By Giselle Torres

29/4/2025

We sat down with Chicago-based multimedia artist Sara Lam to discuss the expansion of her practice from painting to sculpture and mixed media work. We also discussed her surrealist approach to camouflage and mimicry and how her hometown, Texas, continues to inspire her artistic practice.

Giselle Torres: Your most recent works commonly reference camouflage. What does employing camo allow you to discuss or explore in your work?

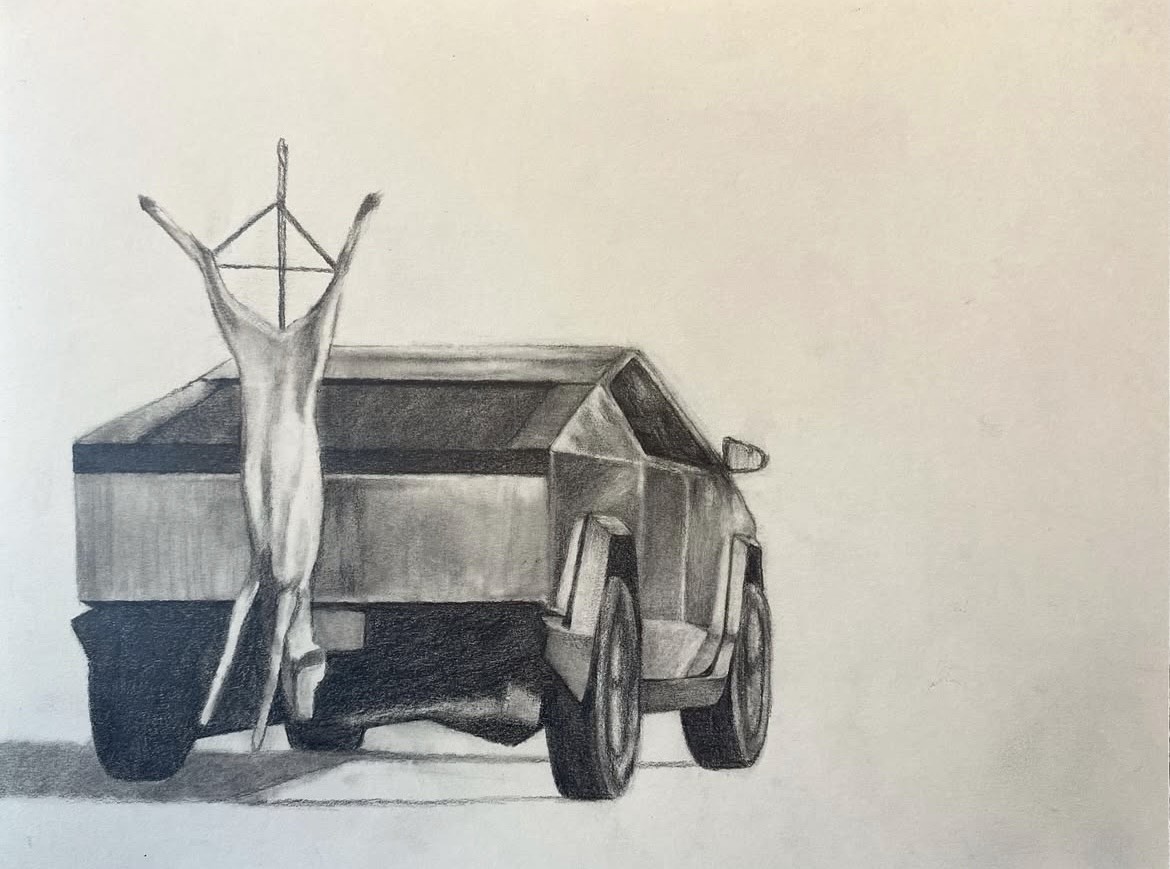

Sara Lam: What draws me to it, in addition to all kinds of multifaceted contextual elements, is the visual textures that it provides. I feel like I’m drawn to materials and textures that kind of do a lot of the legwork for me. I have been thinking a lot about notions of camouflage outside of hunting, but I am only using hunter’s camouflage. I have been thinking a lot about mimicry and adaptations, I guess. Ways I’ve played with mimicry before in my work is by making fake cactuses or fake wood. I feel like camouflage is a means of continuing those themes.

