Published by GIselle Torres 7/8/2024

Giselle Torres: How has the world around you informed the way you approach your work?

Taylor Allmon: There’s probably a number of ways that I could answer that, but I’ll start with an anecdote of sorts. I distinctly remember seventh grade as the year that I started making work about slavery, race, and death. There were a few pieces that I made, but the most overt was a sort of crude bricolage about the Scottsboro boys. I had printed and torn up some images, glued them down with modge podge or something similar, and painted the hand of a skeleton as if it were tearing through the canvas. I remember my art teacher looking at the piece and saying that it was “very exciting,” because it was one of the first times that we were being given true leeway in our class assignments, and that was what I came up with. So, although I look back on it now and think, “that was crude and corny,” I do think she might’ve realized that I was starting down a very thematically ripe path. That was a full decade ago, but I’m still on that path today and probably will be for the rest of my life.

All of that is to say that middle school, which was 2013-2016 for me, were the years that I came to the full realization that I, or we, are in such a serious predicament. Nationally and globally. These were the formative years of the Black Lives Matter Movement, and I was taking in all of the names and headlines at the same time that I was dealing with the personal challenges that often come with being a racial minority at a predominantly white school. These feel almost like buzzwords now, but I did and do feel a sense of urgency in my work, and I do feel called to bear witness. I hate to even mention Kamala Harris and the coconut tree, but my mind went there. I’m constantly thinking about the people and events that have led us to where we are now. I do try to keep my work in step with current events in some aspects, or actually I do so out of necessity. It’s become a way for me to process all of these traumatic things that are going on and channel my emotions into something that isn’t totally self destructive. It’s also the best way that I personally know how to honor and memorialize the deceased. I don’t like ignorance, and because there are so many people who want to actively deny and conceal history, particularly where it concerns Black enslavement, sacrifice, and subjugation, I’m insistent on keeping those things at the forefront of my work.

Taylor Allmon: There’s probably a number of ways that I could answer that, but I’ll start with an anecdote of sorts. I distinctly remember seventh grade as the year that I started making work about slavery, race, and death. There were a few pieces that I made, but the most overt was a sort of crude bricolage about the Scottsboro boys. I had printed and torn up some images, glued them down with modge podge or something similar, and painted the hand of a skeleton as if it were tearing through the canvas. I remember my art teacher looking at the piece and saying that it was “very exciting,” because it was one of the first times that we were being given true leeway in our class assignments, and that was what I came up with. So, although I look back on it now and think, “that was crude and corny,” I do think she might’ve realized that I was starting down a very thematically ripe path. That was a full decade ago, but I’m still on that path today and probably will be for the rest of my life.

All of that is to say that middle school, which was 2013-2016 for me, were the years that I came to the full realization that I, or we, are in such a serious predicament. Nationally and globally. These were the formative years of the Black Lives Matter Movement, and I was taking in all of the names and headlines at the same time that I was dealing with the personal challenges that often come with being a racial minority at a predominantly white school. These feel almost like buzzwords now, but I did and do feel a sense of urgency in my work, and I do feel called to bear witness. I hate to even mention Kamala Harris and the coconut tree, but my mind went there. I’m constantly thinking about the people and events that have led us to where we are now. I do try to keep my work in step with current events in some aspects, or actually I do so out of necessity. It’s become a way for me to process all of these traumatic things that are going on and channel my emotions into something that isn’t totally self destructive. It’s also the best way that I personally know how to honor and memorialize the deceased. I don’t like ignorance, and because there are so many people who want to actively deny and conceal history, particularly where it concerns Black enslavement, sacrifice, and subjugation, I’m insistent on keeping those things at the forefront of my work.

GT: What led you to focus on painting as your sole medium? Have you dabbled in other mediums before?

