INTERVIEW WITH JAN SIMONDS

by Giselle Torres

18/2/2024

Giselle Torres: Jan, to get started it would be great if you could tell us about your practice and how you came around to finding art and where you are now in terms of your practice?

Jan Simonds: Yeah, sure. I was always naturally making stuff (watercolors, my own comics, drawings mostly) but I experienced a degree of shame or discomfort around it. I was always an odd kid in elementary school because of my name, I had a bowl haircut and was bullied for being gay before I even realized it, among other factors that made me a lot more inhibited and negative. At age ten, I moved to Boston from California and I met my friend Nihil. Initially we were very resistant towards each other's personalities, but we found out we have a lot in common. He has artist parents and we ended up going to all these independent music shows together. I was really tall and he was really short and so I was somewhat of a bodyguard. I was getting a lot of social cultural awareness from these experiences that I wouldn’t have had otherwise. It invigorated me and created underlying creative impulses, and it forced me to expand my thinking.

A lot of my creative energy now really comes from that period of time, and I was mostly thinking about music. The times I was drawing were when we had paper around the shows or we would be at his apartment and draw together for fun. The decision to develop it into a professional pursuit was because I was 15 or 16 during New Year’s and thinking to myself, “I hate science, I’m fine at history, I’m good at English. I can’t think of a single school subject that I want to make into a career other than art so I guess I have to dedicate myself to it”. From that point on I was a lot more intentional about trying to accomplish something.

Where I’m at now, I feel really lucky and privileged. I used to experience a significant amount of self-doubt and self-criticism. I used that as an engine to work harder but once you receive validation through working in that method, even though other people don't see it, it is reinforced. I am able to see how I make things differently now. In the recent past, I was a lot more pessimistic, safeguarded and judgmental, but after putting attention into what I find valuable, eliminating other people’s concerns became a lot easier. I am focused on creating drawings with genuine intention so it makes the praise all the more impactful as well. I’m done playing a mental game of Tetris against the broader fine art scene to find where I fit in.

Jan Simonds: Yeah, sure. I was always naturally making stuff (watercolors, my own comics, drawings mostly) but I experienced a degree of shame or discomfort around it. I was always an odd kid in elementary school because of my name, I had a bowl haircut and was bullied for being gay before I even realized it, among other factors that made me a lot more inhibited and negative. At age ten, I moved to Boston from California and I met my friend Nihil. Initially we were very resistant towards each other's personalities, but we found out we have a lot in common. He has artist parents and we ended up going to all these independent music shows together. I was really tall and he was really short and so I was somewhat of a bodyguard. I was getting a lot of social cultural awareness from these experiences that I wouldn’t have had otherwise. It invigorated me and created underlying creative impulses, and it forced me to expand my thinking.

A lot of my creative energy now really comes from that period of time, and I was mostly thinking about music. The times I was drawing were when we had paper around the shows or we would be at his apartment and draw together for fun. The decision to develop it into a professional pursuit was because I was 15 or 16 during New Year’s and thinking to myself, “I hate science, I’m fine at history, I’m good at English. I can’t think of a single school subject that I want to make into a career other than art so I guess I have to dedicate myself to it”. From that point on I was a lot more intentional about trying to accomplish something.

Where I’m at now, I feel really lucky and privileged. I used to experience a significant amount of self-doubt and self-criticism. I used that as an engine to work harder but once you receive validation through working in that method, even though other people don't see it, it is reinforced. I am able to see how I make things differently now. In the recent past, I was a lot more pessimistic, safeguarded and judgmental, but after putting attention into what I find valuable, eliminating other people’s concerns became a lot easier. I am focused on creating drawings with genuine intention so it makes the praise all the more impactful as well. I’m done playing a mental game of Tetris against the broader fine art scene to find where I fit in.

GT: Have you been met with any challenges relating to that early on decision of dedicating yourself to your art practice?

JS: Oh, of course. Internal mostly. Even though my mom emigrated from Slovakia, before I wanted to be a visual artist I wanted to be an actor as a kid, and that was okay at the time. As I got older and learned more about the arts, my thoughts on it became complex. I would go to Slovakia every summer, which led to my specific awareness of class, within and outside of my family. I began feeling a lot of shame for wanting to be an artist because I know how unsustainable it can be and how it’s not an option for some brilliant creative people without funds. There’s a difference in feeling like creative pursuits are within your reach because of your environment. I felt a bit of a twinge about my continued interest, but I was never outwardly told by family members that I shouldn’t or can’t do this. My mom supported me in going to pre-college at RISD and in going to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. When I was in Highschool, she was interested in having me sign up for art classes and I would say no. Simultaneously, I was being influenced by the punk kids I would hang out with who gave me an early introduction to the class relationships within art. I was aware of the unique characteristics that can just come through your hand. I wanted to maintain and work through that more so than learning other people’s methods on how to create.

GT: How do you explore a sense of self in your work?

