INTERVIEW WITH SHERIDYN VILLARREAL

By Rebecka Öhrström Kann 5/11/2023

Rebecka Ohrstrom Kann: You grew up in San Antonio, Texas, but currently live and work in Chicago. I’m curious to hear how these two places have affected your practice and interests as a curator and researcher?

Sheridyn Villarreal: I always love any opportunity to talk about San Antonio, though it brings about a lot of complicated feelings. I really loved my childhood in San Antonio and felt that I was in a very protective and supportive, queer artistic bubble as a young person, which was so wonderful. But it's also very at odds with the rhetoric and the conservative politics that govern the state at large and spaces outside of that bubble. My reason for [eventually] leaving San Antonio was because I wanted to pursue my college-level education in the arts, and I felt that Chicago gave me the best opportunity to do so that was within my ability to pursue. I do think about San Antonio often, and as I get older and spend more time in the field, I recognize its impact on my thinking as a person and also my interests in art. I grew up bilingual, [attending] school in both English and Spanish at different points in my education and was fortunate enough to grow up in a very diverse city.

Sheridyn Villarreal: I always love any opportunity to talk about San Antonio, though it brings about a lot of complicated feelings. I really loved my childhood in San Antonio and felt that I was in a very protective and supportive, queer artistic bubble as a young person, which was so wonderful. But it's also very at odds with the rhetoric and the conservative politics that govern the state at large and spaces outside of that bubble. My reason for [eventually] leaving San Antonio was because I wanted to pursue my college-level education in the arts, and I felt that Chicago gave me the best opportunity to do so that was within my ability to pursue. I do think about San Antonio often, and as I get older and spend more time in the field, I recognize its impact on my thinking as a person and also my interests in art. I grew up bilingual, [attending] school in both English and Spanish at different points in my education and was fortunate enough to grow up in a very diverse city.

San Antonio is a majority Latino city within the United States, and historically has been for a very long time. I didn't recognise until I was older and spent more time away just how much the city has fostered the creation of an utterly syncretic culture all its own. Being away from it, I appreciate that it isn't inherent in other places. And so I think that has partly informed my interest in artists who are working at the intersections of identity, experience, form, and materiality. I think I’m interested in those intersections precisely because of my upbringing being [at the] intersection of a lot of different cultural influences and identities that I am consistently drawn to.

ROK: I feel like sometimes you just need the distance to reflect and appreciate places in very different ways. I realized I should probably ask if you could talk a little bit about yourself and your curatorial interests as well.

SV: I think, like you just said, hindsight and having just some sort of distance from a thing can sometimes make you see it more clearly or give you a new insight that you can't always perceive when you're in the middle of what it is that you're doing. And I think in the past year, that I've had the opportunity to curate more shows and more exhibitions, especially with solo presentations of work by individual artists. I'm starting to also recognise these underlying interests that I have that maybe I didn't realize before. It’s become very apparent to me that I'm very interested in the artist's process that transpires in the studio, you know, the craft that goes into an artist's practice. So, I definitely gravitate towards work, which makes me wonder, you know, “Oh, how did this come to be?” in a very material sense of like, truly, how was this crafted? I think it's both exciting when you can kind of recognise and tease out aspects of craftsmanship that you recognise, but then it's even more exciting when [you] can't even identify the technique or the form that [you’re] seeing. I just find that very exciting. And so I’ve definitely come to realize that I'm very interested in the artist's process, whether that transpires in the studio or out, prior to arriving in an exhibition context.

SV: I think, like you just said, hindsight and having just some sort of distance from a thing can sometimes make you see it more clearly or give you a new insight that you can't always perceive when you're in the middle of what it is that you're doing. And I think in the past year, that I've had the opportunity to curate more shows and more exhibitions, especially with solo presentations of work by individual artists. I'm starting to also recognise these underlying interests that I have that maybe I didn't realize before. It’s become very apparent to me that I'm very interested in the artist's process that transpires in the studio, you know, the craft that goes into an artist's practice. So, I definitely gravitate towards work, which makes me wonder, you know, “Oh, how did this come to be?” in a very material sense of like, truly, how was this crafted? I think it's both exciting when you can kind of recognise and tease out aspects of craftsmanship that you recognise, but then it's even more exciting when [you] can't even identify the technique or the form that [you’re] seeing. I just find that very exciting. And so I’ve definitely come to realize that I'm very interested in the artist's process, whether that transpires in the studio or out, prior to arriving in an exhibition context.