GT: What aspects of mimicry motivate you to keep exploring it as a theme?

SL: I’m tapping into mimicry as a means of portraying or allowing things to take on their own identities.

Sara Lam: What draws me to it, in addition to all kinds of multifaceted contextual elements, is the visual textures that it provides. I feel like I’m drawn to materials and textures that kind of do a lot of the legwork for me. I have been thinking a lot about notions of camouflage outside of hunting, but I am only using hunter’s camouflage. I have been thinking a lot about mimicry and adaptations, I guess. Ways I’ve played with mimicry before in my work is by making fake cactuses or fake wood. I feel like camouflage is a means of continuing those themes.

GT: What aspects of mimicry motivate you to keep exploring it as a theme?

SL: I’m tapping into mimicry as a means of portraying or allowing things to take on their own identities.

GT: That is so fascinating! You recently showed your work at Crit Club, an artist-run critique group. Were there themes or ideas you were excited to explore or get feedback on in your critique?

SL: Yeah! I showed the new pieces I’ve been working on that I recently showed you. And I started the crit with this article that I’ve been reading, “Surrealism, War, and the Art of Camouflage” by Samantha Kavky. It helped me grasp the connections I’ve been making with camouflage, mimicry, and surrealism. It was kind of talking about how humans use camouflage in a different way than animals do. It’s different from the Darwinian ways that animals camouflage. And thinking about that in links to surrealism, which I haven’t studied too much about because I feel like I’ve had a really base-level, Dali-only understanding of it, you know [Laughs].

GT: I love the idea of drawing connections between surrealism and camouflage. You and I have briefly discussed the full-body camo suit you have been working on lately. What has that process been like for you? Have you made garments before?

SL: I've used sewing a little bit in my work, but this is the first time I am making a garment that I intend to wear myself. During Crit Club, people were like maybe don't wear it, but I don't know. It's this spandex material that, from a making standpoint, has been really difficult for me because I'm not a very skilled seamstress, and spandex is just hard to work with. It has these long appendages, and I'm taking a lot of inspiration from Rebecca Horn for that part. She had this piece where she had these long paint brushes attached to her fingers, and she does a lot of body extension kinds of prop performances. So, for my bodysuit, I'd like to have really long fingers on it. I chose spandex because I wanted to make it so that parts of the suit would be bound to the floor, and it would be almost like a trap.

SL: Yeah! I showed the new pieces I’ve been working on that I recently showed you. And I started the crit with this article that I’ve been reading, “Surrealism, War, and the Art of Camouflage” by Samantha Kavky. It helped me grasp the connections I’ve been making with camouflage, mimicry, and surrealism. It was kind of talking about how humans use camouflage in a different way than animals do. It’s different from the Darwinian ways that animals camouflage. And thinking about that in links to surrealism, which I haven’t studied too much about because I feel like I’ve had a really base-level, Dali-only understanding of it, you know [Laughs].

GT: I love the idea of drawing connections between surrealism and camouflage. You and I have briefly discussed the full-body camo suit you have been working on lately. What has that process been like for you? Have you made garments before?

SL: I've used sewing a little bit in my work, but this is the first time I am making a garment that I intend to wear myself. During Crit Club, people were like maybe don't wear it, but I don't know. It's this spandex material that, from a making standpoint, has been really difficult for me because I'm not a very skilled seamstress, and spandex is just hard to work with. It has these long appendages, and I'm taking a lot of inspiration from Rebecca Horn for that part. She had this piece where she had these long paint brushes attached to her fingers, and she does a lot of body extension kinds of prop performances. So, for my bodysuit, I'd like to have really long fingers on it. I chose spandex because I wanted to make it so that parts of the suit would be bound to the floor, and it would be almost like a trap.

GT: So it's going to be quite performative?