JS: For me, the intent of my work is personal evolution. I’m trying to approach challenging, some traumatic, moments in my life that I’ve attempted to move on from without actually thinking through in order to understand their impact. Trying to integrate instead of continuing to run. indignity, my first solo exhibition was about a layered type of internal forgiveness I felt I had to give to myself and my family. I became really insular and dark during my teens because of opinions and actions they may not have realized were causing me grief. The dominant cultural Catholicism in Slovakia and the lack of any openly queer people did have an impact on me, my family is from quite a rural, conservative place. Even when there were queer people I met through family in the U.S., prejudicial private utterances pierced my thoughts. I remember having teachers in college who would try to encourage me to make work about those aspects of myself, sexuality specifically, and I did but in a very coded way that I didn’t speak about and most people didn’t pick up on. I didn’t really want them to because I was fearful and considerate about my family seeing it, I worried about what they would think of me, and I couldn’t tell if my teachers’ advice was genuine or telling me something I could exploit.

It took a huge amount of confidence to be like, “screw it, I’m going to make these images I want to make.” Some of them are of naked men kissing and embracing, and I thought if I lost favor with any family members I was to accept that and move on. I decided that I would not continue to let anxiety and fear rule over how I present. But, that was tough because my family in Slovakia are so loving, they are my closest family even though they are the furthest away from me and I didn’t want to lose that. I avoid making work that is judgmental or blames people, because I know them to be generous and kind. My issue is with beliefs they were brought into. I focus on how I was impacted, the resulting alienation I feel between Slovakia and the U.S., and a complicated relationship with sexuality, tradition, and religion.

JS: Oh, of course. Internal mostly. Even though my mom emigrated from Slovakia, before I wanted to be a visual artist I wanted to be an actor as a kid, and that was okay at the time. As I got older and learned more about the arts, my thoughts on it became complex. I would go to Slovakia every summer, which led to my specific awareness of class, within and outside of my family. I began feeling a lot of shame for wanting to be an artist because I know how unsustainable it can be and how it’s not an option for some brilliant creative people without funds. There’s a difference in feeling like creative pursuits are within your reach because of your environment. I felt a bit of a twinge about my continued interest, but I was never outwardly told by family members that I shouldn’t or can’t do this. My mom supported me in going to pre-college at RISD and in going to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. When I was in Highschool, she was interested in having me sign up for art classes and I would say no. Simultaneously, I was being influenced by the punk kids I would hang out with who gave me an early introduction to the class relationships within art. I was aware of the unique characteristics that can just come through your hand. I wanted to maintain and work through that more so than learning other people’s methods on how to create.

GT: How do you explore a sense of self in your work?

JS: For me, the intent of my work is personal evolution. I’m trying to approach challenging, some traumatic, moments in my life that I’ve attempted to move on from without actually thinking through in order to understand their impact. Trying to integrate instead of continuing to run. indignity, my first solo exhibition was about a layered type of internal forgiveness I felt I had to give to myself and my family. I became really insular and dark during my teens because of opinions and actions they may not have realized were causing me grief. The dominant cultural Catholicism in Slovakia and the lack of any openly queer people did have an impact on me, my family is from quite a rural, conservative place. Even when there were queer people I met through family in the U.S., prejudicial private utterances pierced my thoughts. I remember having teachers in college who would try to encourage me to make work about those aspects of myself, sexuality specifically, and I did but in a very coded way that I didn’t speak about and most people didn’t pick up on. I didn’t really want them to because I was fearful and considerate about my family seeing it, I worried about what they would think of me, and I couldn’t tell if my teachers’ advice was genuine or telling me something I could exploit.

It took a huge amount of confidence to be like, “screw it, I’m going to make these images I want to make.” Some of them are of naked men kissing and embracing, and I thought if I lost favor with any family members I was to accept that and move on. I decided that I would not continue to let anxiety and fear rule over how I present. But, that was tough because my family in Slovakia are so loving, they are my closest family even though they are the furthest away from me and I didn’t want to lose that. I avoid making work that is judgmental or blames people, because I know them to be generous and kind. My issue is with beliefs they were brought into. I focus on how I was impacted, the resulting alienation I feel between Slovakia and the U.S., and a complicated relationship with sexuality, tradition, and religion.

GT: How did you feel once you had begun to create work that was centered around forgiveness and pushing through those constraints of familial expectation? Did it feel freeing?

JS: Yes. It was honestly really strange and difficult to get there because I was isolating myself while making that work. I didn’t want any input so I took a year off of social media. I didn’t want to be seen and I didn’t want to socialize. I wanted to create a situation where my direct and truthful relationships with friends and colleagues would become evident by the fact that I was only having one to one communications, whether they came to me or vice-versa. Fast forwarding to the following October, I felt so much appreciation working with Turley Gallery and being with Sam Cockrell and Emily Janowick who facilitated part of my stay in New York. It was jarring, in a good way, because there were other times when past work was well received that didn’t impact me in the same way. I was working through barriers of fear that I wasn’t talking about. Getting to the other side of that year-long process was wild because I didn't have to second guess my relationships anymore.

