INTERVIEW WITH MADISON BURGER

By Giselle Torres 19/11/2023

Giselle Torres: Madison, you and I met in high school when we both were in the AP photography program at the Chicago Arts Program, Gallery 37. Now, your practice ranges from textile arts to fashion design, printmaking, and photography seems to still lend a hand in that mix. Can you walk me through your journey leading up to where you are now in terms of your craft?

Madison Burger: Yeah, my dad when I was growing up turned my closet-space into a dark room so my first experience with photography was very much through my dad. Once I started college I majored in photography and my love for photography was always there and will always be a part of my practice. As I was doing more analogue work I was more interested in the actual process of making photographs and being more hands on. So, kind of naturally I started in photography but then I realized very quickly that I was more interested in chemistry, textile processes, and my Mom’s background is in fashion and costume design so that was in my subconscious the whole time as well. There was this sort of satisfaction that came with making something that is physical, that you are able to interact with that I was just drawn to a lot more than creating images and those existing as physical prints.

I did a lot of photography for the first couple years of college but I would say about sophomore year going into the end of school when I was thinking about my thesis, I shifted a lot more into fashion design and textile design. When I was at Pratt, I was actually able to create what’s called a ‘customized minor’ so it was something the school has just started offering through their school of interdisciplinary study. The whole objective of that program is to allow students who are in a very specific track the opportunity to explore it further. For me I was majoring in photography and minoring in fashion design and minoring in my customized minor. It was called ‘Speculative Surfaces’ and it was pretty much about creating more environmentally-friendly textiles. So, what I always say in photography is that it was always kind of this language for me to start and figure out what I wanted my voice to be and what I wanted to say in my work. Then I moved towards figuring out ways to still use photography as a mechanical sort-of process but thinking about it in terms of fashion and textiles.

Madison Burger: Yeah, my dad when I was growing up turned my closet-space into a dark room so my first experience with photography was very much through my dad. Once I started college I majored in photography and my love for photography was always there and will always be a part of my practice. As I was doing more analogue work I was more interested in the actual process of making photographs and being more hands on. So, kind of naturally I started in photography but then I realized very quickly that I was more interested in chemistry, textile processes, and my Mom’s background is in fashion and costume design so that was in my subconscious the whole time as well. There was this sort of satisfaction that came with making something that is physical, that you are able to interact with that I was just drawn to a lot more than creating images and those existing as physical prints.

I did a lot of photography for the first couple years of college but I would say about sophomore year going into the end of school when I was thinking about my thesis, I shifted a lot more into fashion design and textile design. When I was at Pratt, I was actually able to create what’s called a ‘customized minor’ so it was something the school has just started offering through their school of interdisciplinary study. The whole objective of that program is to allow students who are in a very specific track the opportunity to explore it further. For me I was majoring in photography and minoring in fashion design and minoring in my customized minor. It was called ‘Speculative Surfaces’ and it was pretty much about creating more environmentally-friendly textiles. So, what I always say in photography is that it was always kind of this language for me to start and figure out what I wanted my voice to be and what I wanted to say in my work. Then I moved towards figuring out ways to still use photography as a mechanical sort-of process but thinking about it in terms of fashion and textiles.

GT: You mentioned “Speculative Surfaces” and I was not aware that this project was something you began developing in college, I had the understanding it came to fruition once you had graduated. What are some lessons you have learned from being in an entrepreneurial role as the Founder and CEO of Speculative Surfaces and balancing this with your artistic practice and still making time for other activities in everyday life?

MB: So the name “Speculative Surfaces” is what I named my customized minor and when I was in school I was starting to experiment with thinking about bio-materials and these sort-of next generation materials that could be used in fashion design or furniture design. I graduated during the pandemic, so I had a lot of time to just experiment at home.

That’s where I actually started doing a lot of research around this leather alternative material; Bacterial cellulose is the scientific name for it. I started to get the ideas for it when I was in school but didn’t start physically creating prototypes and doing the research till after I graduated.

MB: So the name “Speculative Surfaces” is what I named my customized minor and when I was in school I was starting to experiment with thinking about bio-materials and these sort-of next generation materials that could be used in fashion design or furniture design. I graduated during the pandemic, so I had a lot of time to just experiment at home.

That’s where I actually started doing a lot of research around this leather alternative material; Bacterial cellulose is the scientific name for it. I started to get the ideas for it when I was in school but didn’t start physically creating prototypes and doing the research till after I graduated.

Then in 2021, I had been researching this material, playing around a lot for about a year and that is when I decided to found my LLC which is called Speculative Surfaces. And thinking about how I can continue this research and move it into a space where I can actually have all the resources to continue to perfect this material and then eventually get it to a point where I can grow it at a scale so that it can actually be used out in the environment. So right now, my full-time-ish role is actually in art consulting so I’m working on a bunch of random projects and we work with clients who are interested in purchasing artwork for their own personal spaces or commercial spaces so that’s kind of my day job.

The research I have been doing with Speculative Surfaces has evolved to be very much aligned with another non-profit here in Chicago that’s called Chi-Town Bio. They’re hoping to open up next year the first biology makerspace in Chicago. So, once everyone graduates or if they’re not in school but still want access to a space where they can pursue research around biology and environmental sciences, that’s kind of their goal. I’ve got my sort of research and our goal is to move my research into their lab space and then have the resources there as well to continue research and development and get it to a point where it’s a material that can be used out in the world.