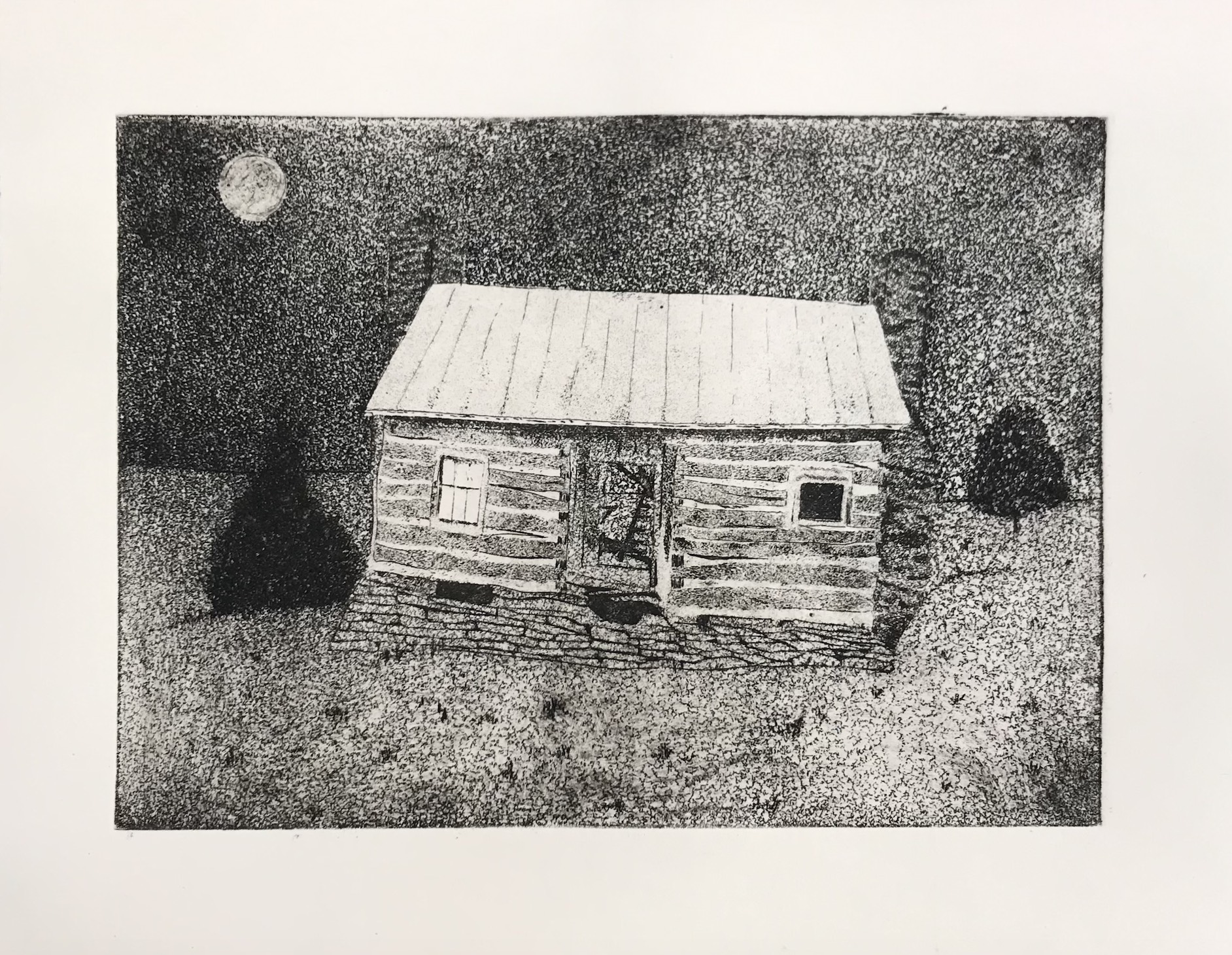

TA: I wouldn’t say that painting is my sole medium, but I’m more comfortable calling myself a “painter” than I am an “artist.” Painting is what I’ve devoted most of my time to, but in school I tried etching, screenprinting, and a little bit of performance and fashion. I used my time in the screenprinting class as an opportunity to try quilting, which I really enjoy and plan to continue with where time and resources allow. I’ll revisit performance if I ever grow out of my shyness.

Back to painting though, I arrived at oil painting as a result of my first encounter with a Kehinde Wiley work. It was a portrait of LL Cool J at the National Portrait Gallery in D.C. This was also in middle school, at the end of eighth grade. Prior to that I must’ve thought that “professional” fine art making had ended at the turn of the century. I had no knowledge of contemporary realist painters, and I had never seen a painting of a Black person that wasn’t depicted in a role of servitude. I decided immediately upon seeing that portrait that I aspired to match that scale and level of detail. I probably asked my mom, and she said no because of her apprehension about fumes in the house or something, but I was officially set on learning oil. I didn’t start actually using it until I went to college.

TA: I wouldn’t say that painting is my sole medium, but I’m more comfortable calling myself a “painter” than I am an “artist.” Painting is what I’ve devoted most of my time to, but in school I tried etching, screenprinting, and a little bit of performance and fashion. I used my time in the screenprinting class as an opportunity to try quilting, which I really enjoy and plan to continue with where time and resources allow. I’ll revisit performance if I ever grow out of my shyness.

Back to painting though, I arrived at oil painting as a result of my first encounter with a Kehinde Wiley work. It was a portrait of LL Cool J at the National Portrait Gallery in D.C. This was also in middle school, at the end of eighth grade. Prior to that I must’ve thought that “professional” fine art making had ended at the turn of the century. I had no knowledge of contemporary realist painters, and I had never seen a painting of a Black person that wasn’t depicted in a role of servitude. I decided immediately upon seeing that portrait that I aspired to match that scale and level of detail. I probably asked my mom, and she said no because of her apprehension about fumes in the house or something, but I was officially set on learning oil. I didn’t start actually using it until I went to college.

GT: How has your approach to painting changed over the years, if any? What have you learned?