JS: Yes. It was honestly really strange and difficult to get there because I was isolating myself while making that work. I didn’t want any input so I took a year off of social media. I didn’t want to be seen and I didn’t want to socialize. I wanted to create a situation where my direct and truthful relationships with friends and colleagues would become evident by the fact that I was only having one to one communications, whether they came to me or vice-versa. Fast forwarding to the following October, I felt so much appreciation working with Turley Gallery and being with Sam Cockrell and Emily Janowick who facilitated part of my stay in New York. It was jarring, in a good way, because there were other times when past work was well received that didn’t impact me in the same way. I was working through barriers of fear that I wasn’t talking about. Getting to the other side of that year-long process was wild because I didn't have to second guess my relationships anymore.

The work became more genuine and so did the responses to it. It eliminated a lot of problems I inadvertently caused by trying to accommodate myself for perceived judgment that has nothing to do with why I actually make art. The result was validating and it has made me more consistent in my practice. I don’t have the same nagging self consciousness around how I’m perceived because now my goal is to create a window for people to see how I am perceiving the world.

GT: To hear this makes me so happy for you! You strove to show your most authentic self through your work even though it was daunting and now making your work that highlights this. I definitely feel like your experience is something that people can relate to as well. People can connect with your work and get so much more out of it when it does not have those subliminal messages. And once you removed those and were upfront about your content the people who appreciate that kind of work found you and I am very happy you have gotten to this place!

GT: To hear this makes me so happy for you! You strove to show your most authentic self through your work even though it was daunting and now making your work that highlights this. I definitely feel like your experience is something that people can relate to as well. People can connect with your work and get so much more out of it when it does not have those subliminal messages. And once you removed those and were upfront about your content the people who appreciate that kind of work found you and I am very happy you have gotten to this place!

JS: I appreciate that. By the same token, it made me realize all the anger I can enact out of fear and scarcity. It has made me confront all aspects of myself and try to prevent negative patterns from recurring. So, I am seeking out better environments that are conducive to my mental health and my ability to be genuine and creative. That is something you can’t really teach people and the process is so individual. I think finding where you best fit is something that should be prioritized when learning how to be an artist, finding what sustains you independently instead of letting your surroundings dictate that for you. To me, being an artist is a wholly holistic pursuit, in the making process too. The way I really learned to draw was by realizing there's a degree of physical satisfaction I need to enjoy the experience. All of my technical choices and other elements come from my concern over if it is gratifying physically and visually. I prefer not to paint because the process isn’t that way for me. The results can be great but I haven’t found a process of doing it that makes me want to return the same way I feel with drawing. I’ve always loved the immediacy of drawing, how easy it is to store, the impact of contrast, and the mark making of it.

I don't want to feel removed from the painting, and sometimes I feel like the extension of the brush removes me from the impact of the bristles on the surface. Whereas with a pencil, I feel the graphite going into the paper; I feel the mark being made. If I can feel that, I can see myself in it and it means more when someone likes it because I have a physical reference for the work I put in. Like when I carve my frames, I've accidentally cut my hands so many times doing so, I feel and see the completed works in multiple ways.

GT: Something I really admire about your hand-carved frames is that you can tell they were made by the same hands that made the drawings in terms of gestures the hand has made and technique and style. Where and when did you learn to carve?

JS: Thank you so much! I taught myself actually. The first time I made a frame was in my last studio art class in winter of 2020 into 2021. I wanted to try it because I had a body of work where I was drawing on legal pad paper and I wanted to make a frame that would bring out the context of the images. The references I was making in that work really went over people’s heads because they were so specific and European. And it’s understandable that people may not have understood that if they are not familiar with Czech and Slovak cultural motifs. To some, it looked cartoonish. I was using legal pad paper because I was initially making sketches for paintings and I didn’t want to use expensive paper. I also wanted to explore themes I was concerned people wouldn’t be receptive to, which are present in my drawings now, but that I still really wanted to make. That surface removed the pressure of putting all of my risks, that felt so personal, on expensive materials. I wanted to sidestep that overly-encouraged element of art school, and in doing so started to find what I honestly want to present.

JS: Thank you so much! I taught myself actually. The first time I made a frame was in my last studio art class in winter of 2020 into 2021. I wanted to try it because I had a body of work where I was drawing on legal pad paper and I wanted to make a frame that would bring out the context of the images. The references I was making in that work really went over people’s heads because they were so specific and European. And it’s understandable that people may not have understood that if they are not familiar with Czech and Slovak cultural motifs. To some, it looked cartoonish. I was using legal pad paper because I was initially making sketches for paintings and I didn’t want to use expensive paper. I also wanted to explore themes I was concerned people wouldn’t be receptive to, which are present in my drawings now, but that I still really wanted to make. That surface removed the pressure of putting all of my risks, that felt so personal, on expensive materials. I wanted to sidestep that overly-encouraged element of art school, and in doing so started to find what I honestly want to present.

GT: You mentioned that these drawings were intended to be sketches for a more finalized goal in mind. On your website, I noticed you have them displayed with all your other work. Do you now feel differently about that body of work in terms of if they are a finalized thought in and of themselves?