R: You want to know the recipe.

SV: I'm very interested in the recipe. I just get excited by those layers of conceptualization and experimentation and I want to know more.

ROK: I love the layers. I was curious also, which artists, writers, academics, curators, or other creative thinkers have influenced this interest or your curatorial practice in general?

SV: You know, this came across my inbox earlier today, which was an email that made mention of [the curator] Helen Molesworth, coming to Chicago to promote a book of her writing. And while I wouldn't say I know the breadth of her work in studious detail, there is a quote about her practice that resonated with me when I read it a while back ago. It was [in] an article interviewing multiple artists who had worked with Helen Molesworth. They were kind of doing an appraisal on her career as a curator, and one thing that really stuck out to me was an artist, Karon Davis, who said [of Molesworth] “she is an artist’s curator. Always the artist first.” I found that really admirable, and something that, if I can be anything, I would want to be that; an ally and an advocate.

ROK: I think that makes a lot of sense with the shows that you've produced. I think you're really taking the time to not just include the artist’s work in the show but also make sure they feel represented in that space as well. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about your curatorial approach as well. What sort of things do you think about when you're curating?

SV: Some of the things that I think about in my practice is, as I said, I'm really interested in the process and the experience that happens in the act of making. I'm really interested in the process taking place in the artist's studio, and everything that goes into the artist's practice prior to arriving in the venue, I think, is so fascinating. I'm definitely very dialogue-heavy with the artists that I work with. I really like to take the time to find out what opportunities there are for collaboration, find out what the artist's goals may be with the exhibition, besides exhibiting their work. If they have an interest like “I’ve really been wanting to do this programme, and I haven't had the chance to do it”, or “I’ve really been wanting to do this performance, but I haven't had the venue or the funding to do it”. So I’ve been very dialogue intensive in my curatorial methods up to this point. I've worked exclusively with emerging and living artists, of course, and I would like to continue working with living artists, as well as those who are maybe emerging to mid-career because it allows for that kind of dynamic, mutual relationship.

SV: I'm very interested in the recipe. I just get excited by those layers of conceptualization and experimentation and I want to know more.

ROK: I love the layers. I was curious also, which artists, writers, academics, curators, or other creative thinkers have influenced this interest or your curatorial practice in general?

SV: You know, this came across my inbox earlier today, which was an email that made mention of [the curator] Helen Molesworth, coming to Chicago to promote a book of her writing. And while I wouldn't say I know the breadth of her work in studious detail, there is a quote about her practice that resonated with me when I read it a while back ago. It was [in] an article interviewing multiple artists who had worked with Helen Molesworth. They were kind of doing an appraisal on her career as a curator, and one thing that really stuck out to me was an artist, Karon Davis, who said [of Molesworth] “she is an artist’s curator. Always the artist first.” I found that really admirable, and something that, if I can be anything, I would want to be that; an ally and an advocate.

ROK: I think that makes a lot of sense with the shows that you've produced. I think you're really taking the time to not just include the artist’s work in the show but also make sure they feel represented in that space as well. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about your curatorial approach as well. What sort of things do you think about when you're curating?

SV: Some of the things that I think about in my practice is, as I said, I'm really interested in the process and the experience that happens in the act of making. I'm really interested in the process taking place in the artist's studio, and everything that goes into the artist's practice prior to arriving in the venue, I think, is so fascinating. I'm definitely very dialogue-heavy with the artists that I work with. I really like to take the time to find out what opportunities there are for collaboration, find out what the artist's goals may be with the exhibition, besides exhibiting their work. If they have an interest like “I’ve really been wanting to do this programme, and I haven't had the chance to do it”, or “I’ve really been wanting to do this performance, but I haven't had the venue or the funding to do it”. So I’ve been very dialogue intensive in my curatorial methods up to this point. I've worked exclusively with emerging and living artists, of course, and I would like to continue working with living artists, as well as those who are maybe emerging to mid-career because it allows for that kind of dynamic, mutual relationship.