TA: It might be that I’m too stubborn and stuck in my ways, but I always struggle to answer questions about the change and evolution of my practice. Some would call this a bad habit, but I generally start my paintings with some kind of vision or trajectory for the end result, and that includes the degree of finish that I’m looking for. I have all these works in progress, but I can’t stop prematurely because they’re simply not what they need to be yet. I paint slowly, so it has kept me in a place where it feels as though there's been no significant change in my approach. In critiques I would often get that the early stages of my paintings could be presented as completed works, that I should remove the burden of trying to match or replicate my reference images, but the initial layers of my paintings are never visually appealing to me. A lot of that probably goes back to this desire that I had to become a great realist when I was thirteen.

Personally, I don’t think that painting should come easily, and if I blow through something it usually means that it needs more attention. At the end of the day, painting is a skill that I’m still trying to learn and master. If I can turn the stubbornness thing around, I think I’ve learned that criticism needs to be taken in stride. I hardly forget the things that are said to me, so it’s not like I was going into critiques or meeting with professors and completely disregarding the advice that I received. I just feel like I can’t force anything out of myself, and the changes that I need to implement will only reveal themselves with consistent practice over time. It takes awhile for things to fully register, let alone become actualized, so I’m learning to trust myself and my process.

TA: It might be that I’m too stubborn and stuck in my ways, but I always struggle to answer questions about the change and evolution of my practice. Some would call this a bad habit, but I generally start my paintings with some kind of vision or trajectory for the end result, and that includes the degree of finish that I’m looking for. I have all these works in progress, but I can’t stop prematurely because they’re simply not what they need to be yet. I paint slowly, so it has kept me in a place where it feels as though there's been no significant change in my approach. In critiques I would often get that the early stages of my paintings could be presented as completed works, that I should remove the burden of trying to match or replicate my reference images, but the initial layers of my paintings are never visually appealing to me. A lot of that probably goes back to this desire that I had to become a great realist when I was thirteen.

Personally, I don’t think that painting should come easily, and if I blow through something it usually means that it needs more attention. At the end of the day, painting is a skill that I’m still trying to learn and master. If I can turn the stubbornness thing around, I think I’ve learned that criticism needs to be taken in stride. I hardly forget the things that are said to me, so it’s not like I was going into critiques or meeting with professors and completely disregarding the advice that I received. I just feel like I can’t force anything out of myself, and the changes that I need to implement will only reveal themselves with consistent practice over time. It takes awhile for things to fully register, let alone become actualized, so I’m learning to trust myself and my process.

GT: What underlying themes and ideas are you currently exploring in your practice?

TA: I typically lay them out as follows: afrofuturism, afropessimism, panafricanism, and ancestor veneration. I only very recently read Wilderson’s Afropessimism. I don’t know if I follow all of the tenets, but the theory makes perfect sense to me. I have a generally pessimistic outlook, and it has become the driving force behind the things I make. My disavowal of the here and now challenges me to try and create or imagine something else. For me, afrofuturism and panafricanism are about ideals. I think I gravitate more towards Martine Syms’ mundane-type afrofuturism, but it’s still about thinking and making a way forward, toward Black liberation. Ancestor veneration is what it is. One of the main things that keeps me going in times of mental hardship is the knowledge that I will never personally endure anything as traumatic as the Middle Passage or chattel slavery. I am gratefully indebted to my ancestors who did endure those traumas, and the fact of their endurance reminds me that I have the capacity and duty to persevere.

TA: I typically lay them out as follows: afrofuturism, afropessimism, panafricanism, and ancestor veneration. I only very recently read Wilderson’s Afropessimism. I don’t know if I follow all of the tenets, but the theory makes perfect sense to me. I have a generally pessimistic outlook, and it has become the driving force behind the things I make. My disavowal of the here and now challenges me to try and create or imagine something else. For me, afrofuturism and panafricanism are about ideals. I think I gravitate more towards Martine Syms’ mundane-type afrofuturism, but it’s still about thinking and making a way forward, toward Black liberation. Ancestor veneration is what it is. One of the main things that keeps me going in times of mental hardship is the knowledge that I will never personally endure anything as traumatic as the Middle Passage or chattel slavery. I am gratefully indebted to my ancestors who did endure those traumas, and the fact of their endurance reminds me that I have the capacity and duty to persevere.

GT: How do you find new ways to further explore those themes and expand your understanding of them?

TA: Reading, primarily. But I have so much reading to catch up on that making the work often feels irresponsible. I tell people that if I hadn’t gone to art school I’d have studied cultural anthropology, because it’s where my true interests lie. Cultural anthropology, socio-political theory, history, art history—There are so many people who have contributed to these fields of knowledge that it brings a level of self doubt if you’re just beginning and wanting to be in conversation. There's only 24 hours in the day, but I do try. I found it really challenging to stay on task in an academic setting. When I read books it has to be one at a time, scheduled, very formulaic, and not while I’m juggling a million other things at the same time. I spend a lot of time scrolling, but I don’t think of it in an entirely negative way. I think of social media as just another resource, and I use it to find articles, documentaries, and narratives that I wouldn’t necessarily find elsewhere. Lower success rate compared to an institutional database, maybe, it still takes me to interesting places that inform and develop my visual lexicon.