JS: Yes, definitely. They became their own body of work that I nurtured, they are a part of my artistic pathway and I see them as meaningful stepping stones that led me to having studio visits and making connections I didn’t know I could make at that time in school. Reflecting back, I can see how much I have grown into myself. I was exploring how to communicate parts of myself with aspects of Slovakian culture, however, the dissonance between my personal discomfort with returning to Slovakia when I accepted my sexuality and trying to appreciate the culture was driving a wedge in my ability to make that work. I was trying to reinterpret cultural imagery I still like but I couldn't help but feel confronted by the fact that I didn’t know the average person there would like me for who I fully am; regardless of what we share. I was trying my best to be honest about just one part of me while removing the other so I view that work as an attempt to compromise. Now, I feel I’m making work that doesn’t compromise for anyone and I’m going to try to keep it that way.

JS: Yes, definitely. They became their own body of work that I nurtured, they are a part of my artistic pathway and I see them as meaningful stepping stones that led me to having studio visits and making connections I didn’t know I could make at that time in school. Reflecting back, I can see how much I have grown into myself. I was exploring how to communicate parts of myself with aspects of Slovakian culture, however, the dissonance between my personal discomfort with returning to Slovakia when I accepted my sexuality and trying to appreciate the culture was driving a wedge in my ability to make that work. I was trying to reinterpret cultural imagery I still like but I couldn't help but feel confronted by the fact that I didn’t know the average person there would like me for who I fully am; regardless of what we share. I was trying my best to be honest about just one part of me while removing the other so I view that work as an attempt to compromise. Now, I feel I’m making work that doesn’t compromise for anyone and I’m going to try to keep it that way.

GT: Yes, when I look at the work you have made from 2020 to now, it is very evident that you have now found a consistent visual voice that echoes the essences of your work from the past but now it seems like those ideas are, like you said, is uncomprimisingly you which is wonderful. What are some influences that have impacted the visual language of your work?