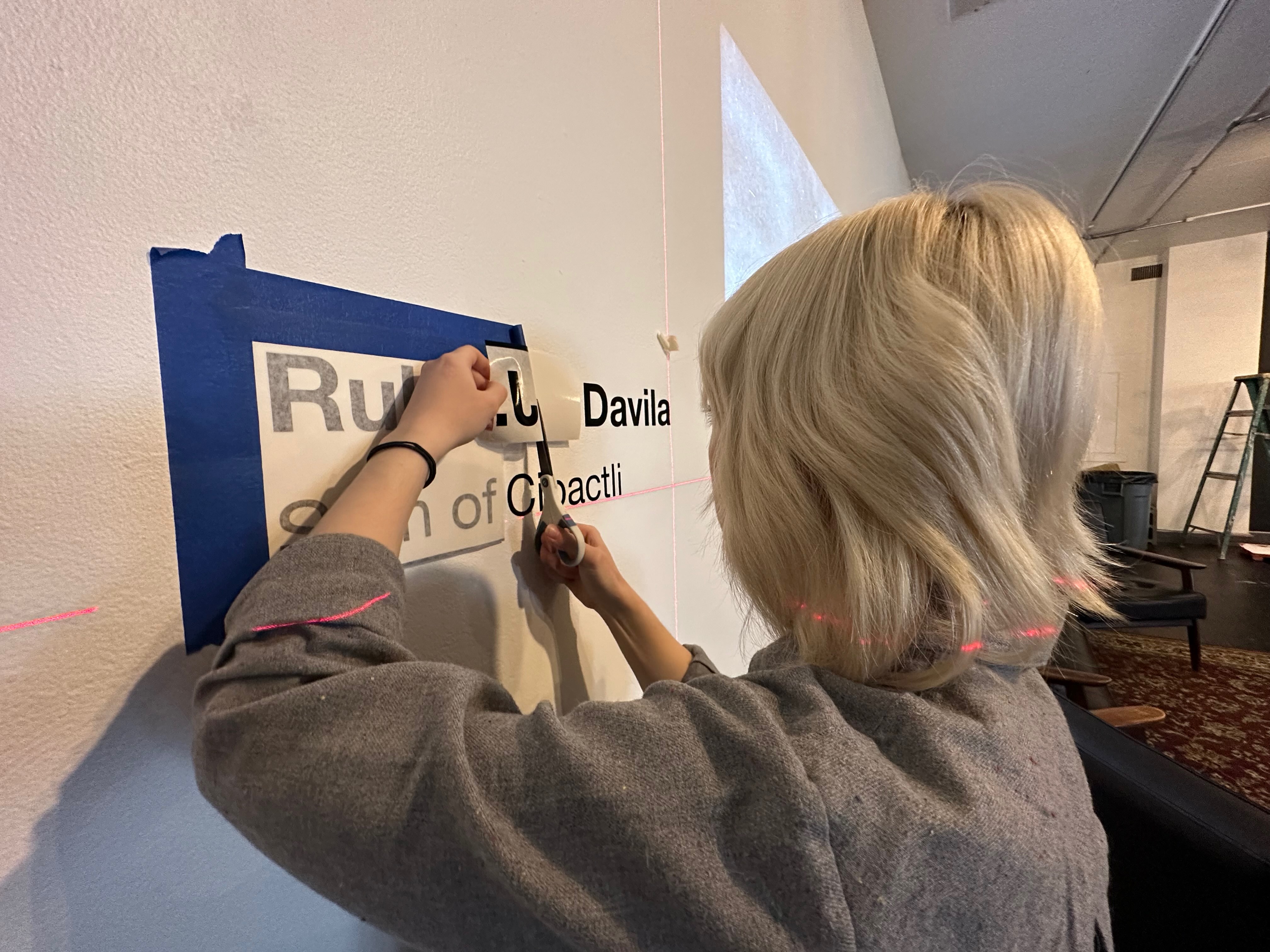

Another thing I spend a lot of time thinking about is the visitor. I got my start from the very beginning in visitor-facing and labour intensive roles. Before I really knew that I wanted to pursue art history I had the opportunity to work in an artist's residency. I did a summer internship at an artist residency in San Antonio, where I got to see the artists actually ideate and make their work in the studio. And then later my first real foray into the professional art industry was installing art as an art handler and preparator. I've also spent a lot of time in front-facing roles and then also installing the artwork on the back end, working with curators and artists to execute the plans that they have laid. And I think that that really gives you such a unique appreciation for the experience of the visitor, and the experience of all of the people besides curators and artists that not just bring the exhibit together, but also maintain the exhibit for however many days or weeks or months it’s up. I think that is so so important to how I think about shows and how I think about the visitor's spatial and environmental experience or how the work may exist in a space over time. And I truly value that so much. I think it gives me a lot of insight not only into the other labour that goes into putting an exhibit up and maintaining it but also interpreting that show to the public and practical aspects of exhibition making.

ROK: I definitely see that, especially as someone who has worked alongside you both as a coworker and an artist. Exhibition-making is also such a collaborative process and sometimes it’s easy to forget the labour that goes into making and maintaining a show.

SV: Yeah, I know that, to some extent, when people think of exhibition-making, the most prominent players they might think of would be a curator or an artist, but there's not a lot of visibility for the labour of installers, registrars or folks who are mount-makers and conservators. And then, of course, visitor service associates who arguably spend more time in the gallery with the work than anyone and observing the myriad of ways that visitors interact with those exhibits. And if I can be an artist-ally, an advocate, if I can help them get closer to a personal goal that they have, and if I can also achieve a positive and insightful experience for the visitor AND for the crew who actually works on bringing the show to fruition, then, that's all I can hope for. That's what I can aspire to.

ROK: I definitely see that, especially as someone who has worked alongside you both as a coworker and an artist. Exhibition-making is also such a collaborative process and sometimes it’s easy to forget the labour that goes into making and maintaining a show.

SV: Yeah, I know that, to some extent, when people think of exhibition-making, the most prominent players they might think of would be a curator or an artist, but there's not a lot of visibility for the labour of installers, registrars or folks who are mount-makers and conservators. And then, of course, visitor service associates who arguably spend more time in the gallery with the work than anyone and observing the myriad of ways that visitors interact with those exhibits. And if I can be an artist-ally, an advocate, if I can help them get closer to a personal goal that they have, and if I can also achieve a positive and insightful experience for the visitor AND for the crew who actually works on bringing the show to fruition, then, that's all I can hope for. That's what I can aspire to.