SL: Yeah, almost like a gimp suit or a straightjacket or something like that. And I've been thinking about documenting it in a forest area. With that, I am hoping that the end goal is to make the camo wearer look like the one who is trapped or submissive.

GT: How do you feel about physically putting yourself in the work?

SL: I'm making it to my proportions, and I'm not necessarily too excited about putting myself in the work, but I've been thinking about it, and I think it's just the natural course. I feel like I am my work, and all of my work comes from a really personal place. I try to detach myself from it sometimes, but I can't entirely run away from it [Laughs].

SL: Yeah, almost like a gimp suit or a straightjacket or something like that. And I've been thinking about documenting it in a forest area. With that, I am hoping that the end goal is to make the camo wearer look like the one who is trapped or submissive.

GT: How do you feel about physically putting yourself in the work?

SL: I'm making it to my proportions, and I'm not necessarily too excited about putting myself in the work, but I've been thinking about it, and I think it's just the natural course. I feel like I am my work, and all of my work comes from a really personal place. I try to detach myself from it sometimes, but I can't entirely run away from it [Laughs].

GT: You've expressed before that much of your practice is personal and intuitive and how growing up in Texas informs your work. How has living in the Midwest and adulthood influenced how you approach your practice, if any?

SL: This is my fifth or sixth year living in Chicago, and I think the distance has definitely helped give me an outside perspective, or maybe it's just time to be away from my upbringing. It has helped me look at the cultural environments there objectively, I guess. Still, I'm always tying in nostalgic veins through it. So, it's not totally objective. I know that, but I think it has really helped me reinforce crossroads, which I really try to illustrate in my work. I feel like I'm always playing on two different sides of something.