GT: Okay, wonderful. I can't wait to see how this project progresses with the time and attention you are giving it! You mentioned ChiTownBio and the sense of community you have benefited from there. Are there other ways in which you have found a sense of community in the realm of biological creativity?

MB: Yeah, totally! So, the founder of ChiTownBio, Andy Scarpelli who is also a professor at The School of the Art Institute and he teaches a lot of classes that are based around this mix of arts, design, science, community activism, and community involvement. ChiTownBio, working with this organization has been a huge community driven project. The whole purpose of ChiTownBio is to really offer a space for people in the community of Chicago to have access to a lab where they can experience their own sort-of research. Working with them and also working with this organization called Biodesign Challenge who every year have a call for applications for people to pitch some sort-of community involved environmental project. Last year, I was actually on the ChiTownBio team for this Biodesign Challenge - it was called the ‘Sprint Challenge’.

It was sponsored by Mars Wrigley who is a Chicago-based company. In this group there were people of all different backgrounds in science, mathematics, urban planning, all kinds of things and we pitched this project. It was called “Sprouted” and we talked about all of the vacant land that exists throughout Chicago, predominantly on the South-West side but also the historical ties to this land being heavily polluted, disproportionate amounts of pollution in communities on the Southwest side of Chicago as opposed to the North side of Chicago. We were really looking at this sort-of as why these neighborhoods have not experienced the same kind of environmental care as other parts of Chicago.

What we developed with our project was how we could turn these plots of land into micro-forests in the city to not only use native plants to remove all of the toxins that are in the soil but allow these spaces to reinvent themselves into community driven gardens that would grow different crops that are native to the midwest. So, that was a huge community-engaged project and we went into some of these neighborhoods and talked to the people who lived there and asked them “What’s missing from your community in terms of the environment?” and a lot of these people talked about how they are in food deserts, how there is really poor access to healthy food and options that are affordable. This was a very community-driven project that was a product of working directly with ChiTownBio.

In terms of the interdisciplinary nature of my work right now, it is very much in this space of thinking about this textile I am developing and how it has a greater impact in the world today in terms of removing the traditional process of leather-tanning which creates heavy pollution and all kinds of environmental problems. I would say my community-oriented work exists in thinking about environmental sustainability and how a place like a community garden can create a new environment for some of these neighborhoods.

MB: Yeah, totally! So, the founder of ChiTownBio, Andy Scarpelli who is also a professor at The School of the Art Institute and he teaches a lot of classes that are based around this mix of arts, design, science, community activism, and community involvement. ChiTownBio, working with this organization has been a huge community driven project. The whole purpose of ChiTownBio is to really offer a space for people in the community of Chicago to have access to a lab where they can experience their own sort-of research. Working with them and also working with this organization called Biodesign Challenge who every year have a call for applications for people to pitch some sort-of community involved environmental project. Last year, I was actually on the ChiTownBio team for this Biodesign Challenge - it was called the ‘Sprint Challenge’.

It was sponsored by Mars Wrigley who is a Chicago-based company. In this group there were people of all different backgrounds in science, mathematics, urban planning, all kinds of things and we pitched this project. It was called “Sprouted” and we talked about all of the vacant land that exists throughout Chicago, predominantly on the South-West side but also the historical ties to this land being heavily polluted, disproportionate amounts of pollution in communities on the Southwest side of Chicago as opposed to the North side of Chicago. We were really looking at this sort-of as why these neighborhoods have not experienced the same kind of environmental care as other parts of Chicago.

What we developed with our project was how we could turn these plots of land into micro-forests in the city to not only use native plants to remove all of the toxins that are in the soil but allow these spaces to reinvent themselves into community driven gardens that would grow different crops that are native to the midwest. So, that was a huge community-engaged project and we went into some of these neighborhoods and talked to the people who lived there and asked them “What’s missing from your community in terms of the environment?” and a lot of these people talked about how they are in food deserts, how there is really poor access to healthy food and options that are affordable. This was a very community-driven project that was a product of working directly with ChiTownBio.

In terms of the interdisciplinary nature of my work right now, it is very much in this space of thinking about this textile I am developing and how it has a greater impact in the world today in terms of removing the traditional process of leather-tanning which creates heavy pollution and all kinds of environmental problems. I would say my community-oriented work exists in thinking about environmental sustainability and how a place like a community garden can create a new environment for some of these neighborhoods.

GT: That sounds so purifying and replenishing. I’m curious as to what the community’s response was to your group doing this project. Do they understand the background of the goal you all had in mind?

MB: There was definitely a learning curve in explaining why some of these plots of land for example, you can’t just go in and plant corn and then eat the corn because it is going to be contaminated. I would say there was a learning curve around why chemicals like lead and iron exist in the soil. Once we talked about that, they were definitely very receptive to this idea that we can plant native crops, crops that will live year round in Chicago’s environment, to do the work in terms of purifying the soil and regenerating it.

MB: There was definitely a learning curve in explaining why some of these plots of land for example, you can’t just go in and plant corn and then eat the corn because it is going to be contaminated. I would say there was a learning curve around why chemicals like lead and iron exist in the soil. Once we talked about that, they were definitely very receptive to this idea that we can plant native crops, crops that will live year round in Chicago’s environment, to do the work in terms of purifying the soil and regenerating it.

And as a couple of years have gone by, these plants can all be removed and then that plot of land can be given back to the community to use for harvesting food with crops that people would want to eat. Overall the different people that we talked to were pretty receptive to this idea of taking this contaminated and really sad plot of land that’s not being used at all and do something meaningful with it that also gives back to the area that is already suffering from a lack of resources and food.