ROK: I know you just finished up your curatorial residency at Elastic Arts, where you've been curating shows for the past year, which is a very unique space to curate for since their primary focus is on performance and music. And so I’m curious if you could talk a little bit about your experience curating in this dynamic environment that functions so differently, as opposed to, you know, like the standard white cube.

SV: Oh, my gosh, that experience has been the absolute best, and I think the best for me as a young curator because, as you said, Elastic Arts is a space that has been around in Chicago for 25 years, is a wonderful, not just locus for experimental, emerging forms of art, especially in the realm of performance, music, dance and poetry, you name it. I think that's actually been really valuable for me as a young curator because I definitely have spent a lot of time in museum spaces where space has been oriented towards these static, controlled, non-dynamic environments that really prioritize the static object or the static image. And so Elastic Arts being the exact opposite of that, has actually been great. Not only has it been a really rigorous practice in creative problem solving, I think it's also been a very rigorous practice in communication. Not only was every show an opportunity to communicate with the stakeholders in the space itself, the staff who work at Elastic Arts and their various needs for the space. But besides those folks, there's also a huge quantity of performers, dancers, musicians, and event producers that actively use the space to put on their own performances and their own events. And so, I think that it's been a rigorous practice in communication and collaboration, and honestly, listening to people's needs and their various uses of the space. Especially folks who are coming from all sorts of different perspectives, maybe people who, you know, are so involved and devoted to their world of performing music or dance that they maybe aren't thinking about how to coexist with a visual art gallery and the same way that I would think about it. But it also challenged me to put myself out of my own mindset and think about how these two very different forms of art can coexist in a way that's safe for both of them to express themselves to the fullest extent. Not anything that's going to impede the performance but also nothing that's going to jeopardize or impede the authentic expression of the exhibition gallery. I think that's so valuable for someone who's only just now beginning to be able to realise these curatorial projects to be genuinely put in a situation where there are a lot of really challenging, dynamic, exciting factors that are not the norm in a white cube gallery. And so, it's been a very creative process, but it also demanded the utmost communication and collaboration and putting myself outside of the perspective of the white cube gallery ethos.