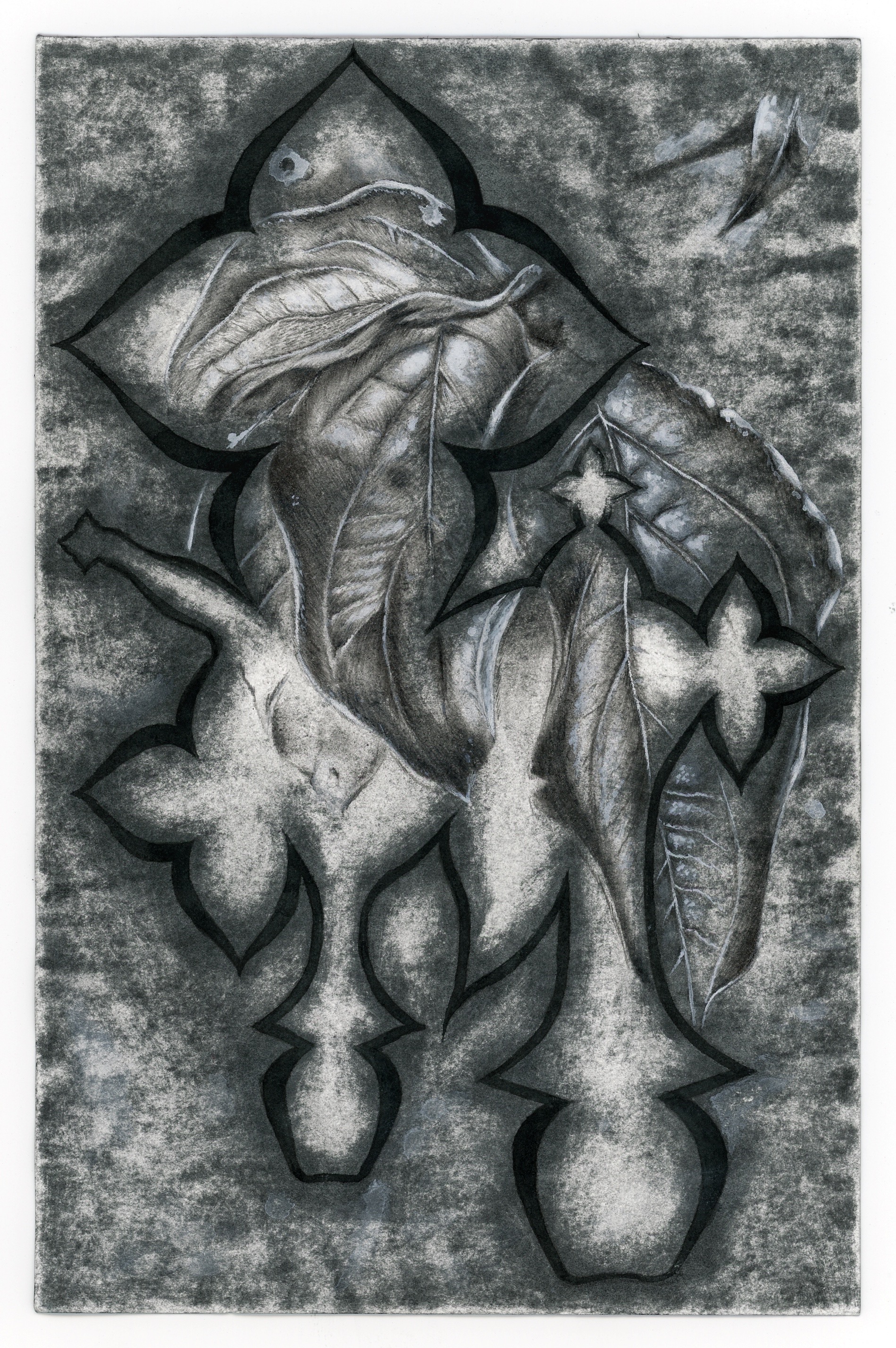

JS: Music was huge and well, it always is for me. I started reconnecting with hardcore music around the summer of 2022. I stopped listening to heavy music during my time in college because there were some behavioral things I wanted to work on and I thought the music was potentially enabling those problems. Once I reconnected with it, it brought out all this buried frustration and made me realize that I want to do what they're doing, in terms of working with and through anger. I wanted to channel it away from a negative impact and turn it into a personal release and freedom. I want to use that approach to get to the other side instead of just bottling it up. Bands like Thursday, Touche Amore, Militarie Gun, and other really good melodic hardcore bands made me feel okay with being angry. The impact of this on the aesthetic shift began with me being more abrasive with the paper.

My process now has several reductive and additive techniques when toning the paper and then removing that tone to draw. It requires a lot of physical action and digging into it, removing parts of the material to create that look. Similar to hand-carving my frames, the physicalization allows me to express these emotions that often in the art world are deemed as ugly, uncouth, or inappropriate. There is a general consensus that observably-passive is somehow better and I am not a passive person. I am very straightforward and I say what I think. So, my practice needs to account for that as well. I think, if anything, where I am now is all about the emphasis of that. These images are high contrast and I’ve always liked tight designs, but I’ve also become a lot looser in the rendering process and I really enjoy that.

I have opened myself up more to experimenting with different levels of visual dynamics from changing the design, tone, texture, and changing compositional styles so they all exist in a body of work but I’m pushing what that can look like so I don’t feel static. I like to iterate and continue to make new stuff. I think there’s a tendency for artists to lock into a visual method that works and the business of being an artist can put us in that position but I simply won’t do that unless I choose to. So, if I do the same thing repeatedly, I like to and I want to, and I feel total agency if I ever decide to change my mind.

JS: Music was huge and well, it always is for me. I started reconnecting with hardcore music around the summer of 2022. I stopped listening to heavy music during my time in college because there were some behavioral things I wanted to work on and I thought the music was potentially enabling those problems. Once I reconnected with it, it brought out all this buried frustration and made me realize that I want to do what they're doing, in terms of working with and through anger. I wanted to channel it away from a negative impact and turn it into a personal release and freedom. I want to use that approach to get to the other side instead of just bottling it up. Bands like Thursday, Touche Amore, Militarie Gun, and other really good melodic hardcore bands made me feel okay with being angry. The impact of this on the aesthetic shift began with me being more abrasive with the paper.

My process now has several reductive and additive techniques when toning the paper and then removing that tone to draw. It requires a lot of physical action and digging into it, removing parts of the material to create that look. Similar to hand-carving my frames, the physicalization allows me to express these emotions that often in the art world are deemed as ugly, uncouth, or inappropriate. There is a general consensus that observably-passive is somehow better and I am not a passive person. I am very straightforward and I say what I think. So, my practice needs to account for that as well. I think, if anything, where I am now is all about the emphasis of that. These images are high contrast and I’ve always liked tight designs, but I’ve also become a lot looser in the rendering process and I really enjoy that.

I have opened myself up more to experimenting with different levels of visual dynamics from changing the design, tone, texture, and changing compositional styles so they all exist in a body of work but I’m pushing what that can look like so I don’t feel static. I like to iterate and continue to make new stuff. I think there’s a tendency for artists to lock into a visual method that works and the business of being an artist can put us in that position but I simply won’t do that unless I choose to. So, if I do the same thing repeatedly, I like to and I want to, and I feel total agency if I ever decide to change my mind.

GT: It seems like your practice is definitely still a mode of cathartic release for you, would you say that is accurate?

JS: It’s the one time I can just be myself and my whole life I’ve felt that I had to care about other people’s perception of me, in America and in Slovakia. I felt that I had to accommodate for being perceived as being foreign when I was younger and in Slovakia for my sexuality and being potentially seen as privileged because I am currently the only member of my Slovak family to be born and raised here, and I don’t speak the language as well as they do. It is still a very important part of who I am and there are cultural things I want to keep in my life, sometimes I wonder if that is in conflict with my identity. I have a difficult time trying to reconcile who I am because of the world around me. My art is the one moment that I can just be all of those things at once and I don’t have to care.

GT: So, a lot of your work is centered around your experiences and life and heritage. What do you hope people take away from your work?

