist to uplift animals in human culture and history. And the roles of llamas or alpacas in human history are the current subject.

ROK: How do you approach post-humanism through the medium of storytelling?

HZ: I don't think I have a project specifically using narratives as a means to approach post-humanism, but I agree with Donna Haraway’s idea of post-humanism and that we shouldn’t separate humans from non-humans. Posthumanism helps to break down the conventional social hierarchy, like deconstructing specialism and human gender roles, which Rosi Braidotti’s notion of cyborg feminism reflects on.

ROK: Could you talk a little bit about where you find inspiration and motivation for art making?

HZ: I think there are different motivations. One is more of practical motivation and the need to apply for grants, and funding, in order to survive as an artist. But then there’s also spiritual motivation. Like I think it’s the artist's responsibility to speak up for the people or the things they want to speak up for, and that’s the motivation. The Sam project kind of stemmed from that. During lockdown, my partner and I adopted a lab beetle. And we built a house for Sam, like a home, and made sure Sam was having a comfortable life…and I guess Sam had a comfortable life because they lived for almost two years whereas the average lifespan for a beetle is like nine months or something. But in retrospect…although me and my partner lived together, we couldn’t really see our friends, and we just really just wanted a pet. But we were living in a flat that didn’t allow for it, and also, for many other reasons, it just wasn't the right time to have a pet. And so we kind of funded our love for a potential pet to this small lab beetle. We named them Sam because we don't really know Sam's gender, and we don't want to assume it, so that's why Sam is the gender-neutral name we made for them. But we don't really know if they wanted us to “rescue” them in the beginning. Because Sam had a very long but also very lonely two-year life. They had no friends living with them. But we don't really know if this is a good thing or a bad thing. Because if we put another beetle in, we were worried they might fight and end up dying. But when I had Sam it just made me wonder why people overlook lab beetles. Like, when I would tell people that I had a flour beetle as a pet, they would be like, “How big is it?” or ‘What does it look like?” and I realized that people don’t really know these things. Even though they must have seen these species before, they pay like minimum attention to them. So it just made me think, is it because Sam is too small? That lab beetles are just too small, and that’s why people don't care about them. So, I made a giant and flexible beetle and attached it to myself to pretend that I am Sam. And that just feels so…like the feeling of wearing like a giant Sam on my back like that was so surreal. It made me feel like I broke the boundaries between humans and non/post-humans. Because Sam is a nonhuman animal, and I'm human, and the inflatable beetle is like a machine. So, me plus the inflatable beetle become kind of like a cyborg? Yeah, so I guess for me, making art is a way to reflect on things that regular people overlook, that’s the motivation.

ROK: It seems like it's also a lot of, like, self-reflection about your own personal life and what you're experiencing, like you rescued this beetle from your partner's lab, right? Initially, it was just a pet, but then it actually transitioned into becoming a central part of your practice. I also didn't know that the beetle is wearable, which is so cool, I think there is a real aspect of intimacy in that experience of the merging as well. I also want to ask you, because you grew up in China, but you're currently based in London. How have these places impacted or influenced the work you make?

HZ: So I was never officially an artist in China, but I’m sure I’d be making completely different work if I were an artist based in China- I would make work reflect more on life in China and problems I would encounter in China. Because I’m based in the UK, I lean on speaking for the immigrants in this social environment through artmaking.

Even though I’m based in the UK, my Chinese background and all the places I've been, the things I've seen, and the things I've done have all impacted my work. I always try to bring some of my Chinese philosophy to my practice, because I think is very overlooked in the West. I've seen Chinese philosophy labelled as other East Asian cultures in the West, and I get why the anti-Chinese stans in West media don’t make it easy to label things Chinese, and this makes me really sad. But I feel like the other like other artists with Chinese backgrounds in the West are making an effort to improve visibility, so hopefully, I can be one of them.

HZ: I don't think I have a project specifically using narratives as a means to approach post-humanism, but I agree with Donna Haraway’s idea of post-humanism and that we shouldn’t separate humans from non-humans. Posthumanism helps to break down the conventional social hierarchy, like deconstructing specialism and human gender roles, which Rosi Braidotti’s notion of cyborg feminism reflects on.

ROK: Could you talk a little bit about where you find inspiration and motivation for art making?