TA: Reading, primarily. But I have so much reading to catch up on that making the work often feels irresponsible. I tell people that if I hadn’t gone to art school I’d have studied cultural anthropology, because it’s where my true interests lie. Cultural anthropology, socio-political theory, history, art history—There are so many people who have contributed to these fields of knowledge that it brings a level of self doubt if you’re just beginning and wanting to be in conversation. There's only 24 hours in the day, but I do try. I found it really challenging to stay on task in an academic setting. When I read books it has to be one at a time, scheduled, very formulaic, and not while I’m juggling a million other things at the same time. I spend a lot of time scrolling, but I don’t think of it in an entirely negative way. I think of social media as just another resource, and I use it to find articles, documentaries, and narratives that I wouldn’t necessarily find elsewhere. Lower success rate compared to an institutional database, maybe, it still takes me to interesting places that inform and develop my visual lexicon.

GT: What sorts of feelings do you find yourself confronted with when in the midst of composing a composition and how do you feel afterwards?

TA: Sort of multidimensional. When I’m just starting, or even before I start, there’s a lot of the aforementioned urgency, and usually that morphs into a frustration with the very slow pace at which I work. I get aggravated with the fact that I haven’t been able to simplify my process or finish multiple paintings in a day as someone like Basquiat did, but I'm fully convinced that I’m making the work that I need to make, exactly as it needs to be made. Things could change in the future, but for now I deal with the tedious aspects of my practice by reminding myself that the Sistine Chapel wasn’t painted in a day. That’s not to compare myself to Michelangelo, but rather to say that my simple inability to speed things up is a simultaneous refusal of the fast-paced, hyperproductive culture that’s being pushed right now.

It’s very shortsighted, as far as my own financial capacity is concerned, but I’m not at all thinking of my paintings as products to be bought and sold. Aside from refusing to rush myself, I’m wary of what it would mean to pump out and sell paintings meant to honor and memorialize people who have fought and/or died for Black liberation struggles, or have simply been murdered for the color of their skin. When I talk about urgency, it’s coming from the fact that we’re losing people everyday, Sonya Massey, D’Vontaye Mitchell, and Samuel Sharpe being our latest examples. I can’t keep up, mentally or in my work. But the work is my way of trying to contend with the ceaseless brutality.

When I paint, I’m trying to think about the afterlife as a space where Black people are at eternal peace, free from persecution. I do it for my own sanity, because I really don’t see things changing to the extent that they need to, certainly not in my lifetime. I might not be able to have complete mental and physical security here, but I can imagine it for those who precede me in death. I don’t mean it to sound so ritualistic, but it is almost like building an altar, especially when I think about ancestor veneration as a major theme. In my eyes, the time spent on the paintings is a display of devotion, and I’m giving gratitude or paying respect in the most effective way that I know how.

Music is a big, constant thing in my life. I have headphones on all the time. Part of that is because I have bad misophonia, but music is a major coping mechanism in that it takes me out of the mundane and offers a distraction from my depressive tendencies. I also have an inner monologue going that hardly ever stops, so it’s usually a competition between that and the music. There are occasional moments where I'll have something like Fela Kuti or Toumani Diabaté playing on my headphones, and the inner monologue stops, which allows painting, embroidery, whatever I’m doing, to become a very meditative experience. I feel like the moments where I can create without thinking are the most profound, perhaps even adjacent to a spiritual experience. When that happens, it’s like I’m not even there.

TA: Sort of multidimensional. When I’m just starting, or even before I start, there’s a lot of the aforementioned urgency, and usually that morphs into a frustration with the very slow pace at which I work. I get aggravated with the fact that I haven’t been able to simplify my process or finish multiple paintings in a day as someone like Basquiat did, but I'm fully convinced that I’m making the work that I need to make, exactly as it needs to be made. Things could change in the future, but for now I deal with the tedious aspects of my practice by reminding myself that the Sistine Chapel wasn’t painted in a day. That’s not to compare myself to Michelangelo, but rather to say that my simple inability to speed things up is a simultaneous refusal of the fast-paced, hyperproductive culture that’s being pushed right now.

It’s very shortsighted, as far as my own financial capacity is concerned, but I’m not at all thinking of my paintings as products to be bought and sold. Aside from refusing to rush myself, I’m wary of what it would mean to pump out and sell paintings meant to honor and memorialize people who have fought and/or died for Black liberation struggles, or have simply been murdered for the color of their skin. When I talk about urgency, it’s coming from the fact that we’re losing people everyday, Sonya Massey, D’Vontaye Mitchell, and Samuel Sharpe being our latest examples. I can’t keep up, mentally or in my work. But the work is my way of trying to contend with the ceaseless brutality.