JS: I think that so much of how I communicate occurs subconsciously. I make a conscious effort to make drawings that are visually appealing within my tastes as objectively strong as possible. I consider the composition and all the formal elements of it, thinking about how the viewer will see the face of the work. The content of it and however it resonates, will inevitably vary from person to person. I feel that I have been really lucky because the intent of the work has come across without me feeling I need to emphasize it more through something like text or titles. I participated in a talk for my show and the main-space two person show Care, of works by Tamara Zahaykevich and Dana Piazza. The moderator, Anne Schaffer, artist, curator, and facilitator, wrote really insightful questions for everyone.

At that moment, I was so struck by how much information she took away from my work. I know how much I get out of making it and how much of me is in it, but the fact that we had never met before and she was asking me these insightful questions in front of these other people felt really nice. I feel like as soon as you try to control that, how your work communicates, you can lose it. I try not to think about it too much and I try to stay in the most pure elements of the creative process. And since I am receiving the response that I have hoped for, it is incredibly encouraging. I was super insecure about my ability to make art when I was younger because Nihil guided me to the punk shows. I always saw him as bringing me into a world of creativity, he was always a blueprint to me. Even when I did RISD pre-college I felt I was the worst at drawing from life in the course out of everybody. I didn’t come in with a bunch of natural ability in that way. I just wanted to be an artist and I couldn't stop myself.

GT: Yeah, that must have felt so affirming to be seen so clearly at your first solo show, “indignity” at Turley Gallery!

JS: Yeah, definitely. And this is super personal stuff so there’s an added level to it. I am working on other potential opportunities that I'm excited for, I really like the drawings I have planned. Going back to ideas of playing with dynamics and form, these drawings continue where I’ve been but I’m also pushing what I can do with composition and design in ways I think are exciting and new for me.

JS: It’s the one time I can just be myself and my whole life I’ve felt that I had to care about other people’s perception of me, in America and in Slovakia. I felt that I had to accommodate for being perceived as being foreign when I was younger and in Slovakia for my sexuality and being potentially seen as privileged because I am currently the only member of my Slovak family to be born and raised here, and I don’t speak the language as well as they do. It is still a very important part of who I am and there are cultural things I want to keep in my life, sometimes I wonder if that is in conflict with my identity. I have a difficult time trying to reconcile who I am because of the world around me. My art is the one moment that I can just be all of those things at once and I don’t have to care.

GT: So, a lot of your work is centered around your experiences and life and heritage. What do you hope people take away from your work?

JS: I think that so much of how I communicate occurs subconsciously. I make a conscious effort to make drawings that are visually appealing within my tastes as objectively strong as possible. I consider the composition and all the formal elements of it, thinking about how the viewer will see the face of the work. The content of it and however it resonates, will inevitably vary from person to person. I feel that I have been really lucky because the intent of the work has come across without me feeling I need to emphasize it more through something like text or titles. I participated in a talk for my show and the main-space two person show Care, of works by Tamara Zahaykevich and Dana Piazza. The moderator, Anne Schaffer, artist, curator, and facilitator, wrote really insightful questions for everyone.

At that moment, I was so struck by how much information she took away from my work. I know how much I get out of making it and how much of me is in it, but the fact that we had never met before and she was asking me these insightful questions in front of these other people felt really nice. I feel like as soon as you try to control that, how your work communicates, you can lose it. I try not to think about it too much and I try to stay in the most pure elements of the creative process. And since I am receiving the response that I have hoped for, it is incredibly encouraging. I was super insecure about my ability to make art when I was younger because Nihil guided me to the punk shows. I always saw him as bringing me into a world of creativity, he was always a blueprint to me. Even when I did RISD pre-college I felt I was the worst at drawing from life in the course out of everybody. I didn’t come in with a bunch of natural ability in that way. I just wanted to be an artist and I couldn't stop myself.

GT: Yeah, that must have felt so affirming to be seen so clearly at your first solo show, “indignity” at Turley Gallery!

JS: Yeah, definitely. And this is super personal stuff so there’s an added level to it. I am working on other potential opportunities that I'm excited for, I really like the drawings I have planned. Going back to ideas of playing with dynamics and form, these drawings continue where I’ve been but I’m also pushing what I can do with composition and design in ways I think are exciting and new for me.

GT: Well, I am very excited to see that! The show at Turley Gallery was your first solo show so I was wondering what advice you have to those who are looking to get their work in a solo show? Were there any challenges you had to face in getting into contact with them or anything of the sort?

JS: It’s kind of a unique situation. So, my grandmother passed away in the fall of 2021 and I was working on an etching with Pigeonhole Press. The etching was a cross with eyes superimposed in front of it, that led me down the rabbit hole of wanting to make more cross imagery. When I was visiting her before she passed, I saw a cross in a museum in Bardejov that really spoke to me. It was a medieval type of hand-held cross that would be used in religious ceremonies. It inspired the first drawing I made using this additive and reductive process. I made four of them and posted three online, and after I posted the third one I found Turley Gallery. We had a visit over Zoom and it just went from there. Ryan Turley has facilitated a fantastic community in Hudson. He's an artist as well and his care for other artists really comes through in how he does things. Working with him is a pleasure. I felt pressure to rise to the occasion since I had only been in a few group shows and I only shared three drawings in this new modality. I didn't have as much depth in my catalog to show what the exhibition could be like and I was still learning what I could do technically, in drawing and sculpture. That's an immense level of trust that I’ll always be grateful for. I wasn't able to be present at the install and his team did a wonderful job. The experience made me less cynical about the art world.