GT: Yeah, and what you all were doing was not invasive and you were using land that was not in use anyway and you are bringing about a solution to a big problem that has been facing Chicagoland and many other places for a very long time. I think that’s amazing!

MB: So, yeah our next step that we really want to see happen you know, we pitched this and our team actually ended up winning the Biodesign Challenge so that was really wonderful. Our next steps are that we would really love to see this project happen. We did a case study which was a test site to just show what’s possible. We very much through ChiTownBio want to take this project and bring it to city officials and hopefully create a partnership with Mars Wrigley to be able to fund these kinds of projects. The goal would be to see the city start putting money back into these communities and environments because it’s not like we’re pitching to build a whole new facility or something like that that is super costly. It is more about coming up with minimal funding to allow these plots of land to start to be turned over.

GT: Yeah, and what you all were doing was not invasive and you were using land that was not in use anyway and you are bringing about a solution to a big problem that has been facing Chicagoland and many other places for a very long time. I think that’s amazing!

MB: So, yeah our next step that we really want to see happen you know, we pitched this and our team actually ended up winning the Biodesign Challenge so that was really wonderful. Our next steps are that we would really love to see this project happen. We did a case study which was a test site to just show what’s possible. We very much through ChiTownBio want to take this project and bring it to city officials and hopefully create a partnership with Mars Wrigley to be able to fund these kinds of projects. The goal would be to see the city start putting money back into these communities and environments because it’s not like we’re pitching to build a whole new facility or something like that that is super costly. It is more about coming up with minimal funding to allow these plots of land to start to be turned over.

GT: There are so many vacant plots and land not being used that can totally be used for this and would not be exponentially costly by any great means. You have discussed the bacterial yeast strands known as bacterial cellulose and how it is a sustainable leather-like alternative. I would love to learn about how you discovered this technique. Is there any one person that you discovered one day and were like “oh my gosh, this is what I want to do!” or that just inspired the direction your work went in terms of finding this method? Also, it would be great to hear about what this process is like in terms of labor, materials, and time?

MB: After I graduated, I was researching a lot of different designers that were using leather grown from mushrooms or starting to use these alternative or environmentally-friendly materials. I came across this woman, Susan Lee who is a huge powerhouse in the world of next generation materials. I came across, I think it was her thesis collection that she put together when she was at Central Saint Martins in London. Her collection was a bunch of these beautiful garments that she made that were made out of this scoby bacterial cellulose material. Scoby stands for Symbiotic Culture of Bacteria in Yeast.

MB: After I graduated, I was researching a lot of different designers that were using leather grown from mushrooms or starting to use these alternative or environmentally-friendly materials. I came across this woman, Susan Lee who is a huge powerhouse in the world of next generation materials. I came across, I think it was her thesis collection that she put together when she was at Central Saint Martins in London. Her collection was a bunch of these beautiful garments that she made that were made out of this scoby bacterial cellulose material. Scoby stands for Symbiotic Culture of Bacteria in Yeast.