When I paint, I’m trying to think about the afterlife as a space where Black people are at eternal peace, free from persecution. I do it for my own sanity, because I really don’t see things changing to the extent that they need to, certainly not in my lifetime. I might not be able to have complete mental and physical security here, but I can imagine it for those who precede me in death. I don’t mean it to sound so ritualistic, but it is almost like building an altar, especially when I think about ancestor veneration as a major theme. In my eyes, the time spent on the paintings is a display of devotion, and I’m giving gratitude or paying respect in the most effective way that I know how.

Music is a big, constant thing in my life. I have headphones on all the time. Part of that is because I have bad misophonia, but music is a major coping mechanism in that it takes me out of the mundane and offers a distraction from my depressive tendencies. I also have an inner monologue going that hardly ever stops, so it’s usually a competition between that and the music. There are occasional moments where I'll have something like Fela Kuti or Toumani Diabaté playing on my headphones, and the inner monologue stops, which allows painting, embroidery, whatever I’m doing, to become a very meditative experience. I feel like the moments where I can create without thinking are the most profound, perhaps even adjacent to a spiritual experience. When that happens, it’s like I’m not even there.

GT: Thank you for sharing how intimate your process is. There is such a tender, supple, and confident way in which you wield your brush that creates a very realistic atmosphere in your paintings. Can you discuss your decision making? Whether that be deciding on the skin color of subjects to be this rich blue color or the locations they are in for example?

TA: I was using archival images in my work back in high school, but in my first year of college I had a professor who suggested that I might shift away from them in favor of doing portraits of contemporary figures. She even gave Stacey Abrams as an example. That was a no-go for me, but I did agree that the paintings needed something that would anchor them in the present. Neighborhood Watch and We Remember You are the foremost finished examples of paintings in which I gave full consideration to the background by depicting actual locations. I’m doing my best to omit scenes of explicit violence, and the locations do well to identify the particular events that I’m responding to. I’ve spent a lot of time pouring over these stories and have inadvertently memorized a number of scenes and images that are tied to various moments of tragedy.

With We Remember You, for example, I’m relying on my audience to be able to look at an image of Black Africans in front of a Tops Market and connect the dots to the race massacre that claimed the lives of ten people in 2022. Not to mention the ten sets of initials that appear on the canvas. If they can’t decode that, or if time passes and the shooting is obscured within the collective consciousness, then the painting becomes an invitation to research. If they don’t know or care to investigate, then the work isn’t for them.

The blue is interesting. Honestly, it’s just a visually arresting color, and I think that’s the main reason why I first started using it. It commands attention. I used to take walks every night on the lakefront, and it was shortly after the walks became a regular habit that I did my first blue painting. I’ve half-joked before that I may have received subconscious communications from Yemonja, and I do refer to Yoruba culture and color associations whenever I’m pressed to justify the choice. If you walk through the African section of the Art Institute of Chicago and read the labels on some of the Yoruba artifacts, there's mention of the color blue being used to signify peace and serenity and things like that. I’ve described the blue figures as “emissaries of the afterlife,” so they appear in our realm colored in blue to signify this difference between life and death that I’m imagining, perpetual struggle and perpetual tranquility, respectively.

GT: How do you find that archives and written histories help guide the direction of your compositions or comprehension of the work you make?

TA: The archive is essential. When I was first starting out, I’d simply find the archival images off of pinterest. The ethnographic, anthropological types. I still use pinterest on occasion, but it's usually when I can find links that take me to museum databases, large collections of field images, sometimes hundreds or thousands of files. As I think about panafricanism as a theme and an ideal, it’s important to me that I make these connections between the continent and the diaspora, no matter how forced or disparate they might seem. I’ve understood since middle school that the same forces that enable police to execute Black Americans without consequence are at work on the African continent, where Black labor and life is equally expendable. Anti-Black exploitation is the global order, from American prisons to Congolese mines. Even when you think about it from a historical perspective, colonization began the moment that the transatlantic slave trade ended. We change the words that we use to describe things to make it seem that there's been this massive upheaval in the ways that we think and act, but the material conditions are in many ways the same.

The role that Africa plays in the African American imagination is kind of fascinating. There’s this whole thing about the transatlantic slave trade being a massive rupture, and with that comes the desire to salvage lost histories and identities. I subscribe to the idea that, although we’re all black, “Black” is a unique identity that originated on the slave ships, basically to be compared to any other ethnic group. But I still want to think about what, or who, came before that. For me, imagining Africa is more about imagining a space where, though there are problems, there’s not the same kind of racialized hierarchy that exists in “the West.” Or, if there is, there’s a greater chance that it can be thoroughly toppled through collective efforts. It’s a space where ancestors roam alongside and are actively remembered by their living descendents. A professor once implied that it wasn’t really appropriate that I was combining all of these pictures of different African people without making any kind of distinction between them. I said that I don’t really have a problem with it because, as an African American, when you don’t know the specificities of your ancestry, you’re not left with much choice but to imagine that your ancestors could’ve been from anywhere on the continent. They could have looked like anyone in the colonial-era archives. I guess the work brings up interesting questions about time, past and present, change and continuity. The paintings are a time warp, and that has a lot to do with my perceptions of how we operate in relation to history. Some forget, ignore, and tell others to move on. The rest of us remember.