R: Yeah, I think it's so interesting that you can really stumble upon the works, in a very different way than you would in a normal white cube. Like either you're there to see the exhibition specifically, or perhaps you came there to see a performance and then you realize there's this really lovely exhibition on display that you weren’t aware of beforehand.

SV: That also is such a great quality. And when going about choosing the kind of work that's going to be in the visual gallery, I'm also thinking about what kind of performances are going to be happening in the space, what kind of events are going to be taking place, and what the experience will be to have the works of art in the visual gallery to share that space. How that can coexist, and maybe even have a dialogue with the performances. And when does that dialogue happen? Thankfully, I feel like sometimes we're able to get that special magic, where actually people who, as you said, are maybe going because they're there to see a specific performance, feel like their overall experience is heightened by the artwork, which, while being its own individual entity, really complements the given programme of performances. So they can have this unexpected dialogue, which is so exciting.

SV: Oh, my gosh, that experience has been the absolute best, and I think the best for me as a young curator because, as you said, Elastic Arts is a space that has been around in Chicago for 25 years, is a wonderful, not just locus for experimental, emerging forms of art, especially in the realm of performance, music, dance and poetry, you name it. I think that's actually been really valuable for me as a young curator because I definitely have spent a lot of time in museum spaces where space has been oriented towards these static, controlled, non-dynamic environments that really prioritize the static object or the static image. And so Elastic Arts being the exact opposite of that, has actually been great. Not only has it been a really rigorous practice in creative problem solving, I think it's also been a very rigorous practice in communication. Not only was every show an opportunity to communicate with the stakeholders in the space itself, the staff who work at Elastic Arts and their various needs for the space. But besides those folks, there's also a huge quantity of performers, dancers, musicians, and event producers that actively use the space to put on their own performances and their own events. And so, I think that it's been a rigorous practice in communication and collaboration, and honestly, listening to people's needs and their various uses of the space. Especially folks who are coming from all sorts of different perspectives, maybe people who, you know, are so involved and devoted to their world of performing music or dance that they maybe aren't thinking about how to coexist with a visual art gallery and the same way that I would think about it. But it also challenged me to put myself out of my own mindset and think about how these two very different forms of art can coexist in a way that's safe for both of them to express themselves to the fullest extent. Not anything that's going to impede the performance but also nothing that's going to jeopardize or impede the authentic expression of the exhibition gallery. I think that's so valuable for someone who's only just now beginning to be able to realise these curatorial projects to be genuinely put in a situation where there are a lot of really challenging, dynamic, exciting factors that are not the norm in a white cube gallery. And so, it's been a very creative process, but it also demanded the utmost communication and collaboration and putting myself outside of the perspective of the white cube gallery ethos.

R: Yeah, I think it's so interesting that you can really stumble upon the works, in a very different way than you would in a normal white cube. Like either you're there to see the exhibition specifically, or perhaps you came there to see a performance and then you realize there's this really lovely exhibition on display that you weren’t aware of beforehand.

SV: That also is such a great quality. And when going about choosing the kind of work that's going to be in the visual gallery, I'm also thinking about what kind of performances are going to be happening in the space, what kind of events are going to be taking place, and what the experience will be to have the works of art in the visual gallery to share that space. How that can coexist, and maybe even have a dialogue with the performances. And when does that dialogue happen? Thankfully, I feel like sometimes we're able to get that special magic, where actually people who, as you said, are maybe going because they're there to see a specific performance, feel like their overall experience is heightened by the artwork, which, while being its own individual entity, really complements the given programme of performances. So they can have this unexpected dialogue, which is so exciting.

ROK: This is kind of a switch to a different topic, but I know we’ve talked a little bit together about your interests in time-based media, you know, things like video games and film and internet art. And so, I was curious if you could talk about time-based media that excites you.