HZ: I think there are different motivations. One is more of practical motivation and the need to apply for grants, and funding, in order to survive as an artist. But then there’s also spiritual motivation. Like I think it’s the artist's responsibility to speak up for the people or the things they want to speak up for, and that’s the motivation. The Sam project kind of stemmed from that. During lockdown, my partner and I adopted a lab beetle. And we built a house for Sam, like a home, and made sure Sam was having a comfortable life…and I guess Sam had a comfortable life because they lived for almost two years whereas the average lifespan for a beetle is like nine months or something. But in retrospect…although me and my partner lived together, we couldn’t really see our friends, and we just really just wanted a pet. But we were living in a flat that didn’t allow for it, and also, for many other reasons, it just wasn't the right time to have a pet. And so we kind of funded our love for a potential pet to this small lab beetle. We named them Sam because we don't really know Sam's gender, and we don't want to assume it, so that's why Sam is the gender-neutral name we made for them. But we don't really know if they wanted us to “rescue” them in the beginning. Because Sam had a very long but also very lonely two-year life. They had no friends living with them. But we don't really know if this is a good thing or a bad thing. Because if we put another beetle in, we were worried they might fight and end up dying. But when I had Sam it just made me wonder why people overlook lab beetles. Like, when I would tell people that I had a flour beetle as a pet, they would be like, “How big is it?” or ‘What does it look like?” and I realized that people don’t really know these things. Even though they must have seen these species before, they pay like minimum attention to them. So it just made me think, is it because Sam is too small? That lab beetles are just too small, and that’s why people don't care about them. So, I made a giant and flexible beetle and attached it to myself to pretend that I am Sam. And that just feels so…like the feeling of wearing like a giant Sam on my back like that was so surreal. It made me feel like I broke the boundaries between humans and non/post-humans. Because Sam is a nonhuman animal, and I'm human, and the inflatable beetle is like a machine. So, me plus the inflatable beetle become kind of like a cyborg? Yeah, so I guess for me, making art is a way to reflect on things that regular people overlook, that’s the motivation.

ROK: It seems like it's also a lot of, like, self-reflection about your own personal life and what you're experiencing, like you rescued this beetle from your partner's lab, right? Initially, it was just a pet, but then it actually transitioned into becoming a central part of your practice. I also didn't know that the beetle is wearable, which is so cool, I think there is a real aspect of intimacy in that experience of the merging as well. I also want to ask you, because you grew up in China, but you're currently based in London. How have these places impacted or influenced the work you make?

HZ: So I was never officially an artist in China, but I’m sure I’d be making completely different work if I were an artist based in China- I would make work reflect more on life in China and problems I would encounter in China. Because I’m based in the UK, I lean on speaking for the immigrants in this social environment through artmaking.

Even though I’m based in the UK, my Chinese background and all the places I've been, the things I've seen, and the things I've done have all impacted my work. I always try to bring some of my Chinese philosophy to my practice, because I think is very overlooked in the West. I've seen Chinese philosophy labelled as other East Asian cultures in the West, and I get why the anti-Chinese stans in West media don’t make it easy to label things Chinese, and this makes me really sad. But I feel like the other like other artists with Chinese backgrounds in the West are making an effort to improve visibility, so hopefully, I can be one of them.

ROK: Now you're making work and research about camelids in South America. And I'm really curious how you came to if you could talk a little bit about that?

HZ: I thought there's some close connection between, like, my background and this animal because when I was a teenager, alpacas were like very new animals, like “exotic animals”, but in China. So alpacas were labelled as “the holy beast” by Chinese netizens in the early 2000s, but the Chinese nickname for alpaca sounds a lot like a really bad swearing word. So people use it as a means to express a political opinion and to say one thing when they can’t say things on the internet because of censorship by the Chinese government. And there are still some artists using alpacas, like Ai Weiwei or the Chinese word for alpaca on Twitter. Last year, during the COVID lockdown in China, some activists used the alpaca on Twitter, and in Shanghai protests, some people brought alpacas to the streets to protest because it functions like a political innuendo. So that was so it goes back to John Berger’s book Why Look at Animals? because people look at exotic animals, like alpacas or llamas, as fantasy creatures rather than just themselves. And then, during COVID in the UK, we tried doing some outdoorsy things, but we’re not really outdoorsy people. So we tried a llama trek a few times where you just walk a llama on the farm. And that just made me think of how we use animals as support, especially ungulate animals for like horse riding and those sorts of things, which is a very Western concept. Because in Peru, you don’t really walk your alpacas for fun, they have a more agricultural function. So that made me reflect on how different cultures see animals, and then how they see animals from a foreign background, and how animals like alpacas or llamas can have such different functions and representations across cultures, which is very interesting to me.