TA: I was using archival images in my work back in high school, but in my first year of college I had a professor who suggested that I might shift away from them in favor of doing portraits of contemporary figures. She even gave Stacey Abrams as an example. That was a no-go for me, but I did agree that the paintings needed something that would anchor them in the present. Neighborhood Watch and We Remember You are the foremost finished examples of paintings in which I gave full consideration to the background by depicting actual locations. I’m doing my best to omit scenes of explicit violence, and the locations do well to identify the particular events that I’m responding to. I’ve spent a lot of time pouring over these stories and have inadvertently memorized a number of scenes and images that are tied to various moments of tragedy.

With We Remember You, for example, I’m relying on my audience to be able to look at an image of Black Africans in front of a Tops Market and connect the dots to the race massacre that claimed the lives of ten people in 2022. Not to mention the ten sets of initials that appear on the canvas. If they can’t decode that, or if time passes and the shooting is obscured within the collective consciousness, then the painting becomes an invitation to research. If they don’t know or care to investigate, then the work isn’t for them.

The blue is interesting. Honestly, it’s just a visually arresting color, and I think that’s the main reason why I first started using it. It commands attention. I used to take walks every night on the lakefront, and it was shortly after the walks became a regular habit that I did my first blue painting. I’ve half-joked before that I may have received subconscious communications from Yemonja, and I do refer to Yoruba culture and color associations whenever I’m pressed to justify the choice. If you walk through the African section of the Art Institute of Chicago and read the labels on some of the Yoruba artifacts, there's mention of the color blue being used to signify peace and serenity and things like that. I’ve described the blue figures as “emissaries of the afterlife,” so they appear in our realm colored in blue to signify this difference between life and death that I’m imagining, perpetual struggle and perpetual tranquility, respectively.

GT: How do you find that archives and written histories help guide the direction of your compositions or comprehension of the work you make?

TA: The archive is essential. When I was first starting out, I’d simply find the archival images off of pinterest. The ethnographic, anthropological types. I still use pinterest on occasion, but it's usually when I can find links that take me to museum databases, large collections of field images, sometimes hundreds or thousands of files. As I think about panafricanism as a theme and an ideal, it’s important to me that I make these connections between the continent and the diaspora, no matter how forced or disparate they might seem. I’ve understood since middle school that the same forces that enable police to execute Black Americans without consequence are at work on the African continent, where Black labor and life is equally expendable. Anti-Black exploitation is the global order, from American prisons to Congolese mines. Even when you think about it from a historical perspective, colonization began the moment that the transatlantic slave trade ended. We change the words that we use to describe things to make it seem that there's been this massive upheaval in the ways that we think and act, but the material conditions are in many ways the same.

The role that Africa plays in the African American imagination is kind of fascinating. There’s this whole thing about the transatlantic slave trade being a massive rupture, and with that comes the desire to salvage lost histories and identities. I subscribe to the idea that, although we’re all black, “Black” is a unique identity that originated on the slave ships, basically to be compared to any other ethnic group. But I still want to think about what, or who, came before that. For me, imagining Africa is more about imagining a space where, though there are problems, there’s not the same kind of racialized hierarchy that exists in “the West.” Or, if there is, there’s a greater chance that it can be thoroughly toppled through collective efforts. It’s a space where ancestors roam alongside and are actively remembered by their living descendents. A professor once implied that it wasn’t really appropriate that I was combining all of these pictures of different African people without making any kind of distinction between them. I said that I don’t really have a problem with it because, as an African American, when you don’t know the specificities of your ancestry, you’re not left with much choice but to imagine that your ancestors could’ve been from anywhere on the continent. They could have looked like anyone in the colonial-era archives. I guess the work brings up interesting questions about time, past and present, change and continuity. The paintings are a time warp, and that has a lot to do with my perceptions of how we operate in relation to history. Some forget, ignore, and tell others to move on. The rest of us remember.

GT: Your subjects can be seen staring straight into the eyes of the viewer and they demand to be seen which I love so much. Do you have certain criteria in mind when bringing them to life?

TA: Gaze is so important, it’s one of the main things that I look for when selecting images to use. I want to generate a sort of confrontation between the figure and the viewer, and it’s all the more poignant when I can find an image in the depths of some archive that may have been otherwise forgotten. Other than that, I’m drawn to a varied complexity of gesture and pose, and I specifically think about the work done by Robert Farris Thompson in Aesthetic of the Cool, which outlined the relationships between African and African diaspora art forms. If I can find images from different cultures and juxtapose them in an interesting way, it makes for an interesting composition. Things never fall immediately into place; I usually collect and save images to be used later, and I’ve made changes to my collages when the paintings were well under way. So, while there is some level of criteria, a lot of it is up in the air.