If you have the opportunity to work with a space that trusts you, communicates well, and has a great attitude, it changes everything. I still feel like I’m improving and to be given so much trust at the beginning made me realize I need to respect myself more, because if someone respects and believes in me so much all while I’m engaging in incredibly negative self-talk, it just conflicts with the reality of what is actually happening. The world isn't seeing me as harshly as I'm seeing myself. I had graduated from undergrad and a year had passed, I didn't have any significant prospects on the horizon.. I kind of have to accept how much I did for myself and it is making me appreciate my own work ethic a bit more. I tend to downplay the amount of effort I put into things but these recent experiences made me more confident to feel outwardly like yeah, I did that and I’m proud of it. If this works for somebody, take this advice, work on yourself first and be sure you're solvent in who you are before you’re put in a position to be seen by other people. I wish I had done more of that work earlier so as to prevent personal conflicts that could have been avoided had I had a healthier frame of mind.

JS: It’s kind of a unique situation. So, my grandmother passed away in the fall of 2021 and I was working on an etching with Pigeonhole Press. The etching was a cross with eyes superimposed in front of it, that led me down the rabbit hole of wanting to make more cross imagery. When I was visiting her before she passed, I saw a cross in a museum in Bardejov that really spoke to me. It was a medieval type of hand-held cross that would be used in religious ceremonies. It inspired the first drawing I made using this additive and reductive process. I made four of them and posted three online, and after I posted the third one I found Turley Gallery. We had a visit over Zoom and it just went from there. Ryan Turley has facilitated a fantastic community in Hudson. He's an artist as well and his care for other artists really comes through in how he does things. Working with him is a pleasure. I felt pressure to rise to the occasion since I had only been in a few group shows and I only shared three drawings in this new modality. I didn't have as much depth in my catalog to show what the exhibition could be like and I was still learning what I could do technically, in drawing and sculpture. That's an immense level of trust that I’ll always be grateful for. I wasn't able to be present at the install and his team did a wonderful job. The experience made me less cynical about the art world.

If you have the opportunity to work with a space that trusts you, communicates well, and has a great attitude, it changes everything. I still feel like I’m improving and to be given so much trust at the beginning made me realize I need to respect myself more, because if someone respects and believes in me so much all while I’m engaging in incredibly negative self-talk, it just conflicts with the reality of what is actually happening. The world isn't seeing me as harshly as I'm seeing myself. I had graduated from undergrad and a year had passed, I didn't have any significant prospects on the horizon.. I kind of have to accept how much I did for myself and it is making me appreciate my own work ethic a bit more. I tend to downplay the amount of effort I put into things but these recent experiences made me more confident to feel outwardly like yeah, I did that and I’m proud of it. If this works for somebody, take this advice, work on yourself first and be sure you're solvent in who you are before you’re put in a position to be seen by other people. I wish I had done more of that work earlier so as to prevent personal conflicts that could have been avoided had I had a healthier frame of mind.

GT: What kind of atmosphere do you prefer to work in where you feel most productive and motivated? You mentioned that in the past what worked for you was total isolation and distance from social media. Where are you now in terms of that?

JS: I don’t isolate anymore in the same way, I do take time for myself though. What I did before was unnecessary and made my mental health worse at the time. But I did need that crucible of pressure. I still prefer to evaluate my own ideas before calling on anyone for advice, and anyone I do call on is a trusted peer. Now, when working I go between music and silence. It just depends on what I’m feeling because the day I have will influence what I make. If one day I don’t feel capable of tackling one aspect of a drawing, I’ll work on another. So, trying to accommodate my needs is important. Sometimes I need to just be completely quiet.

JS: I don’t isolate anymore in the same way, I do take time for myself though. What I did before was unnecessary and made my mental health worse at the time. But I did need that crucible of pressure. I still prefer to evaluate my own ideas before calling on anyone for advice, and anyone I do call on is a trusted peer. Now, when working I go between music and silence. It just depends on what I’m feeling because the day I have will influence what I make. If one day I don’t feel capable of tackling one aspect of a drawing, I’ll work on another. So, trying to accommodate my needs is important. Sometimes I need to just be completely quiet.

GT: We have talked about some of the present themes in your work such as sexuality, heritage, and memory. When you are planning what the composition will look like, how does that process start out for you? Can you give us a more in depth explanation of your process?