SV: Sure. That's a good question. And I still think it's quite funny because I don't have much of an explanation for it because you might think that given my interest in new media art, which, you know, runs the gamut, from film to video games, to internet art, that I would come from a very online childhood. Of course, I am of an online generation, but actually, my upbringing was not particularly online. I was raised by a single parent who was actually fairly restrictive about my access to the internet, which is a whole different story. But nonetheless, I was not a chronically online child and I was actually forbidden from playing video games and my access to social platforms tightly monitored. So I wouldn't describe myself as a very tech-literate person. Of course, you would probably disagree, and other people around me would probably disagree because, by virtue of my interest in new media art, I am educated on a lot of these concepts. But a lot of my familiarity and my knowledge about it doesn't really necessarily come from my own personal experience because I was not really allowed to be a very online young person. I don't know if it’s something to do with the fact that it’s kind of outside my own experience that interests me. Maybe that is, to some extent, why it has some novelty to it. I don't know, maybe time will tell me the answer to that one.

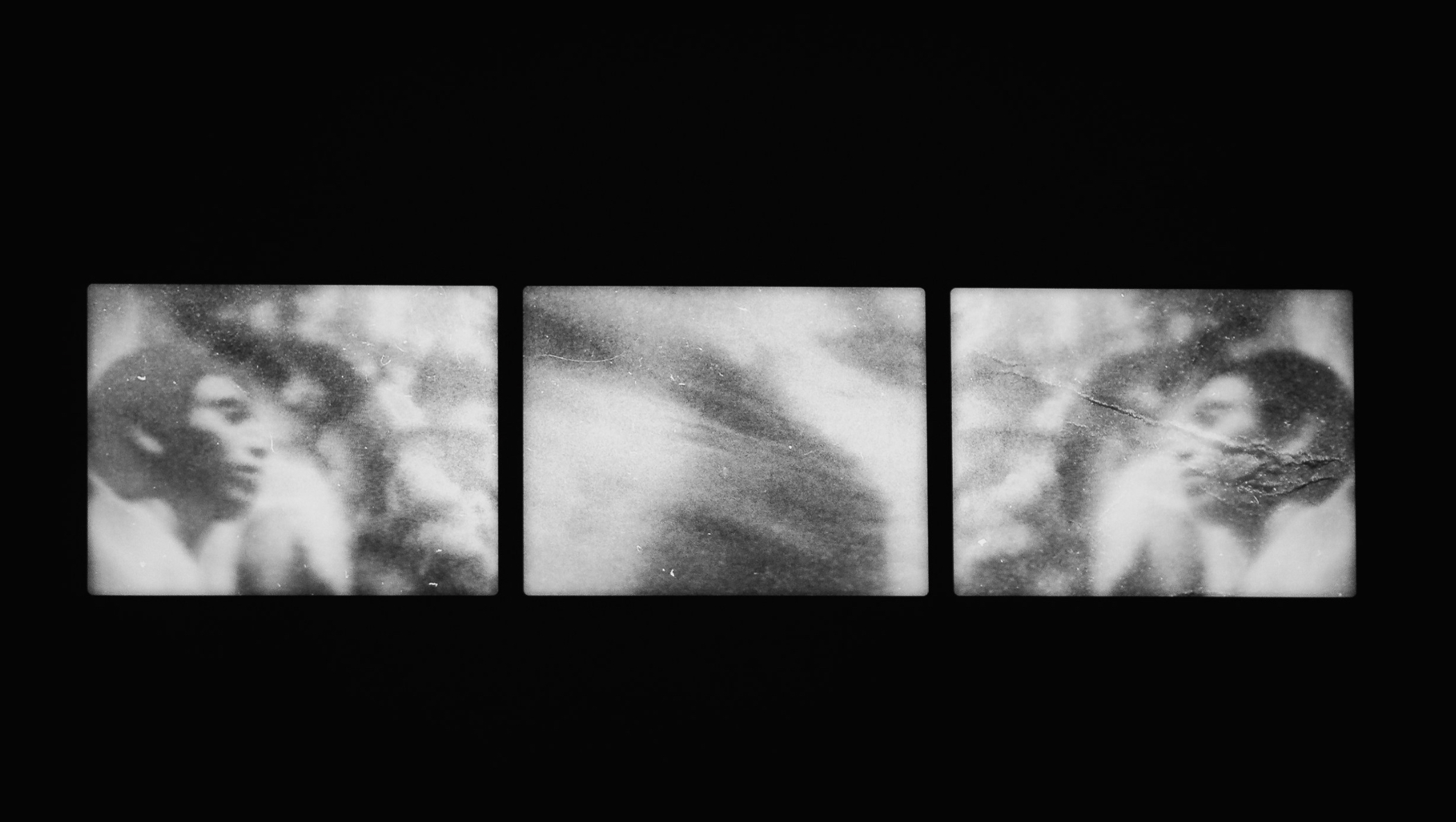

But I have always had a pervasive interest in science fiction and speculative fiction. Which I came to understand later was that these fantastical, or technological premises usually function to interrogate the boundaries of what it is to be human and the human experience. So my initial gravitation toward artists working in new media is that a great many are likewise kind of prodding at the boundaries that seek to distinguish different fields or supposed binaries. I mean, new media itself is already prodding the boundary of what is considered art, what is considered conventional art or conventional art materials. It’s already challenging the boundary of what is and what can be art. And so I think, therein lies my interests in new media, film, and time-based art.

Time-based art especially has this dynamic, transportation over time, and I think it's also, because of my interest in the process, that in the kind of experiential quality of an interactive work of art like a video game-based work or film and performance, there is this, realm of transformation that occurs in this prolonged durational experience of the work of art. And, again, that intersection, that ambiguity where something new or unique or transformational can occur as always, is likely what I'm chasing.

SV: Sure. That's a good question. And I still think it's quite funny because I don't have much of an explanation for it because you might think that given my interest in new media art, which, you know, runs the gamut, from film to video games, to internet art, that I would come from a very online childhood. Of course, I am of an online generation, but actually, my upbringing was not particularly online. I was raised by a single parent who was actually fairly restrictive about my access to the internet, which is a whole different story. But nonetheless, I was not a chronically online child and I was actually forbidden