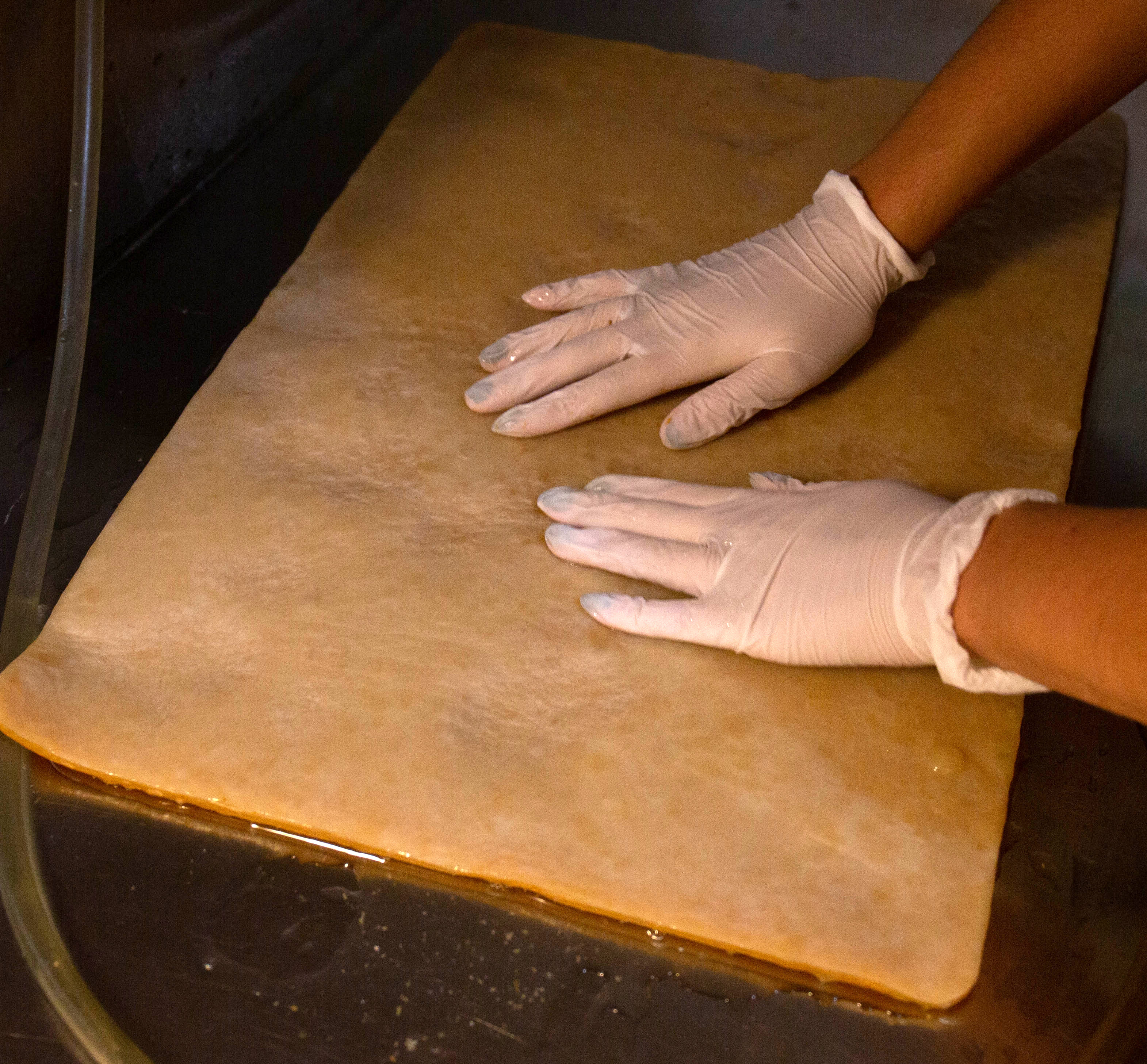

Where the research really started was growing my own kombucha at home and fermenting it because the biofilm that grows on top of the kombucha is called a scoby and it’s also referred to as a “mother” for the kombucha. That film that is on top of the liquid is what helps keep the kombucha in a fertile environment and helps retain all the bacterial developments that are happening. So, I saw this collection and was super inspired and started growing my own kombucha at home in the darkroom because there was a sink in there. My dad let me move a lot of the photo equipment out and turn it into my own little lab space at my parent’s place. It was no longer a darkroom and was now a lab space for all my experiments. That’s where the research started and then after I grew the first piece and dried it out, cleaned it up, well, I’ll show you. So these are some samples of the leather and a pair of shoes that I made.

GT: These are amazing. If I’m correct, you have made a multitude of shoes, right?

MB: So yeah, when I was at Pratt, you had to choose an emphasis for your fashion design and I chose shoe design. Leather is probably the most common material used in shoe design for durability. I made a bunch of shoes using upcycled leather and leather scraps and once I had more of this scoby prototype I started to make more test samples.

GT: I am noticing on this pair, it states on the sole, “these shoes took two months to grow”.

![Shoes made from leather alternative on display at a pop-up exhibition at Venteux Chicago, 2022]()

MB: So yeah, when I was at Pratt, you had to choose an emphasis for your fashion design and I chose shoe design. Leather is probably the most common material used in shoe design for durability. I made a bunch of shoes using upcycled leather and leather scraps and once I had more of this scoby prototype I started to make more test samples.

GT: I am noticing on this pair, it states on the sole, “these shoes took two months to grow”.

MB: I like this little label because I wanted to bring it back to the process of how these came to be. Some of these details [on this shoe] are using conventional leather just to show that you can't really tell the difference between the two materials. Here are some samples. After I grew this first piece and dried it out, it turns black naturally as it oxidizes. So, it is not dyed, this is the natural color. I just completely fell in love with the material because it’s got this natural grain that exists because it is yeast and bacteria. These single-celled organisms are creating this unique pattern. I really resonated with how this material is already so effortlessly similar to leather in terms of having this natural grain. That really spoke to me and so from that first piece I continued to experiment with growing different thicknesses. [Madison then hands me another sample piece that is akin to parchment paper in thickness and is a bright fuschia color.]

For example, this is the same material and it only took a week to grow. The longer it grows, the thicker the material becomes. So, the first sample took three months to grow and this one in comparison gives you an example of what something a week old can look like. Also, just seeing all the material possibilities and routes of this material is all very exciting.

For example, this is the same material and it only took a week to grow. The longer it grows, the thicker the material becomes. So, the first sample took three months to grow and this one in comparison gives you an example of what something a week old can look like. Also, just seeing all the material possibilities and routes of this material is all very exciting.

GT: Using a material like this harbors so much room for creative possibilities because you are working with a material that has differing characteristics that it takes on depending on the treatment you give it. It seems as though you have so much more room for possibilities compared to if you were just using typical leather where specific desired characteristics are already established in the leather market doesn’t tend to stray from.

MB: Yeah, completely, feel free to look through these. Another thing that got my gears turning was that the material also grows to the environment that it is in. If I, for example, created these 3-D printed containers and the shapes of the containers are pattern pieces of what a shoe would look like. A huge part of the fashion industry that is a big problem is material waste. You can think about how you can cut ten patterns out of a piece of leather and there is so much that from the pieces of material that don’t line up that it becomes a big problem. What’s cool about this material is say I collaborate with a shoe designer who knows exactly what all their patterns are going to be like and you can create molds that you can grow all the material in so it is growing it to size in the pattern that it would be cut down to as a way to eliminate all that waste. [Madison then hands me a rectangular leather sample that is an amber tone.]

This for example was grown in a rectangular container. And this one, it’s kind-of ripped but you can see it was growing in a circular container. So, it’s not cut at all, that’s completely natural.