ROK: Who, or what are some of the influences to help you evolve the visual language of your work?

HZ: Definitely different things. Early on, I wasn't as inspired by other artists until maybe the past two years, when I feel like they’ve had a bigger impact on me, in terms of technique and other things. Also, some people I mentioned earlier in the interview, philosophers like Donna Haraway, and Rosi Braidotti, have been important, and just a lot of things I’ve seen in my life make me feel like I need to use my artist's voice to like express this thing. And my artist friends that are in different stages of their, careers; some of them, are considered successful and some of them are emerging, like myself. The way we think of the world and the work we produce, I think, all have like a reflection on each of us.

HZ: I thought there's some close connection between, like, my background and this animal because when I was a teenager, alpacas were like very new animals, like “exotic animals”, but in China. So alpacas were labelled as “the holy beast” by Chinese netizens in the early 2000s, but the Chinese nickname for alpaca sounds a lot like a really bad swearing word. So people use it as a means to express a political opinion and to say one thing when they can’t say things on the internet because of censorship by the Chinese government. And there are still some artists using alpacas, like Ai Weiwei or the Chinese word for alpaca on Twitter. Last year, during the COVID lockdown in China, some activists used the alpaca on Twitter, and in Shanghai protests, some people brought alpacas to the streets to protest because it functions like a political innuendo. So that was so it goes back to John Berger’s book Why Look at Animals? because people look at exotic animals, like alpacas or llamas, as fantasy creatures rather than just themselves. And then, during COVID in the UK, we tried doing some outdoorsy things, but we’re not really outdoorsy people. So we tried a llama trek a few times where you just walk a llama on the farm. And that just made me think of how we use animals as support, especially ungulate animals for like horse riding and those sorts of things, which is a very Western concept. Because in Peru, you don’t really walk your alpacas for fun, they have a more agricultural function. So that made me reflect on how different cultures see animals, and then how they see animals from a foreign background, and how animals like alpacas or llamas can have such different functions and representations across cultures, which is very interesting to me.

ROK: Who, or what are some of the influences to help you evolve the visual language of your work?

HZ: Definitely different things. Early on, I wasn't as inspired by other artists until maybe the past two years, when I feel like they’ve had a bigger impact on me, in terms of technique and other things. Also, some people I mentioned earlier in the interview, philosophers like Donna Haraway, and Rosi Braidotti, have been important, and just a lot of things I’ve seen in my life make me feel like I need to use my artist's voice to like express this thing. And my artist friends that are in different stages of their, careers; some of them, are considered successful and some of them are emerging, like myself. The way we think of the world and the work we produce, I think, all have like a reflection on each of us.

ROK: You use humour quite a bit in your work, either with Sam, the Red Flour Beetle (2022) and sort of the absurdity of blowing up this insect that is normally the size of a raisin or in your work Cat Tattooing Cat (2022), which seems like its a nod to the literary tradition of the fable and genre’s use of Anthropomorphism.

HZ: Yeah, I try to be humorous with my work. Obviously, artists have different approaches. Some artists want the visitor or the audience to feel uncomfortable, but I generally want my audience to have a good time when they see my work because I don't consider myself as a very happy person, because of lots of things probably, which made me want my practice to be a fun part of my life. And also a fun part of people's lives. I made lots of works for the project called Lady Accessory (2022), which is based on the sheep I mentioned earlier that I met on that walk who just cuddled me. And then she had, like, a leaf on her body which was very pretty, so I call her “lady accessory” and made a dress-up game based on a game I used to play as a kid with different accessories for the sheep, so people can dress up the sheep. It’s been really popular among kids. I’ve exhibited it a few times in different venues and the kids are really into it but their parents are like, “Come on, we need to go home!” [laughs]. I think if I give someone a good time, no matter how old they are, I consider that work successful.