from playing video games and my access to social platforms tightly monitored. So I wouldn't describe myself as a very tech-literate person. Of course, you would probably disagree, and other people around me would probably disagree because, by virtue of my interest in new media art, I am educated on a lot of these concepts. But a lot of my familiarity and my knowledge about it doesn't really necessarily come from my own personal experience because I was not really allowed to be a very online young person. I don't know if it’s something to do with the fact that it’s kind of outside my own experience that interests me. Maybe that is, to some extent, why it has some novelty to it. I don't know, maybe time will tell me the answer to that one.

But I have always had a pervasive interest in science fiction and speculative fiction. Which I came to understand later was that these fantastical, or technological premises usually function to interrogate the boundaries of what it is to be human and the human experience. So my initial gravitation toward artists working in new media is that a great many are likewise kind of prodding at the boundaries that seek to distinguish different fields or supposed binaries. I mean, new media itself is already prodding the boundary of what is considered art, what is considered conventional art or conventional art materials. It’s already challenging the boundary of what is and what can be art. And so I think, therein lies my interests in new media, film, and time-based art.

Time-based art especially has this dynamic, transportation over time, and I think it's also, because of my interest in the process, that in the kind of experiential quality of an interactive work of art like a video game-based work or film and performance, there is this, realm of transformation that occurs in this prolonged durational experience of the work of art. And, again, that intersection, that ambiguity where something new or unique or transformational can occur as always, is likely what I'm chasing.

ROK: It’s so interesting how science fiction serves as many people's first introduction to post-humanism as kids.

SV: Yeah, definitely. Post-humanism was a natural kind of arrival from my childhood love of science fiction and ultimately, again, prods at questions about the boundaries of life, existence and ideas of embodiment. Especially as a queer, gender non-conforming person, who has always kind of had questions about my own gender experience and gender presentation, I also think, like many queer folks who were also really interested in science fiction, that science fiction also kind of provided a way to express or act out my queer identity in a concealed or permissive way. I mean, everything is queer in a speculative science fiction world that is exclusively interested in bending binary boundaries and transgressing or questioning them. So I do know that in my experience as a queer person, science fiction definitely was this kind of escapist place for me as a young person and continues to propel my interest in post-humanism and its use to question binaries and to really propose not simply the dissolution of binaries, but also the transformative potential induced by the dissolution.

ROK: What’s one piece of advice someone has given you that you’ve found to be true?