MB: Yeah, completely, feel free to look through these. Another thing that got my gears turning was that the material also grows to the environment that it is in. If I, for example, created these 3-D printed containers and the shapes of the containers are pattern pieces of what a shoe would look like. A huge part of the fashion industry that is a big problem is material waste. You can think about how you can cut ten patterns out of a piece of leather and there is so much that from the pieces of material that don’t line up that it becomes a big problem. What’s cool about this material is say I collaborate with a shoe designer who knows exactly what all their patterns are going to be like and you can create molds that you can grow all the material in so it is growing it to size in the pattern that it would be cut down to as a way to eliminate all that waste. [Madison then hands me a rectangular leather sample that is an amber tone.]

This for example was grown in a rectangular container. And this one, it’s kind-of ripped but you can see it was growing in a circular container. So, it’s not cut at all, that’s completely natural.

GT: We live in a world where we are prominent consumers and people for example will say “Wow, I really want a pair of shoes by Madison Burger” and once they decide that the first ones they bought are not suiting their style anymore they may want a new pair of your shoes down the line. The rate at which we consume that provokes a demand for companies to produce so much that ends up in landfills. Do these materials break down with time? Are they biodegradable?

MB: Yeah, so, right now the biggest challenge with the RND (research and development) is that this material, without it being sealed, for example these are all sealed with natural waxes but long-term this material will start to break down if it is exposed to water or humid environments. On its own and not treated at all it’s a hundred percent biodegradable. My goal is to create some kind of topical treatment that is not derived from plastics or any kinds of oil and instead can be something that protects the material but that also can also break down over time.

MB: Yeah, so, right now the biggest challenge with the RND (research and development) is that this material, without it being sealed, for example these are all sealed with natural waxes but long-term this material will start to break down if it is exposed to water or humid environments. On its own and not treated at all it’s a hundred percent biodegradable. My goal is to create some kind of topical treatment that is not derived from plastics or any kinds of oil and instead can be something that protects the material but that also can also break down over time.

So, for these shoes for example, minus some of these parts [that are real leather that added to the heel strap so demonstrate the similarities in material characteristics], someone could just put these in the compost and they could break down in a couple of months. I would say, one of the biggest challenges for these new next generation materials is coming up with a durability and water-proofing solution. Something else that is a really big concern is that there are still a lot of companies who are creating better materials for the environment but they’re still using plastic. I would say there is definitely a lot of brainwashing that happens around sustainability in the fashion environment. It's on us as consumers as well to do that research and to think about how this material is actually made. Is buying a vintage leather jacket still better than buying a new jacket that is made out of recycled materials but yet it still has a lot of plastic in it? You then have to think about how every time you wash that pair of pants that is made of plastics the microplastics are a huge problem.

I like what you said about consumerism. After moving into textiles and fashion, that really deterred me from the traditional route because as much as I like making and designing and bringing things into the world, I became hyper-aware that I don’t want to be putting more waste out into the environment if it’s not something that can have a symbiotic relationship with the environment. Shoe-making, fell in love with that process but not with the fact that all the things I was making were coming from animal-leather. I was thinking, ‘Okay, fashion is always going to exist and there is always going to be this level of people wanting to consume and buy more things and feel good about what they’re wearing. So, how can we faze out what those inputs are in terms of materials? How to have this fashion that everybody loves but have it be better for the environment long-term?’

I like what you said about consumerism. After moving into textiles and fashion, that really deterred me from the traditional route because as much as I like making and designing and bringing things into the world, I became hyper-aware that I don’t want to be putting more waste out into the environment if it’s not something that can have a symbiotic relationship with the environment. Shoe-making, fell in love with that process but not with the fact that all the things I was making were coming from animal-leather. I was thinking, ‘Okay, fashion is always going to exist and there is always going to be this level of people wanting to consume and buy more things and feel good about what they’re wearing. So, how can we faze out what those inputs are in terms of materials? How to have this fashion that everybody loves but have it be better for the environment long-term?’

GT: I agree and like many others I have been subject to the brainwashing that companies weave into their ads and such. I know for me, personally the problem of sustainability feels so great and that me being one person, I struggle to feel like I am doing enough sometimes. What advice do you have for those who want to do more? What are some ways we can be more sustainable that we maybe aren’t aware of?

MB: I try to avoid buying anything that’s new. So, I will say that being able to shop at second-hand shops and vintage stores, you know, places that have a surplus of clothes that are still in excellent condition but maybe not a part of the new trends that are going on, I think that’s a great place to start in terms of buying things, try not to buy new. I also think that mending, making use of the clothes you already have and not throwing away a sweater when it gets a huge rip in it. I think the idea that things are just so disposable is another part of the problem. The fact that if you do have a sweater that has a hole in it and you think about the time it takes to mend that sweater, as opposed to buying a new sweater that’s cheap and the easy gratification that comes with that. I would say, shop second-hand, make use of the clothes that you do have, and just be more aware.

MB: I try to avoid buying anything that’s new. So, I will say that being able to shop at second-hand shops and vintage stores, you know, places that have a surplus of clothes that are still in excellent condition but maybe not a part of the new trends that are going on, I think that’s a great place to start in terms of buying things, try not to buy new. I also think that mending, making use of the clothes you already have and not throwing away a sweater when it gets a huge rip in it. I think the idea that things are just so disposable is another part of the problem. The fact that if you do have a sweater that has a hole in it and you think about the time it takes to mend that sweater, as opposed to buying a new sweater that’s cheap and the easy gratification that comes with that. I would say, shop second-hand, make use of the clothes that you do have, and just be more aware.