JS: I usually start with writing a series of words, characteristics and feelings that I want to elicit, on the spot without overthinking. I try to unpack why those are coming up, essentially doing a personal inventory on my current emotions. Visually, I start with the inked, ornate framing on paper. I sketch it out on graph paper, then I’ll begin toning a piece of drawing paper. While that’s drying I take a photo of the drawing on graph paper and I’ll put it into GIMP, a free digital editing program, and then there are all these minimal editing moves like, beauty is in the millimeters type of tweaks that I make to the design before drawing and inking as the first step of the drawing. Then I’ll take a picture of that and cycle through a series of images I have taken or sourced and find what naturally fits the composition. Nothing is ever exactly replicated as it is mocked up. I always try to capture the spirit of the image because the emotion behind it is what I resonate with. The improvisation between the prepared paper and the overlayed images makes me feel more comfortable with the amount of hours of work I put in. There is an element of spontaneity even if it is not immediately noticeable. It’s all an attempt to filter without losing anything and it’s an act of refinement. It forces me to take a step back and have a bit of a barrier with it so I don’t become too personally engrossed or invested in a way that might hurt the work.

JS: I usually start with writing a series of words, characteristics and feelings that I want to elicit, on the spot without overthinking. I try to unpack why those are coming up, essentially doing a personal inventory on my current emotions. Visually, I start with the inked, ornate framing on paper. I sketch it out on graph paper, then I’ll begin toning a piece of drawing paper. While that’s drying I take a photo of the drawing on graph paper and I’ll put it into GIMP, a free digital editing program, and then there are all these minimal editing moves like, beauty is in the millimeters type of tweaks that I make to the design before drawing and inking as the first step of the drawing. Then I’ll take a picture of that and cycle through a series of images I have taken or sourced and find what naturally fits the composition. Nothing is ever exactly replicated as it is mocked up. I always try to capture the spirit of the image because the emotion behind it is what I resonate with. The improvisation between the prepared paper and the overlayed images makes me feel more comfortable with the amount of hours of work I put in. There is an element of spontaneity even if it is not immediately noticeable. It’s all an attempt to filter without losing anything and it’s an act of refinement. It forces me to take a step back and have a bit of a barrier with it so I don’t become too personally engrossed or invested in a way that might hurt the work.

GT: You seem to have a reliable process that really works for you but at times do you ever feel stuck and if so, how do you get yourself unstuck or maneuver through that?

JS: I have to think on that one. Well, the way my practice is structured now with the stop gaps I give myself, it helps me realize moments that could make me stuck earlier on. If I notice I am making a drawing I’m not into, in the sketching process, I'll stop and start a new one. If I've toned the paper and I don’t like the look of it or the ink isn’t responding well I just need to use a different kind of paper or work with that texture to the end depending on my temperament. The process helps me see down the line and that prevents me from being stuck the way I used to be. Sometimes I do feel lost but then there’s the benefit of having all these pictures I’ve taken for years, here and in Slovakia. I use them as access points to the written words to see what reflects how I feel and I follow that where it takes me. I think the way to relieve yourself of being stuck is to confront what got you there and consider why what you're doing feels inhibiting to get an answer.

GT: That is such an insightful take on this, thank you! So, lastly, what is next for you or what are you excited about moving forward? What is the next goal or step in mind for you?

JS: I am excited that I am being myself this fully for the first time in my life. I sometimes have a hard time knowing who I am because I thought it had to be built under the guise of other cultural structures, or that I had to accept other people’s perspectives of me as a fact. I am better at all the things I never thought I could be good at; Drawing, my friendships, family relationships, romantic relationships. Because making art has become such an inherent aspect of how I live, it led me to realize what I need to improve personally which maybe isn’t typical but it’s getting me where I need to go.

GT: This has been so wonderful, thank you so much Jan!

JS: Yeah, thanks a lot!

JS: I have to think on that one. Well, the way my practice is structured now with the stop gaps I give myself, it helps me realize moments that could make me stuck earlier on. If I notice I am making a drawing I’m not into, in the sketching process, I'll stop and start a new one. If I've toned the paper and I don’t like the look of it or the ink isn’t responding well I just need to use a different kind of paper or work with that texture to the end depending on my temperament. The process helps me see down the line and that prevents me from being stuck the way I used to be. Sometimes I do feel lost but then there’s the benefit of having all these pictures I’ve taken for years, here and in Slovakia. I use them as access points to the written words to see what reflects how I feel and I follow that where it takes me. I think the way to relieve yourself of being stuck is to confront what got you there and consider why what you're doing feels inhibiting to get an answer.

GT: That is such an insightful take on this, thank you! So, lastly, what is next for you or what are you excited about moving forward? What is the next goal or step in mind for you?

JS: I am excited that I am being myself this fully for the first time in my life. I sometimes have a hard time knowing who I am because I thought it had to be built under the guise of other cultural structures, or that I had to accept other people’s perspectives of me as a fact. I am better at all the things I never thought I could be good at; Drawing, my friendships, family relationships, romantic relationships. Because making art has become such an inherent aspect of how I live, it led me to realize what I need to improve personally which maybe isn’t typical but it’s getting me where I need to go.

GT: This has been so wonderful, thank you so much Jan!

JS: Yeah, thanks a lot!

Jan’s website: https://www.jansimonds.com/.