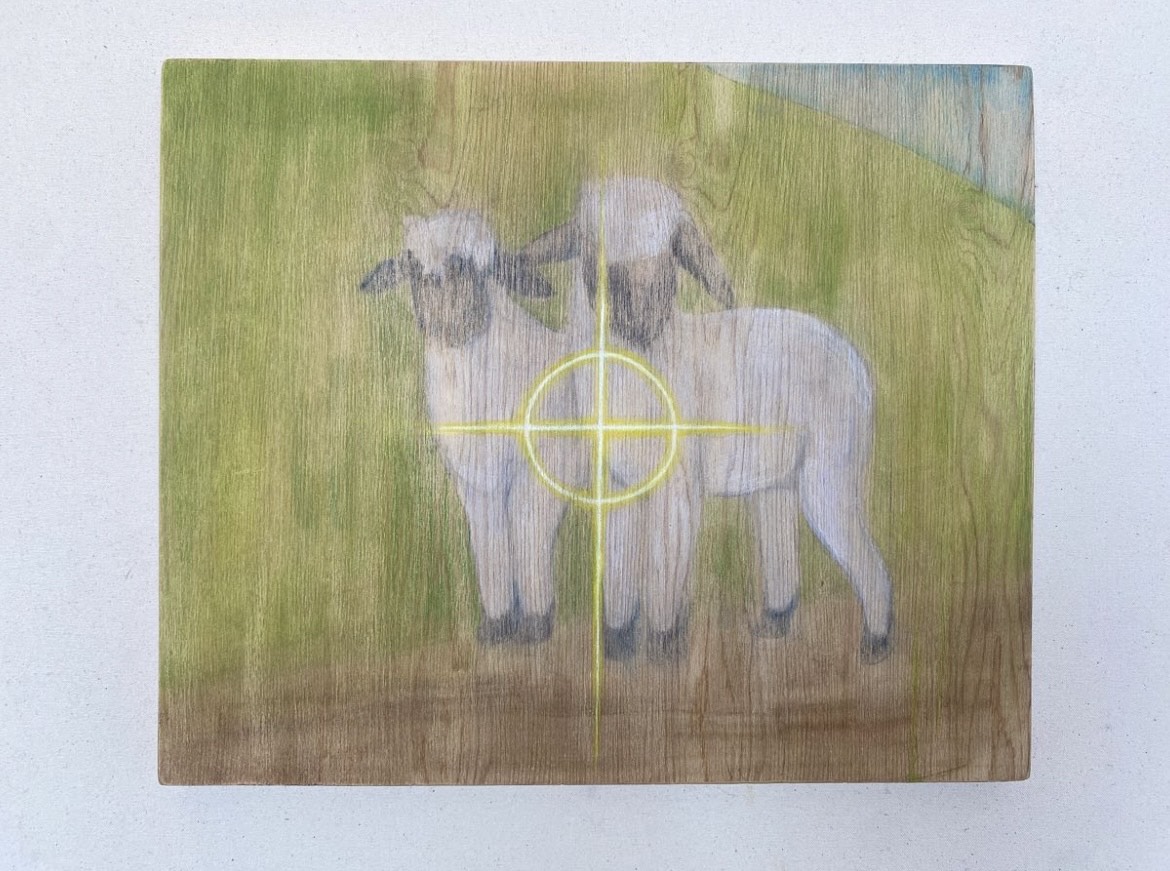

GT: I feel this push and pull when I look at your work across themes and the tension between the art and the viewer. A common theme in your works is subjects staring right at the viewer, whether that be a pair of lambs acknowledging their hunter, sad puppy eyes, a mattress salesman with a wide grin, or even the spikes of cactus-like forms poking outwards in caution. How much do you think about the audience's relationship to the work, if any?

SL: I think one thing I am constantly trying to grasp is some evocative feeling. I wanted the cactus piece to be visceral, so that whoever is looking at it can almost feel it with their hands, face, or something like that. So yeah, I do think of confrontation in that way but I don't think about it much further than that when I'm executing the piece. I want the pieces to stand alone by themselves because I think about them as a group a lot, which I don't think comes to a fault but I do want individual pieces to be strong and prompt a conversation with the viewer.

SL: This is my fifth or sixth year living in Chicago, and I think the distance has definitely helped give me an outside perspective, or maybe it's just time to be away from my upbringing. It has helped me look at the cultural environments there objectively, I guess. Still, I'm always tying in nostalgic veins through it. So, it's not totally objective. I know that, but I think it has really helped me reinforce crossroads, which I really try to illustrate in my work. I feel like I'm always playing on two different sides of something.

GT: I feel this push and pull when I look at your work across themes and the tension between the art and the viewer. A common theme in your works is subjects staring right at the viewer, whether that be a pair of lambs acknowledging their hunter, sad puppy eyes, a mattress salesman with a wide grin, or even the spikes of cactus-like forms poking outwards in caution. How much do you think about the audience's relationship to the work, if any?

SL: I think one thing I am constantly trying to grasp is some evocative feeling. I wanted the cactus piece to be visceral, so that whoever is looking at it can almost feel it with their hands, face, or something like that. So yeah, I do think of confrontation in that way but I don't think about it much further than that when I'm executing the piece. I want the pieces to stand alone by themselves because I think about them as a group a lot, which I don't think comes to a fault but I do want individual pieces to be strong and prompt a conversation with the viewer.

GT: Where do you find the most inspiration or guidance when you're in the early stages of making? Is it material, concept, or something you can see in your mind that you try to replicate?