Going into a fashion program and also having a background in design just creates a very different relationship that I have naturally to clothes and consuming materials. There is a huge learning curve for people who don’t go that creative route. It's a tough situation because there’s a lot of designers who are making incredible pieces that are all about creative expression and having the right to do that. We’ve kind-of created this huge network of designers that it’s now tricky because as a designer, say you have this brand that has existed for like 50 years and there’s this legacy behind that. You don’t want to erase that and just get rid of it. I think it’s also about how if we want to continue making clothes and bringing new things into the world, just being more intentional is necessary.

GT: It is so necessary and an act of resistance. In the face of huge brands that have their legacies behind them mixed with the societal pressure we feel to demonstrate our significance and self-expression through what we wear, there is going to be that tug of resistance. I find it so wonderful that through your designs, people can participate in fashion and simultaneously feel like they have the power to make a better, more sustainable choice that lifts that inner-strain on them.

MB: Yeah, totally. It’s also about everyone in general making more of an effort to be aware and understand that you may think you’re doing your job with other elements of your life and fashion is not really something that is a factor or that it doesn’t have as big of an impact as other things do. It’s also just thinking about these systems that exist and on a large scale and what kind of detriment they're actually doing. There’s a documentary that’s called Slay that is incredible. It’s an expose around the fur and leather trade. It really unpacks a lot of false information that the media spreads and shares to make us believe that my wool sweater is a better purchase than a plastic raincoat. When you look at, for example, the amount of energy, water, and inputs that are required to create wool and charmere and things like that, you actually learn it’s not better for the environment. It is really energy and water intensive so we can also think about water-scarcity which is a huge problem and we’re going to get to a point where we can’t just use water as a resource so freely because it’s finite.

GT: It is so necessary and an act of resistance. In the face of huge brands that have their legacies behind them mixed with the societal pressure we feel to demonstrate our significance and self-expression through what we wear, there is going to be that tug of resistance. I find it so wonderful that through your designs, people can participate in fashion and simultaneously feel like they have the power to make a better, more sustainable choice that lifts that inner-strain on them.

MB: Yeah, totally. It’s also about everyone in general making more of an effort to be aware and understand that you may think you’re doing your job with other elements of your life and fashion is not really something that is a factor or that it doesn’t have as big of an impact as other things do. It’s also just thinking about these systems that exist and on a large scale and what kind of detriment they're actually doing. There’s a documentary that’s called Slay that is incredible. It’s an expose around the fur and leather trade. It really unpacks a lot of false information that the media spreads and shares to make us believe that my wool sweater is a better purchase than a plastic raincoat. When you look at, for example, the amount of energy, water, and inputs that are required to create wool and charmere and things like that, you actually learn it’s not better for the environment. It is really energy and water intensive so we can also think about water-scarcity which is a huge problem and we’re going to get to a point where we can’t just use water as a resource so freely because it’s finite.

I’ve been speaking in my friend, Doreen Nicholas' class who is a professor at Pratt who teaches in the humanities department. She teaches a class called ‘Making Faking Nature’ that unpacks our human-animal relationship. So this was a film I had her show her students then we all talked about it in an open-conversation. After watching it for the first time, I was completely blown away by the things that we just don’t know.

GT: Yes, I am seeing so many popular brands now advertising how they are introducing lines of clothes that are made from materials such as cotton and linen lately. I am still cautious because I worry if that is enough.

MB: Yeah, you've got both ends that yeah cotton is better for the environment in terms of breaking down but then you have to think about how much water is used in the process. Then you have the inverse of that where you have polyester that is better for the environment because it uses less resources but then you have to think about how it is going to take thousands of years to break down and when washed it produces microplastics. There is no win-win situation. It’s exciting to see how many companies exist in this space of biomaterials and next generation biological materials.

GT: Yes, I am seeing so many popular brands now advertising how they are introducing lines of clothes that are made from materials such as cotton and linen lately. I am still cautious because I worry if that is enough.

MB: Yeah, you've got both ends that yeah cotton is better for the environment in terms of breaking down but then you have to think about how much water is used in the process. Then you have the inverse of that where you have polyester that is better for the environment because it uses less resources but then you have to think about how it is going to take thousands of years to break down and when washed it produces microplastics. There is no win-win situation. It’s exciting to see how many companies exist in this space of biomaterials and next generation biological materials.

GT: Yes, very exciting and I wonder where we’ll be in the future with all of this and how it evolves. You mentioned that your parents were big inspirations for you in terms of your craft. Typically, craft wisdoms are passed down through generations and or communal connections. You talked about Susan Lee, are there any other figures who have entered your life one way or another that have had a notable impact on you?

MB: In terms of making, I grew up with all the stories and sketches my mom shared with me, she studied fashion design with an emphasis in costume design. She would make a lot of my clothes and Halloween costumes and that was something I was always paying attention to. How you can create this idea and bring it to life. My mom was definitely a big factor in thinking about making and materials. She worked with a company that dealt with selling leather gloves for industrial uses for mechanics and people who use their hands a lot. She would always bring leather samples home that they were inspecting so that was something that I didn’t think much of growing up but looking back it definitely had a place in my life.

In terms of makers, I really gravitate towards people like Sheila Hicks and Ruth Aswa. They both were creating textiles in this craft environment around the same time and bringing these really new approaches to thinking about fabric and materials in a different kind of way. I’d say it was a mix of looking at the things that my mom made and all of her ancestors who worked in fashion-related fields and the history behind this craft of textiles. Also the professors I had in the fashion department who taught making but also had their own fashion lines. There were a lot of different factors for sure.