GT: You are so adept in conveying this world in which the present and past meet and when I think of this, I think of your painting, Neighborhood Watch. Can you speak on this specific painting and your intentions?

TA: Neighborhood Watch was the work that I presented at my BFA exhibition last fall, and its description on my wall label read: “In memory of Trayvon Martin.” It’s interesting because Elizabeth Alexander’s book, The Trayvon Generation, came out a few months before I started and finished the painting, but I only learned of it the following year when it was assigned as a school-wide recommended read via the DEI office. They gave out free copies and later invited Alexander to speak at the end of the semester. Anyway, this was the first painting where I was unmistakably pairing the historical with the contemporary through an identifiable figure, which is Trayvon Martin at top center. I love his gaze and the middle finger, because that’s as confrontational as it gets in painting. I was ten when he was murdered, so it was slightly before middle school, but I had just gotten an iPod touch for Christmas a few months prior.

That gave me unrestricted access to the internet, which was new. Social media was a different level of exposure, different than a brief news segment in the morning or evening. I started putting things together and came to my own conclusions very quickly. Stayed up to date with the trial, finished the fifth grade, and was disgusted by the verdict. The title refers to George Zimmerman, the murderer who served as neighborhood watch captain and instigated the whole encounter. In my painting, though, the neighborhood watch is made up of three blue ancestor figures and an Igbo ikenga sculpture, and they’re there to guide and protect Trayvon in his transition from life into death. I like when a painting is not only confrontational, but somehow implicates the viewer in the scene. That was my main objective, to make the audience think about where they stand in relation to these near-constant deaths.

TA: Gaze is so important, it’s one of the main things that I look for when selecting images to use. I want to generate a sort of confrontation between the figure and the viewer, and it’s all the more poignant when I can find an image in the depths of some archive that may have been otherwise forgotten. Other than that, I’m drawn to a varied complexity of gesture and pose, and I specifically think about the work done by Robert Farris Thompson in Aesthetic of the Cool, which outlined the relationships between African and African diaspora art forms. If I can find images from different cultures and juxtapose them in an interesting way, it makes for an interesting composition. Things never fall immediately into place; I usually collect and save images to be used later, and I’ve made changes to my collages when the paintings were well under way. So, while there is some level of criteria, a lot of it is up in the air.

GT: You are so adept in conveying this world in which the present and past meet and when I think of this, I think of your painting, Neighborhood Watch. Can you speak on this specific painting and your intentions?

TA: Neighborhood Watch was the work that I presented at my BFA exhibition last fall, and its description on my wall label read: “In memory of Trayvon Martin.” It’s interesting because Elizabeth Alexander’s book, The Trayvon Generation, came out a few months before I started and finished the painting, but I only learned of it the following year when it was assigned as a school-wide recommended read via the DEI office. They gave out free copies and later invited Alexander to speak at the end of the semester. Anyway, this was the first painting where I was unmistakably pairing the historical with the contemporary through an identifiable figure, which is Trayvon Martin at top center. I love his gaze and the middle finger, because that’s as confrontational as it gets in painting. I was ten when he was murdered, so it was slightly before middle school, but I had just gotten an iPod touch for Christmas a few months prior.

That gave me unrestricted access to the internet, which was new. Social media was a different level of exposure, different than a brief news segment in the morning or evening. I started putting things together and came to my own conclusions very quickly. Stayed up to date with the trial, finished the fifth grade, and was disgusted by the verdict. The title refers to George Zimmerman, the murderer who served as neighborhood watch captain and instigated the whole encounter. In my painting, though, the neighborhood watch is made up of three blue ancestor figures and an Igbo ikenga sculpture, and they’re there to guide and protect Trayvon in his transition from life into death. I like when a painting is not only confrontational, but somehow implicates the viewer in the scene. That was my main objective, to make the audience think about where they stand in relation to these near-constant deaths.

GT: Who or what are some of your inspirations that you find yourself always circling back to?

TA: The list is virtually endless. Thinking of people with an art practice though, my foremost inspiration is Arthur Jafa, and I wrote my art history thesis on his work for that reason. He has revolutionized the way that I think about images, particularly through his early photo binders and the more recent video projects. He talks about a conversation with John Akomfrah who used the term “affective proximity” to describe the way that certain images or video clips are activated when placed side by side. It’s a really useful articulation of something that I often think about when making the collages that become my paintings and drawings.

I always end up questioning whether painting is the most effective, or affective, medium that I can use when I think about Jafa’s work; it’s opened up a realm of possibilities that I have yet to even fully think through. For people that wouldn’t be categorized as artists, there are so many historical and cultural figures that I won’t even try. I love African art: masks, masquerades, wood-carved figures. I am duly fascinated by the individuals that we’ve come to identify as martyrs: Malcolm X, Fred Hampton, Nat Turner, and Patrice Lumumba to name a few. Right now, I have a lot of admiration for Ibrahim Traoré. My studio is in East Garfield Park, and I’ve been here for a few months. I find inspiration in the scenes and people that I pass by on any given day. The psychological ease with which I move through the neighborhood, because it’s predominantly Black, is unlike anything I’ve ever experienced before.