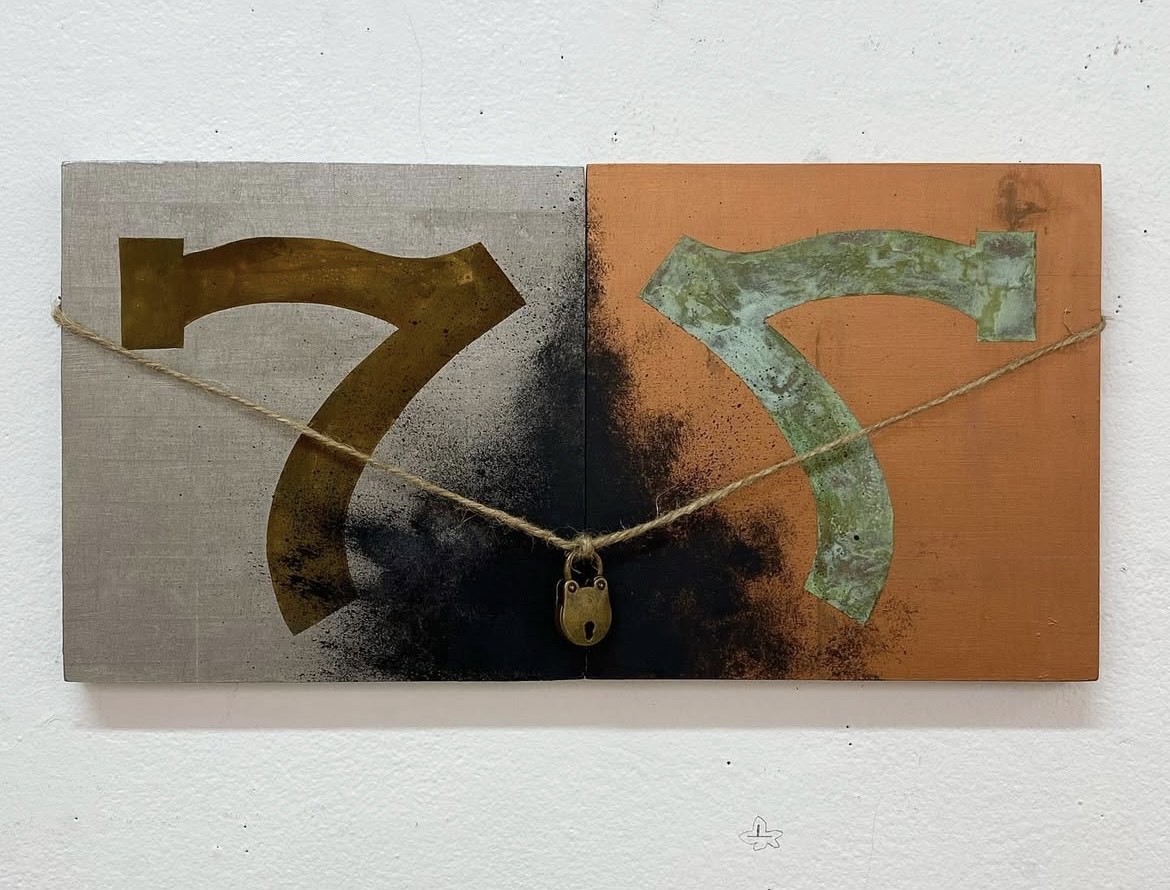

SL: It’s usually material unless it’s a painting or a drawing like the dog and the mattress salesman. But it’s usually the material. If I think about the concept too much going into a project, it mentally blocks me and slows down the actual making process. Because I use a lot of nuanced imagery, I feel like I put a lot of pressure on myself, giving myself this intense responsibility to have my concepts fully flushed out beforehand, but then the pressure debilitates me in a way. Lately, I’ve been trying to focus more on the materials. In the works, I do feel I reference the materials a lot themselves, like wood and rust and stuff like that. I know that the materials and motifs I use have this inherent irony, so the critique is relevant to the aesthetic. I think the critique is almost built into the aesthetic itself. When I think about it this way, I can execute the physical aspects of the work, and the concepts will fall into place.

GT: Speaking of materials and concept, I’d love to talk about the locks of hair and braids I’ve been seeing in your recent works that echo the sense of nostalgia and innocence. They also remind me of Victorian hair art. Is there any correlation there? What drew you to using hair? Is it real hair?

SL: It's synthetic hair! I think a lot of what I'm trying to do with this approach to surrealism is to personify these pieces I'm making a little bit and give them human attributes. The hair and the braids are, again, one of those things. It's a material that will do a lot of legwork for me. Pairing that with things like camouflage and bones is very juxtaposing, but it prompts a conversation of stuff I'm trying to stir up in my head. And with the hair, I feel I've been using it in a way that is sometimes restricted and sometimes free-flowing. I care a lot about my hair, and it's evolving into an identity marker in my work.

GT: And it's the same as your hair color!