GT: It takes a village! You talked a little bit about how there are some tweaks you hope to work through in the development of your leather to make it more durable and able to withstand all elements. Is this a fairly new method that has been brought into the fashion industry, this use of bacterial cellulose for making sustainable-leather?

MB: There are many companies around the world that have been developing leather-like alternatives or other material alternatives over the past ten to fifteen years. It very much is a new sort-of field. The only company that I know of that I believe is pretty close to having the material ready for consumer purchase is called Mico works. They are creating mycelium leather. Out of all the companies I think they’re the farthest along. They’ve done collaborations with Stella McCartney and different brands that have started to promote their materials. It is very much a new field.

MB: There are many companies around the world that have been developing leather-like alternatives or other material alternatives over the past ten to fifteen years. It very much is a new sort-of field. The only company that I know of that I believe is pretty close to having the material ready for consumer purchase is called Mico works. They are creating mycelium leather. Out of all the companies I think they’re the farthest along. They’ve done collaborations with Stella McCartney and different brands that have started to promote their materials. It is very much a new field.

What a lot of companies are doing is using vertical farming. Hypothetically all these materials can be grown in trays that can be stacked. I am noticing in this field that people are taking big industrial spaces and converting them into these vertical farms to grow these materials. What has presented itself as a possibility is to have a climate controlled environment that has a stack of a bunch of different trays that can grow the material that can be tracked through sensor technology to see what’s growing and what might get contaminated that then can be harvested.

A lot of companies have been doing research in this field for some time but in a few years I think we’ll see these materials become more commercially available. The research has existed but there are a lot of hurdles in terms of funding to go towards this new competitor material. Some of the most interesting things to be discovered have come from institutions or individual companies getting outside funding for the sake of research. That’s where a lot I think can happen. When we’re able to say we don’t have a specific goal in mind that we have to achieve but we’re going to research all areas of a field. From there is where you uncover things you may not have known or been looking for.

GT: There is so much possibility in the world of sustainability! Where do you see this going in the future? Do you believe people will be receptive to it? It seems as though many brands have been adopting more sustainable mindsets.

MB: Yeah, I would say so. I have kind of pivoted to become a lot more involved with ChiTownBio. I joined as a board member to help with getting a lab space set up. My goals and what I see happening is to be able to pursue all the future research at a facility that would have the tools and resources that I would need to do the right kind of material testing or any other kinds of research that is not accessible when you don’t have a lab.

I had an article published about this work and this material in the Council for Fashion Designers of America. Ever since it was published I have gotten inquiries once every month from some designers from around the world asking for material samples. It’s interesting because you have the demand but not the supply yet. Everytime I receive an email like that it’s very encouraging because it shows that even though this material is not ready to go, when it is there are going to be people and designers who want to use it and utilize it in their collections. I know there is a lot more research to happen and there’s going to be a lot of hurdles to overcome in terms of creating the most durable, environmentally-friendly, and waterproof solution, I am confident that once these materials are readily available there’s going to be this natural shift in the industry to be more conscious and to use better materials.

GT: There is so much possibility in the world of sustainability! Where do you see this going in the future? Do you believe people will be receptive to it? It seems as though many brands have been adopting more sustainable mindsets.

MB: Yeah, I would say so. I have kind of pivoted to become a lot more involved with ChiTownBio. I joined as a board member to help with getting a lab space set up. My goals and what I see happening is to be able to pursue all the future research at a facility that would have the tools and resources that I would need to do the right kind of material testing or any other kinds of research that is not accessible when you don’t have a lab.

I had an article published about this work and this material in the Council for Fashion Designers of America. Ever since it was published I have gotten inquiries once every month from some designers from around the world asking for material samples. It’s interesting because you have the demand but not the supply yet. Everytime I receive an email like that it’s very encouraging because it shows that even though this material is not ready to go, when it is there are going to be people and designers who want to use it and utilize it in their collections. I know there is a lot more research to happen and there’s going to be a lot of hurdles to overcome in terms of creating the most durable, environmentally-friendly, and waterproof solution, I am confident that once these materials are readily available there’s going to be this natural shift in the industry to be more conscious and to use better materials.

GT: You had mentioned that these shoes for example took 3 months to develop and grow. I find that so wonderful because it will encourage us all to slow down in terms of our common desire for consumption as a populace. We would need to be patient for new collections to be released as opposed to the rapid rate that the fashion industry lends itself to. This material in itself is a reminder to slow down and to let the material come to us when it’s ready as opposed to the rate at which consumers want to consume.

MB: Absolutely, when I got to New York, New York Fashion Week was so exciting and brought so much energy. And now I feel so negatively aligned with it at this point because to produce a collection every season is just ridiculous, there’s no reason we need to be consuming like that. That’s also a shift I’m starting to see happen where smaller companies and independent designers aren’t really releasing collections anymore and they are starting to release collections when they come which is refreshing.

There is a lab that has been researching different kinds of mycelium that can break down plastic. They are looking at how these can be put in places to break down petrochemical derived fabrics. It’s exciting to have these new innovations to help clean up this problem. It shouldn't be our solution though because we can keep consuming at the rate we are currently consuming because these little microorganisms will break it down. It's good that they can do that because it will help but we still need to be better as consumers and just slow down.

MB: Absolutely, when I got to New York, New York Fashion Week was so exciting and brought so much energy. And now I feel so negatively aligned with it at this point because to produce a collection every season is just ridiculous, there’s no reason we need to be consuming like that. That’s also a shift I’m starting to see happen where smaller companies and independent designers aren’t really releasing collections anymore and they are starting to release collections when they come which is refreshing.