GT: That is so wonderful, thank you for sharing. Can you walk us through what your journey of ideation and process typically looks like? How long does it take for you to finish a painting? How do you know when a painting is finished?

TA: All of the paintings begin as collages that I make on my iPad, using Procreate. I just throw pictures together, erase things, move things around until it feels right, or at least right enough to start. As I mentioned earlier, sometimes the composition will change well after I’ve started. I’ve got hundreds of years and counting worth of grievances to consider so there’s never any shortage of material, and I’m not working on any particular timeline. Larger paintings, talking around five feet in either direction, can take upwards of three months of focused work, meaning I’m not bouncing between projects. That’s usually never the case, so things typically take six months to a year. It’s actually crazy when I think about it. A painting is technically finished when I feel that there's more risk than reward involved in continuing. I have to think about the hours that I’ve put in up until that point and whether or not I’d be willing to ruin it by changing something that might end up looking worse, or not that different. My final finish line, the most challenging thing, is deciding on a title.

TA: The list is virtually endless. Thinking of people with an art practice though, my foremost inspiration is Arthur Jafa, and I wrote my art history thesis on his work for that reason. He has revolutionized the way that I think about images, particularly through his early photo binders and the more recent video projects. He talks about a conversation with John Akomfrah who used the term “affective proximity” to describe the way that certain images or video clips are activated when placed side by side. It’s a really useful articulation of something that I often think about when making the collages that become my paintings and drawings.

I always end up questioning whether painting is the most effective, or affective, medium that I can use when I think about Jafa’s work; it’s opened up a realm of possibilities that I have yet to even fully think through. For people that wouldn’t be categorized as artists, there are so many historical and cultural figures that I won’t even try. I love African art: masks, masquerades, wood-carved figures. I am duly fascinated by the individuals that we’ve come to identify as martyrs: Malcolm X, Fred Hampton, Nat Turner, and Patrice Lumumba to name a few. Right now, I have a lot of admiration for Ibrahim Traoré. My studio is in East Garfield Park, and I’ve been here for a few months. I find inspiration in the scenes and people that I pass by on any given day. The psychological ease with which I move through the neighborhood, because it’s predominantly Black, is unlike anything I’ve ever experienced before.

GT: That is so wonderful, thank you for sharing. Can you walk us through what your journey of ideation and process typically looks like? How long does it take for you to finish a painting? How do you know when a painting is finished?

TA: All of the paintings begin as collages that I make on my iPad, using Procreate. I just throw pictures together, erase things, move things around until it feels right, or at least right enough to start. As I mentioned earlier, sometimes the composition will change well after I’ve started. I’ve got hundreds of years and counting worth of grievances to consider so there’s never any shortage of material, and I’m not working on any particular timeline. Larger paintings, talking around five feet in either direction, can take upwards of three months of focused work, meaning I’m not bouncing between projects. That’s usually never the case, so things typically take six months to a year. It’s actually crazy when I think about it. A painting is technically finished when I feel that there's more risk than reward involved in continuing. I have to think about the hours that I’ve put in up until that point and whether or not I’d be willing to ruin it by changing something that might end up looking worse, or not that different. My final finish line, the most challenging thing, is deciding on a title.

GT: What are some goals or hopes you hold for the near future? This can be art-focused or beyond.

TA: Until very recently I was dead set on going to graduate school for an MFA, and having it happen as soon as possible. In light of current events, namely the genocide in Gaza, I’m dealing with a level of disillusionment that I’ve never experienced before. Part of that has been reevaluating what higher education means to me, and examining the role that it can and often does play in generating complicity. My goals have shifted dramatically over the last ten months, so much so that I don’t really know what my goals are right now. I’m not bothered by it. My main goal, apart from finishing all of this work that I’ve started, is to start breaking out of my shell here in East Garfield Park. To be in community with other Black people.

GT: This has been lovely, Taylor. Thank you for your time!

TA: Absolutley. Thank you!

TA: Until very recently I was dead set on going to graduate school for an MFA, and having it happen as soon as possible. In light of current events, namely the genocide in Gaza, I’m dealing with a level of disillusionment that I’ve never experienced before. Part of that has been reevaluating what higher education means to me, and examining the role that it can and often does play in generating complicity. My goals have shifted dramatically over the last ten months, so much so that I don’t really know what my goals are right now. I’m not bothered by it. My main goal, apart from finishing all of this work that I’ve started, is to start breaking out of my shell here in East Garfield Park. To be in community with other Black people.

GT: This has been lovely, Taylor. Thank you for your time!

TA: Absolutley. Thank you!