SL: Yeah! My hair is so long that I should just start using my real hair in it. I've never said that it could be a placeholder for me in the work, but it could be.

SL: It’s usually material unless it’s a painting or a drawing like the dog and the mattress salesman. But it’s usually the material. If I think about the concept too much going into a project, it mentally blocks me and slows down the actual making process. Because I use a lot of nuanced imagery, I feel like I put a lot of pressure on myself, giving myself this intense responsibility to have my concepts fully flushed out beforehand, but then the pressure debilitates me in a way. Lately, I’ve been trying to focus more on the materials. In the works, I do feel I reference the materials a lot themselves, like wood and rust and stuff like that. I know that the materials and motifs I use have this inherent irony, so the critique is relevant to the aesthetic. I think the critique is almost built into the aesthetic itself. When I think about it this way, I can execute the physical aspects of the work, and the concepts will fall into place.

GT: Speaking of materials and concept, I’d love to talk about the locks of hair and braids I’ve been seeing in your recent works that echo the sense of nostalgia and innocence. They also remind me of Victorian hair art. Is there any correlation there? What drew you to using hair? Is it real hair?

SL: It's synthetic hair! I think a lot of what I'm trying to do with this approach to surrealism is to personify these pieces I'm making a little bit and give them human attributes. The hair and the braids are, again, one of those things. It's a material that will do a lot of legwork for me. Pairing that with things like camouflage and bones is very juxtaposing, but it prompts a conversation of stuff I'm trying to stir up in my head. And with the hair, I feel I've been using it in a way that is sometimes restricted and sometimes free-flowing. I care a lot about my hair, and it's evolving into an identity marker in my work.

GT: And it's the same as your hair color!

SL: Yeah! My hair is so long that I should just start using my real hair in it. I've never said that it could be a placeholder for me in the work, but it could be.

GT: Your work reminds me of Sally Mann's photography, focusing on the American South. Also, the images and scenes you create have this fleeting feeling like glimpsing a passing memory. I've found that your works bounce between having a discernable environment, such as lush pastures that are intimate and hazy and other times being void of comprehensible peripheries. How important is it for you to build out your environments? Is this something you tend to take into consideration?

SL: I tend to think about it in the context of my works as a whole. For example, when I'm writing a show proposal, one piece is one piece, but when you put them all together, it's going to become this whole conceptual narrative, and I aim for the environments of my subjects to emerge within this conceptual narrative. I do like to illustrate these environments with a sort of hazed detachment, in hopes of integrating notions of fleeting memories and recollection. But on the other hand, some subjects, in a pictorial space, do not necessarily need to be grounded in their environment.

GT: I love that idea of conceptual narrative as a whole and how we are glimpsing into a moment in time!

SL: I don’t feel the need to paint an image of a scene with a foreground, middle ground, and background. With the dog, I feel like that is all that’s necessary for the viewer to understand what environment it was in. I understand that I use images from a specific source of inspiration, but I don’t necessarily want to be making Texas fan art, and I want it to be adaptable.

SL: I tend to think about it in the context of my works as a whole. For example, when I'm writing a show proposal, one piece is one piece, but when you put them all together, it's going to become this whole conceptual narrative, and I aim for the environments of my subjects to emerge within this conceptual narrative. I do like to illustrate these environments with a sort of hazed detachment, in hopes of integrating notions of fleeting memories and recollection. But on the other hand, some subjects, in a pictorial space, do not necessarily need to be grounded in their environment.

GT: I love that idea of conceptual narrative as a whole and how we are glimpsing into a moment in time!

SL: I don’t feel the need to paint an image of a scene with a foreground, middle ground, and background. With the dog, I feel like that is all that’s necessary for the viewer to understand what environment it was in. I understand that I use images from a specific source of inspiration, but I don’t necessarily want to be making Texas fan art, and I want it to be adaptable.

GT: Yeah, absolutely. On the way over here, I was thinking about how you commonly use animals as your subjects. What draws you to them?

SL: Yeah, many animals have this built-in symbolism that I like. Animals carry this symbolism that you don’t need to tie to one particular animal or one specific face, I guess. And I think animals are a bit more approachable.