ROK: I feel like that’s such a good motto like you just want people to have a good time, and I can really see that playful energy in your work. To finish, what's next for you?

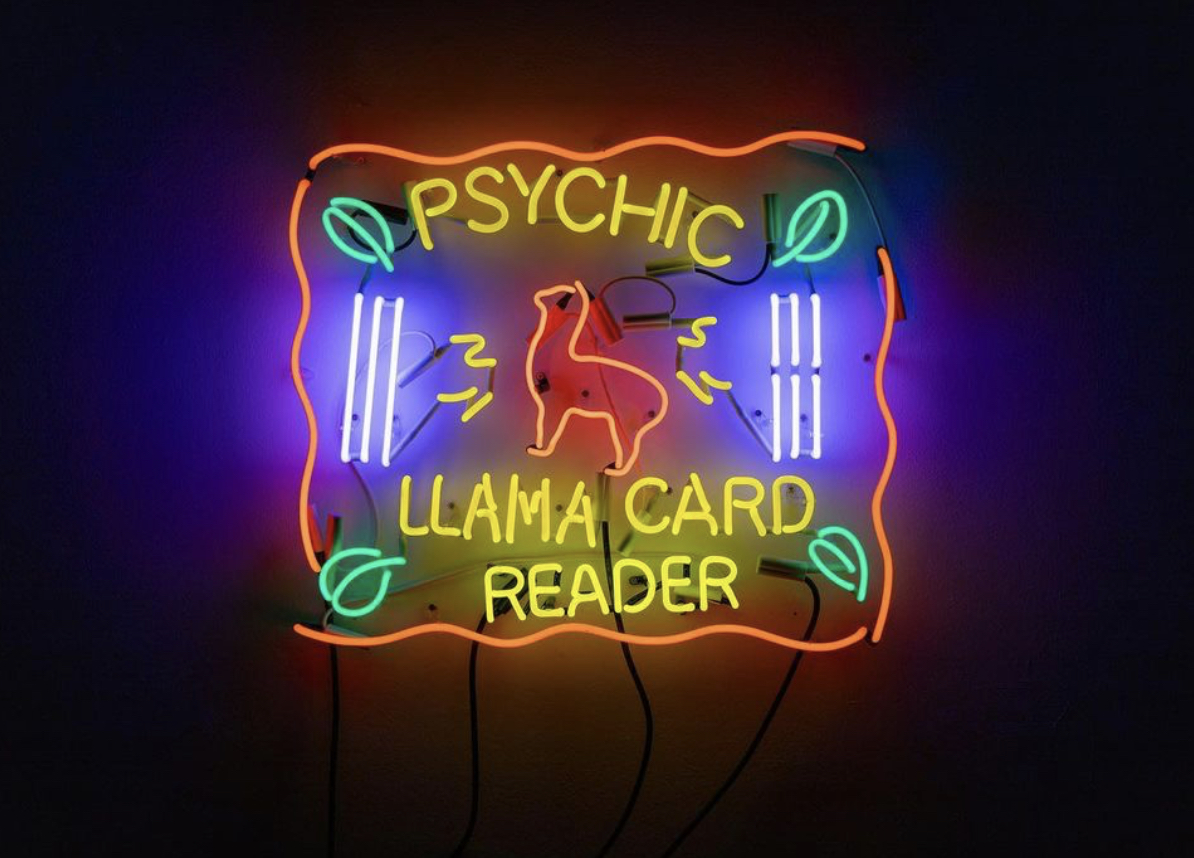

HZ: I’m about halfway through my PhD project. In the first year of my PhD, I did the llama cart deck, which is like a divination cart influenced by the camelid in Peruvian culture, and I use it as a tarot card to predict people's fortune, to make people understand what they actually want in life. And when people ask me questions, some people say that the llama cards are actually very accurate. I don't know if it's just literally anything magical about this llama cart, or if using the cards just helps them to understand what they really want in their life. Yeah, so that's this thing I did for my first year. I think next, I want to make some ceramics inspired by different Incan cultures or pre-Incan cultures but also Western culture. Like a cross-culture twist on Western ceramic making and Chinese ceramic-making. Some people call them like pseudo artefacts, but I don't know if it's the right word to use. I'm creating some things that look like artefacts but that aren’t really artefacts from any culture.