There is a lab that has been researching different kinds of mycelium that can break down plastic. They are looking at how these can be put in places to break down petrochemical derived fabrics. It’s exciting to have these new innovations to help clean up this problem. It shouldn't be our solution though because we can keep consuming at the rate we are currently consuming because these little microorganisms will break it down. It's good that they can do that because it will help but we still need to be better as consumers and just slow down.

GT: Yeah, and what you said earlier about learning to mend, to sew, to repair is simple and vital wisdom. A lot of the time people learn these skills through information passed down through generations. If they don’t have that luxury and they get a hole in their sweater they immediately think that it can’t serve them any longer so it gets thrown out and replaced. So, that is where resilience and resistance comes into play, that despite this lack of knowing, one can learn and contribute to sustaining the ability of their clothes. Also, in my opinion it just looks really cool [Laughs].

MB: [Laughs] Yeah, totally and it is a good way to customize your own piece and put your own hand-touch in it and to extend the life-span of it.

MB: [Laughs] Yeah, totally and it is a good way to customize your own piece and put your own hand-touch in it and to extend the life-span of it.

GT: Definitely! In terms of ChiTownBio, if someone wanted to get involved in this kind of organization to show their support but are not well-versed in the landscape but wanted to get involved in some way, is that possible?

MB: So even myself, my background is not in chemical engineering or synthetic biology. I’m in these environments sometimes where a lot goes over my head. It’s important to be in environments where you have a lot to learn around the people that you’re with. In terms of ChiTownBio and this work in general, the input from artists, designers, community organizers, and people who work with other nonprofits, are just as valuable as people who are already in the science realm.

Since there is not a material that can be readily available it is still interesting to get feedback in general to see what people think about these new materials and how likely they would be to buy something that is made from a different material that is new. And going back to ChiTownBio, once the space is together, it’s meant to be very much for people who don’t necessarily come from a science background as well. The projects they’re already exploring are incorporating people who have a design background or a community activism background.

MB: So even myself, my background is not in chemical engineering or synthetic biology. I’m in these environments sometimes where a lot goes over my head. It’s important to be in environments where you have a lot to learn around the people that you’re with. In terms of ChiTownBio and this work in general, the input from artists, designers, community organizers, and people who work with other nonprofits, are just as valuable as people who are already in the science realm.

Since there is not a material that can be readily available it is still interesting to get feedback in general to see what people think about these new materials and how likely they would be to buy something that is made from a different material that is new. And going back to ChiTownBio, once the space is together, it’s meant to be very much for people who don’t necessarily come from a science background as well. The projects they’re already exploring are incorporating people who have a design background or a community activism background.

When I was first getting involved with them, I was nervous and kind of felt like an outsider because I was the only person who didn’t have a background or a degree in something that was strictly science or biology. It has also been wonderful to see who else doesn't come from this traditional background because it’s so valuable to have people of different backgrounds come together as opposed to having a room of only scientists who might not have different ideas or perspectives to offer.

GT: That’s so true and that nervousness can be translated to so many different scenarios in life. It is so great that you mentioned that there is room to learn and that our ideas and perspectives all hold value and have a place in the conversation. Lastly, what is next for you that would like to share with us? What are you currently excited about?

MB: A big goal for me is that I really want to make more shoes with the material and I have a space in mind in Chicago that I would love to have a pop-up exhibition that speaks to the process and the research that could kind of be a fashion experience. So, that’s something I am working towards for next year. Another fun update is that this woman, Kat Roberts, she’s getting her degree at Cornell University in New York. We connected a couple years ago because her practice and her thesis was about upcycling and the use of old materials and a political statement toward the fashion industry.

I had a couple pieces of mine in this really beautiful show that just closed at Cornell that was in the fashion department. So, I think Kat and I are going to expand our conversation into more of a mini-documentary that she is creating between myself and I think four other designers that were in that exhibition. I’m looking forward to having a follow-up conversation with Kat because the work that we talk about and the pieces that were in that show were some pieces that I made in school. They were a bunch of these one of a kind handbags that were made from single-use plastic. All the plastic I used I heat-fused into this material and made these handbags from it which were in the show. Now, she wants to expand on the leather alternative and research that has been a product of that thinking. So, I’m excited to have a conversation with her. She wants to take her show that was at Cornell and travel with it.

GT: Wow, you have so much to come! To have this information in a documentary format it will reach a lot more people which is great. If the show comes to Chicago you know I’ll be there haha. This has been so wonderful, thank you Madison!

MB: Yay! Yeah, of course, thank you for chatting with me!

I had a couple pieces of mine in this really beautiful show that just closed at Cornell that was in the fashion department. So, I think Kat and I are going to expand our conversation into more of a mini-documentary that she is creating between myself and I think four other designers that were in that exhibition. I’m looking forward to having a follow-up conversation with Kat because the work that we talk about and the pieces that were in that show were some pieces that I made in school. They were a bunch of these one of a kind handbags that were made from single-use plastic. All the plastic I used I heat-fused into this material and made these handbags from it which were in the show. Now, she wants to expand on the leather alternative and research that has been a product of that thinking. So, I’m excited to have a conversation with her. She wants to take her show that was at Cornell and travel with it.

GT: Wow, you have so much to come! To have this information in a documentary format it will reach a lot more people which is great. If the show comes to Chicago you know I’ll be there haha. This has been so wonderful, thank you Madison!

MB: Yay! Yeah, of course, thank you for chatting with me!

Madison’s website: www.madisonwildsburger.com