SV: That's a funny one [laughs]. I actually had a conversation with someone yesterday and I actually told them this story, too. When I was in high school, because I went to a very strange high school in the state of Texas, I went to a free, publicly funded Fine Arts intensive High School, which seems like it should not exist in the state of Texas. But miraculously, it did. And so, while I was there, I had a myriad of painting and drawing instructors, and actually, this person was not a particular favourite instructor of mine, I'd say they probably were, you know, my least favourite instructor that I had in art. But the one thing he did say that I, you know, I stand by, was that he said: “You know, no matter what it is, no matter what colour it is, even if it's just, you know, black paint, always finish the edges of your canvases.” So if you're painting, you know, your image on the canvas, and you have stray paint strokes on the edges, he said, “if you do nothing else, just, you know, finish the edges of the painting, it'll make it look a million times better, or more polished”, or something to that extent. And, I don't know how much utility I apply since I'm not, you know, actively painting anymore. But I think that's pretty solid advice. It never hurts to finish your edges, it never hurts to put in just a little bit of effort to make those small details look nice. It goes a long way to the overall presentation, especially since I've been installing a lot of artwork myself and I've worked with a lot of artists to install their artwork, I always put a lot of care into other people's artwork and I feel like I obsess over the details of taking care when installing folks artwork and how it's going to be treated in the space. And I'm willing to go a little extra effort to, you know, take care of someone's work and make sure that it is how they would want it to be treated and exhibited and interacted with.

ROK: I feel like that’s very full circle to everything you’ve said about wanting to have a genuine relationship with the artists that you're working with and really making sure that not only peoples’ art and ideas but also their labour is felt and heard in the space as well. Thank you for sharing that.

SV: Definitely [laughs]. I don't think I remember any other thing he ever said to me, but I remember that.

SV: Yeah, definitely. Post-humanism was a natural kind of arrival from my childhood love of science fiction and ultimately, again, prods at questions about the boundaries of life, existence and ideas of embodiment. Especially as a queer, gender non-conforming person, who has always kind of had questions about my own gender experience and gender presentation, I also think, like many queer folks who were also really interested in science fiction, that science fiction also kind of provided a way to express or act out my queer identity in a concealed or permissive way. I mean, everything is queer in a speculative science fiction world that is exclusively interested in bending binary boundaries and transgressing or questioning them. So I do know that in my experience as a queer person, science fiction definitely was this kind of escapist place for me as a young person and continues to propel my interest in post-humanism and its use to question binaries and to really propose not simply the dissolution of binaries, but also the transformative potential induced by the dissolution.

ROK: What’s one piece of advice someone has given you that you’ve found to be true?

SV: That's a funny one [laughs]. I actually had a conversation with someone yesterday and I actually told them this story, too. When I was in high school, because I went to a very strange high school in the state of Texas, I went to a free, publicly funded Fine Arts intensive High School, which seems like it should not exist in the state of Texas. But miraculously, it did. And so, while I was there, I had a myriad of painting and drawing instructors, and actually, this person was not a particular favourite instructor of mine, I'd say they probably were, you know, my least favourite instructor that I had in art. But the one thing he did say that I, you know, I stand by, was that he said: “You know, no matter what it is, no matter what colour it is, even if it's just, you know, black paint, always finish the edges of your canvases.” So if you're painting, you know, your image on the canvas, and you have stray paint strokes on the edges, he said, “if you do nothing else, just, you know, finish the edges of the painting, it'll make it look a million times better, or more polished”, or something to that extent. And, I don't know how much utility I apply since I'm not, you know, actively painting anymore. But I think that's pretty solid advice. It never hurts to finish your edges, it never hurts to put in just a little bit of effort to make those small details look nice. It goes a long way to the overall presentation, especially since I've been installing a lot of artwork myself and I've worked with a lot of artists to install their artwork, I always put a lot of care into other people's artwork and I feel like I obsess over the details of taking care when installing folks artwork and how it's going to be treated in the space. And I'm willing to go a little extra effort to, you know, take care of someone's work and make sure that it is how they would want it to be treated and exhibited and interacted with.

ROK: I feel like that’s very full circle to everything you’ve said about wanting to have a genuine relationship with the artists that you're working with and really making sure that not only peoples’ art and ideas but also their labour is felt and heard in the space as well. Thank you for sharing that.

SV: Definitely [laughs]. I don't think I remember any other thing he ever said to me, but I remember that.