GT: We’ve touched on this a little, but how has your practice evolved over the years?

SL: When I first started art school, I didn’t realize this until I was looking back at my work, but my first year of art school, I was making work that is kind of aligned with what I’m doing now but somewhere in the middle I like, I don’t want to say derailed because I was in school, I was supposed to be exploring my options. I was doing a lot of abstract painting for a while. I love painting, but I’m not the type of painter who feels that it is a meditative process for them and that they can let the painting reveal itself to them. I tried to be that person for a very long time, and the process was not enjoyable for me. Then, I was drawn to working with these Southern motifs again, and I think that’s when I started doing more material play. I’ve always been drawn to mixed media stuff.

GT: We’ve touched on this a little, but how has your practice evolved over the years?

SL: When I first started art school, I didn’t realize this until I was looking back at my work, but my first year of art school, I was making work that is kind of aligned with what I’m doing now but somewhere in the middle I like, I don’t want to say derailed because I was in school, I was supposed to be exploring my options. I was doing a lot of abstract painting for a while. I love painting, but I’m not the type of painter who feels that it is a meditative process for them and that they can let the painting reveal itself to them. I tried to be that person for a very long time, and the process was not enjoyable for me. Then, I was drawn to working with these Southern motifs again, and I think that’s when I started doing more material play. I’ve always been drawn to mixed media stuff.

When I stopped putting such a high emphasis on paint, I think that’s when I finally let myself breathe, play, and experiment. That’s when the good stuff started coming out, I think. It just felt like a better process and a lot lower pressure and I had stuff I could identify with more. I often ask myself, “am I doing this because I think it’s cool or because it might be received well?” I currently have that conversation, too, because camouflage is a trendy thing to wear, so during my critique, people were bringing up fashion, which I expected, but it helped me realize that it is something that I need to be aware of in these images and how they're being used.

GT: Material histories are fascinating, and watching how they change and grow these meanings over time. When trying to make work that you identify with, are the themes of personal reflection and emotional intimacy, if any, planned or intuitive? Why do you think they resonate with you?

SL: I am definitely trying to do some personal reflection. Because of the nuances that my imagery can kind of play into, there are these throughlines of critique in my work. I am critiquing this place I am from, but it’s also only from my viewpoint, so I think I should be critiquing myself in a sense. I think that’s why I feel inclined to put myself in the suit; it’s almost like a, I almost want to say, a humiliation ritual. I know it’s not, but I almost think of it like that. I am a product of this space and can’t pretend I’m not.

GT: Material histories are fascinating, and watching how they change and grow these meanings over time. When trying to make work that you identify with, are the themes of personal reflection and emotional intimacy, if any, planned or intuitive? Why do you think they resonate with you?

SL: I am definitely trying to do some personal reflection. Because of the nuances that my imagery can kind of play into, there are these throughlines of critique in my work. I am critiquing this place I am from, but it’s also only from my viewpoint, so I think I should be critiquing myself in a sense. I think that’s why I feel inclined to put myself in the suit; it’s almost like a, I almost want to say, a humiliation ritual. I know it’s not, but I almost think of it like that. I am a product of this space and can’t pretend I’m not.

GT: I can see how that message is coming through, especially with the fingers and limbs tied to the ground and the performance aspect of trying to escape but being unable to separate. Lastly, is there anything you’re looking forward to that you’d like to share?

SL: I am very excited about spring and the art fair season. I think it awakens something in me. I love seeing a bunch of my artist friends and EXPO weekend. It’s so fun, and I feel so glamorous during EXPO weekend. I like to see what’s going on in the contemporary canon.

GT: How fun! This has been lovely; thank you so much!

SL: Thank you!

SL: I am very excited about spring and the art fair season. I think it awakens something in me. I love seeing a bunch of my artist friends and EXPO weekend. It’s so fun, and I feel so glamorous during EXPO weekend. I like to see what’s going on in the contemporary canon.

GT: How fun! This has been lovely; thank you so much!

SL: Thank you!

Sara’s website: https://sara-lam.com/.